This summer, the Chicago Botanic Garden is transforming—with tall coconut palm trees and other iconic plants of Brazil, inspired by the designs of renowned Brazilian landscape designer Roberto Burle Marx.

The making of Brazil in the Garden started with an unlikely source, a family’s brick townhouse in Philadelphia.

Two members of the Garden’s design team visited the townhouse last summer, not sure what to expect. What they found was a treasure trove of original work by Burle Marx (1909–94), including stacks of rare, numbered lithographs, rolled tapestries too large to hang, and framed paintings. Some of the pieces, which had never been on public display, are now part of an exclusive Burle Marx exhibition at the Garden.

The collection had been in private hands, owned by landscape architect Conrad Hamerman and kept on the third story of his townhouse. When Hamerman died in 2014, his family inherited the pieces. Hamerman was a close friend of Burle Marx, and represented his work in the United States; Burle Marx gave him the pieces as gifts and as payment for his services.

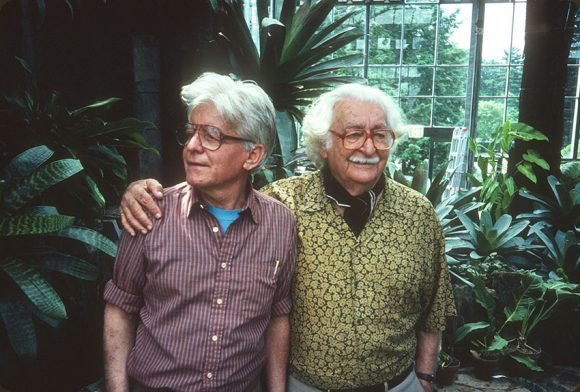

Photo ©Rick Darke

Through a contact, the Garden’s exhibition manager Gabriel Hutchison and senior designer Nancy Snyder met with Hamerman’s wife and daughter in Philadelphia to discuss Burle Marx’s artistic legacy and his friendship with Conrad Hamerman. The Garden’s Burle Marx exhibition reveals a rare glimpse of Burle Marx as an artist known for his bold colors, abstract shapes, and modernist style.

Hutchison and Snyder spent two days reviewing and evaluating the material for possible exhibition. “The collection was so much more diverse than I had imagined—sketches, oil paintings, landscape plans, and painted canvas wall hangings,” Snyder said. “This was really an honor to work on, and all along it felt like exhibiting the work was a suitable tribute to the rich friendship between the Hamermans and Roberto Burle Marx.”

Hamerman and Burle Marx met as young men in Brazil. Hamerman was a landscape designer who wanted to become an artist, and Burle Marx was an artist who wanted to become a landscape designer. Above all, they were both avid plant people. Their mutual love of plants, art, and design formed the basis of a lasting friendship that inspired them to travel on many expeditions to collect plants together.

“Conrad was a professional colleague of Roberto’s and collaborated with him a lot,” said Hutchison. “Over the years they became close friends, and although Conrad enjoyed doing his own work, I think he was most passionate about working with Roberto.”

The two even taught university courses together, which is where landscape architect Andrew Durham first encountered Burle Marx’s work. A former student and family friend of Hamerman’s, Durham arranged the loan of pieces from the family’s personal collection for the Garden’s exhibition.

“One thing that made Hamerman unique as a professor was his close friendship with Roberto Burle Marx,” said Durham. “Our class traveled for a month to Brazil, where Burle Marx personally showed us his gardens. That trip changed many of us forever, and I’ve embedded in my own work much of what I learned from Burle Marx’s use of texture and color.”

Though known for revolutionizing tropical landscape design, Burle Marx also worked in other artistic mediums. The paintings and textiles at the Garden exhibition showcase his style of vast swaths of bold hues, cubist influences, and contrasting fabrics.

See the Roberto Burle Marx exhibition, open 9 a.m. to 7 p.m. in the Regenstein Center, Joutras Gallery, through September 10, 2017.

Throughout the Garden, we’re paying tribute to the vibrant spirit of Brazil. Look for samba on the Esplanade, the Brazilian national cocktail in the Garden View Café, cool plants including striking Bismarck palms, and much more. See Brazil in the Garden—throughout the Garden—through October 15, 2017.

Throughout the Garden, we’re paying tribute to the vibrant spirit of Brazil. Look for samba on the Esplanade, the Brazilian national cocktail in the Garden View Café, cool plants including striking Bismarck palms, and much more. See Brazil in the Garden—throughout the Garden—through October 15, 2017.

©2017 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org