There is a Native American myth that is believed to have originated with the Onondaga tribe of the Iroquois nation of northeastern North America. It is a creation legend about how the earth (the land) was created. The legend incorporates a number of different animals including swans, pied-billed grebes, muskrats, and many others. The central character in the story is a turtle. The turtle, an island in a world of water, was chosen to carry soil and tree seedlings on its back, which eventually became the land the people lived on. So this story is about preservation and nurturing. Although this legend may have originated with the Onondaga, it is a common myth found throughout many Native American cultures.

The fact that the turtle myth was so widespread across the continent is not really all that surprising when you consider how many different species of turtles there are. There is a turtle species for just about every kind of wetland environment that exists, from sea turtles to bog turtles to river cooters and pond sliders. There are approximately 17 species of turtles native to Illinois and nearly half of those occur at the Garden.

Other than birds, turtles are among the most common animals you are likely to encounter on any given day during the growing season at the Garden. Like the early blooming wildflowers in McDonald Woods, turtles are truly one of the first signs of spring. Soon after the ice melts on our lakes, turtles begin moving from the bottom of the lakes where they spent the winter hibernating. During the dark days of winter under the ice, turtles are able to slow their bodily functions down to the point where they can obtain enough oxygen to survive by absorbing it through the mucus membranes and tiny capillaries of their throat and cloaca (the common opening for defecation and egg laying). They also use some fascinating chemistry, part of which involves dissolving calcium from their shells to help neutralize toxic acids that would be fatal under normal circumstances. Still cold and sluggish from their long winter sleep, they begin swimming around near the surface, often poking their heads out to take their first real breath of air since descending to the bottom of the lakes in fall.

Several years ago, I initiated a turtle project with one of the summer interns. We set out to try to determine how many turtles and how many species occur in our lakes. Utilizing a number of different live traps, we were able to count most of the individuals and almost all of the species that can be found here. Over three months, we were able to capture nearly eighty individuals of eight different species.

The turtles can be divided into two general groups, those that like to bask (sun themselves on logs, rocks, or on the shore) and those that rarely bask. The basking turtles are the species most often encountered at the Garden. The most abundant member of this group is the red-eared slider.

This is the turtle of dime-store fame. There was a time when it seemed like every kid had one of these sliders as a pet – do you remember Cuff and Link from the movie Rocky? They are distinctive, with a bright red slash along the side of their heads. Although they are the most abundant species here, they are not native to this part of Illinois. Sliders have been introduced to many parts of the country where they had not previously been found. This is the result of all those dime-store turtles that grew up to be bigger turtles that were eventually released when their owners either ran out of room for them or the appeal of these long-lived animals wore off. Like many introduced species, the slider is aggressive toward our native species and as a result has achieved a dominant place in the turtle population.

The slider is not the only introduced turtle at the Garden. Some other species that can be found here that were not known in the region historically include the three-toed box turtle, the false map, common map, and the Ouachita map turtles.

Releasing pet turtles is not a good idea. The slider has greatly changed the dynamics of natural turtle populations all over the country. Some species, like the box turtles, which are terrestrial species that do not hibernate in lakes, are sometimes found at the Garden only after they have died after not being able to survive the winter here. There is also the possibility of spreading diseases.

The native turtles found at the Garden include the Midland painted turtle, Western painted turtle, stinkpot or musk turtle, spiny soft-shelled turtle, and the snapping turtle. The stinkpot and the snapping turtles are members of that group of more aquatic turtles that do not typically bask on logs or rocks. So although the snapping turtle is a common species at the Garden, it and the stinkpot are not seen nearly as much as the basking species.

Where do these turtles get their names? The map turtle gets its name from the pattern along the underside of the shell and along its neck and head that looks like topographic lines on a map. The box turtle has a hinged plastron (belly) that allows it to pull its head and legs inside the shell and close the “doors” sealing out predators.

Soft-shell turtles have a soft, leathery shell that bends and flexes like an old leather baseball mitt. They have a very low profile and look like a large, olive-colored drab Frisbee when they are basking on the lawn. Painted turtles often have attractive red markings along the edge of their carapace (shell) and plastron. As far as the stinkpot turtle goes, I’ll let you guess why they have that common name. I’m sure that if you do some digging, you’ll be able to sniff out the answer.

