A race is on in the Colorado Plateau, where native and nonnative plants are battling to out-compete the other and lay claim to the land. In this dynamic location bridging Utah, Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico, the situation is heating up.

It’s a race scientists are not willing to gamble on. Andrea Kramer, Ph.D., a conservation scientist at the Chicago Botanic Garden, is working with a research team to determine how to give native plants the lead.

Since invasive species such as cheatgrass arrived on the Plateau more than a century ago, they have fueled destructive fires and caused numerous other problems, according to Dr. Kramer.

These problems do not deter the expansion of cheatgrass, but they do inhibit many native species. This clears the way for more cheatgrass to grow each year. In this area that is home to numerous native animals including the nearly endangered sage grouse bird, a solution is imperative.

The cheatgrass invasion is an accelerating problem that once seemed hopeless. But now, building on research begun in the Garden’s Plant Production Greenhouse by Becky Barak, currently a Ph.D. student in the Garden’s joint graduate program in plant biology and conservation with Northwestern University, Kramer and her team have learned that native species are not as helpless as they once seemed. Some of them may even be unlikely heroes.

“We’re focusing on the native wildflowers, particularly on the Colorado Plateau because they are so important to the functioning of those natural communities, and because so little is known about them,” said Dr. Kramer.

She has worked with botanists around the Colorado Plateau to identify specific species of native plants, categorized as native “winners,” that have naturally begun adapting to the new circumstances.

Unlike their counterparts in unaltered locations, these species have learned how to grow their roots deeper, faster to access water, or found other ways to gain an advantage. Not only are they capable of surviving in an unnaturally harsh environment, but Kramer believes they could prove to be smart and fast enough to help keep invasive species in check.

In labs at the Garden, she is working with graduate student Alicia Foxx to stage trials between cheatgrass and these plants in conditions nearly identical to those in the Plateau. Kramer’s goal is to identify the strongest native “winners.” Once they are known, she will work with local partners in the west to test the best seeds on the ground in this struggling landscape. Then, they will make sure the seed is available for restoration work — positioning the native “winners” for success.

“Ultimately, we want to get the right seed in the hands of the right people,” said Kramer.

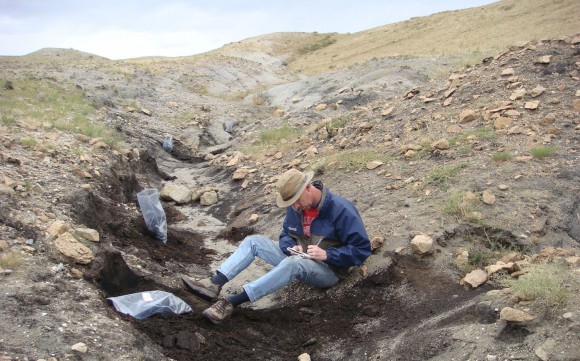

Kramer’s field research began last year, and will resume in coming weeks. On a typical expedition, she flies into the Las Vegas airport — the closest access point to the Plateau. Along with fellow Garden researchers and graduate students, she climbs into a research vehicle and rolls into the field armed with data from the lab, a bundle of tools, and camping equipment. Over a series of days at a range of locations, they meet with local botanists and collect seeds from key locations to take back to the Garden lab for study.

This year, they are eager to return to a site they planted with native “winners” last year, in order to check for progress. The site, called Pine Ridge, experienced an extensive fire in July 2012 when lightning struck an area with abundant cheatgrass.

When compared to lab results, their findings will inform which seeds may go into development for restoration use on the Plateau.

The concept of native “winners” is helpful to many newer research projects in other locations, including Illinois. Another graduate student in the Garden’s program is beginning to apply the process to plants found in Illinois wetlands.

It is this opportunity for collaboration and expansion that most excites Kramer. “It’s a great project because it uses the expertise of many garden research staff members and engages students,” she noted. “We have this in-house expertise in working with the species, the labs here are unique, and the opportunity to engage students is also unique.”

Learn more about Dr. Kramer’s work and watch a video interview.

Kramer spent her youth exploring an agricultural area of Nebraska where she grew up. Her love of the outdoors led her to study botany in Minnesota, where she quickly became enamored with prairie plants. At the Garden, she takes every opportunity to stroll the Dixon Prairie. “It’s like revisiting old friends,” she said.

Clearly, Kramer is a good friend to have.

©2013 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org