While checking the perimeter fence around McDonald Woods to see if there was any damage to the fence after a windy day, I discovered a large red oak that had lost its foothold in the frozen soil and had toppled over against a white oak. Since the tree was threatening to push the other oak over into the fence, I decided to cut the red oak down to save the white oak and the fence.

When trying to remove a leaning tree, you have to start at the base and work your way to the top as each section falls away. The base of the tree was good and solid, sending a shower of sour-smelling oak shavings flying from the chainsaw. When I got about halfway up the trunk, the saw began spewing dark brown flakes of rotting wood, and the sawing became easier. After a few more cuts, the trunk became mostly hollow and the top of the tree crashed to the ground.

Looking back at one of the middle sections of trunk, where the center was a rich dark brown from the rotting wood, I noticed a thick, white object shaped like the letter “C”.

A closer look showed the object to be a large grub from a beetle. These grubs are similar to the white grubs of Junebugs and Japanese beetles that you find in your gardens and lawns, but much larger. Although the rotten wood was frozen, I was able to split open the log, revealing a whole colony of 30 to 40 beetle grubs about 2 inches long and about a half inch in diameter. Each grub was cradled in a smooth-surfaced cell in the rotted wood. Even at temperatures well bellow freezing, the grubs were able to move enough to show they were alive.

As it turned out, these grubs were the larvae of one of our largest woodland beetles, known as the stag beetle or stag-horn beetle. These beetles are one of the myriad invertebrates active year-round, doing the important work of reducing fallen trees to rich organic soil that will help other trees grow and support the next generation of plants.

These beetles are members of the Coleoptera (beetles) and get their name from the large antlerlike mandibles (jaws) found on the front of the head of the males. The females also have mandibles, but they not as impressive as those of the males. The large mandibles are used for territorial defense and also to protect the beetles from any birds or other animals that might try to eat them. The impressive “antlers” can look threatening to people when they first encounter them; however, they are not a serious threat to people and will only give you a pinch if you handle them roughly. It is not uncommon to find the large brown stag beetles around buildings near woodlands at night, when they are sometimes attracted to the lights.

These critters are fascinating, not only because they are social in the larval stage and can take several years to mature, but they can also produce an assortment of sounds that are thought to help with communication between the grubs. The grubs have a striated structure on the leg that allows them to produce sound (called stridulation), kind of like rubbing a spoon on a washboard. If you notice the dark-colored segment that looks distended on the end of the grub, it is the digestive chamber, where the wood the grub consumes is digested with the aid of microorganisms. If you give one of these guys a gentle squeeze, you will notice a stream of liquified, dark brown wood coming from the tail-end of the critter.

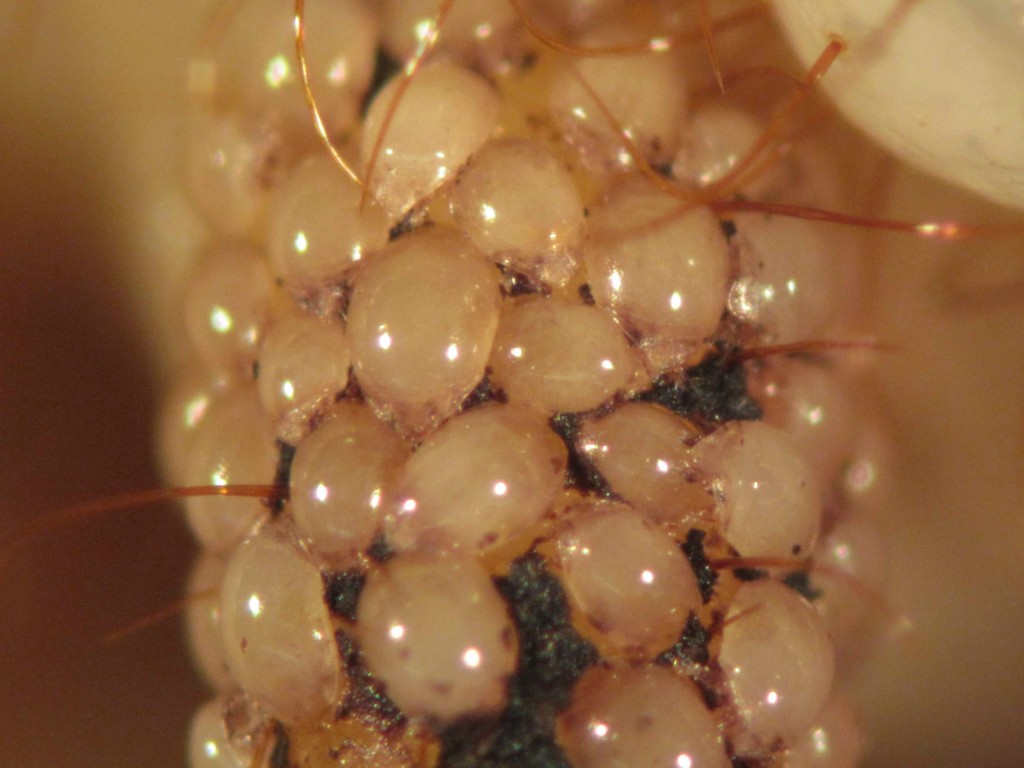

One last item of interest about these wood-grubbing dynamos is that they often carry a large population of mites around, clinging to their bodies. When I took a closer look at the grubs, I found dozens of whitish-colored tiny mites attached to each of their legs.

This observation lead me to recall the verse by the Victorian mathematician, Augustus De Morgan:

- Great fleas have little fleas upon their backs to bite ’em,

- And little fleas have lesser fleas, and so ad infinitum.

- And the great fleas themselves, in turn, have greater fleas to go on,

- While these again have greater still, and greater still, and so on.

These mites do neither the beetles nor the grubs any harm; they are just along for the ride and probably snacking on any choice fecal pellets deposited by the beetles. If you find yourself sitting on a log out in the woods, you just might be perched above a nest of developing stag beetles.

©2013 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org