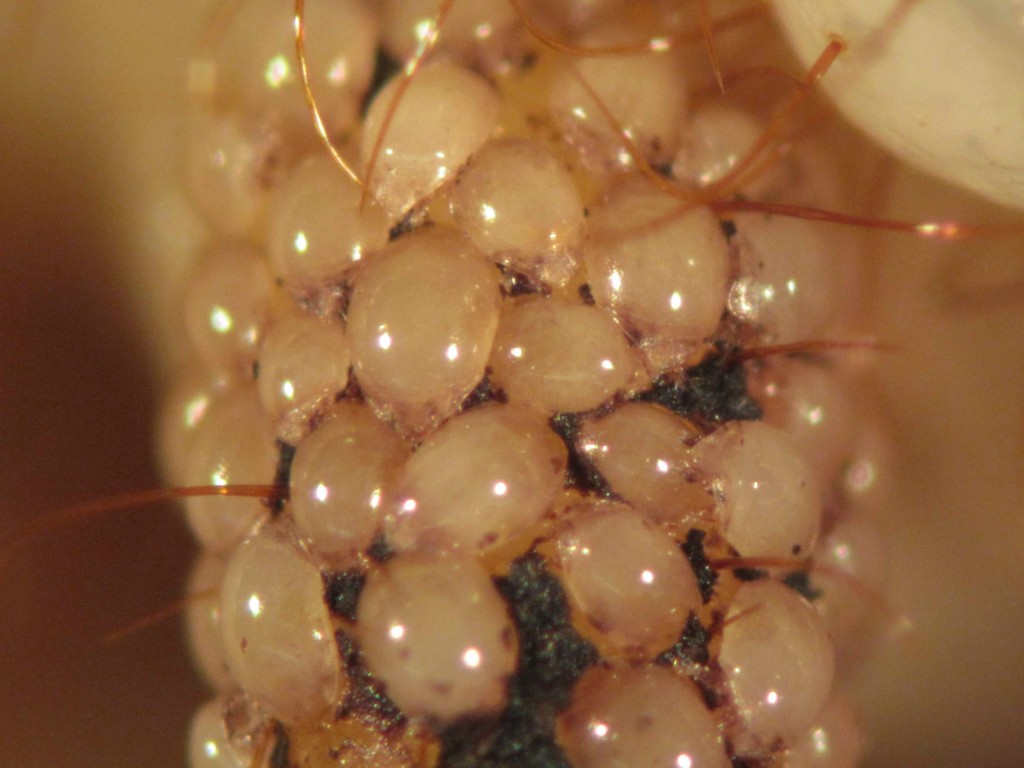

The turtles are egg-laying reptiles. Their eggs are probably best described as leathery-shelled ping-pong balls. During the summer, the adult turtles will haul themselves out along the shore and look for suitable places to dig a hole in which to deposit their eggs. At the Garden, turtles often choose to lay their eggs in the mulch around the tree and shrub planting beds, probably because it is a softer, easier place to dig. This egg-laying season is a dangerous time for turtles.

During this time they are out of the water, many encounter predators, and often cross roads looking for

nesting locations. Once the eggs are laid, the turtle covers the eggs with soil and then retreats to the water, leaving the eggs and young to fend for themselves. Usually the eggs will hatch in 45-90 days, but sometimes, for individuals that lay their eggs too late in the season, they may overwinter. Although turtles generally lay a good number of eggs (2-40 or more, depending on the size of the individual and species), the failure of those eggs is high due to predators. Skunks and raccoons are probably the two most frequent predators of turtle eggs, but almost any predator that comes across a nest is likely to take at least some.

What do these critters eat? Most species are omnivores. They eat a combination of plant and animal material. The common map turtle specializes in mollusks, like clams and snails that it crushes with its broad hard mouthparts. The spiny soft-shell is a fast swimmer and often feeds on fish. The red-eared slider is also omnivorous, but tends to become more of an herbivore as it gets older. It should also be noted that turtles perform a valuable ecosystem service as carrion feeders by feeding on dead fish and aquatic animals that would otherwise remain for long periods as they decompose. So you can think of turtles as sort of turkey vultures of the aquatic world – the sanitation squad.

Visitors frequently encounter turtles crossing the road at the Garden during the summer. Although the urge is strong to help the turtle back into the lake, don’t approach them too closely since turtle are very good at defending themselves and have long necks that can dart out and grab anyone or anything that gets too close. Turtles have very sharp-edged mouthparts and once they get hold of something, they don’t let go. Many a dog has lost a piece of its nose when getting too inquisitive about turtles.

If you happen to be visiting the Garden in summer and spot a turtle basking in the sun, try to see if you can figure out which species it is. Perhaps more importantly, if you spot a turtle, try to remember the Onondaga legend and the great responsibility bestowed on it to preserve the land and plants for the people.

©2013 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org