Peter DeJongh is a first-year master’s student studying land management and conservation in the graduate program at Northwestern University and the Chicago Botanic Garden. His academic focus is on developing strategies to optimize plant and wildlife conservation and restoration. He aims to work in applied conservation or environmental consulting upon completion of his degree.

Peter DeJongh is a first-year master’s student studying land management and conservation in the graduate program at Northwestern University and the Chicago Botanic Garden. His academic focus is on developing strategies to optimize plant and wildlife conservation and restoration. He aims to work in applied conservation or environmental consulting upon completion of his degree.

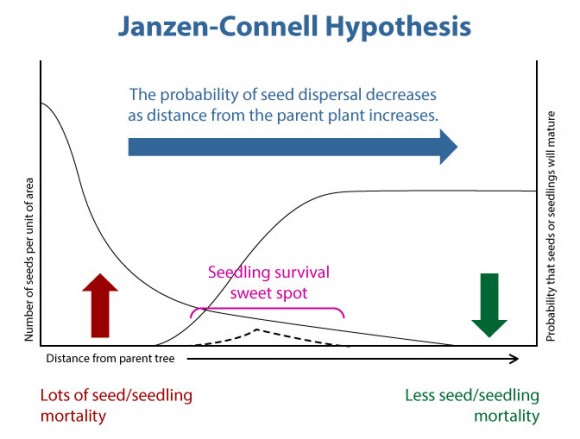

Imagine a large, beautiful canopy tree standing in the middle of a lush, tropical rainforest. This centuries-old tree produces thousands of seeds every year that densely litter the forest floor around it. Where then would you imagine its seedlings are likely to spring up? Probably in the seed-covered area around the tree right? Well, according to the Janzen-Connell model, you’d be wrong.

Daniel Janzen and Joseph Connell are two ecologists who first described this phenomenon in the early 1970s. They put their exceptional minds to the task and independently discovered that the probability of growing a healthy seedling was actually lower in the areas with the most seed fall. They hypothesized that seed predators and pathogens had discovered the seed feast around the parent tree and moved in, preventing any seeds in the area from growing into seedlings. These predator pests include beetles, bacteria, viruses, and fungi, and have been labelled as host-specific predators and pathogens since they appear specifically around the parent tree, or host.

Janzen and Connell’s hypothesis shows just how important the animals that eat the seeds are to the parent tree. These primates, birds, and other vertebrates move the seeds to different areas where they can successfully grow without being bothered by those pesky host-specific predators. Without these animal helpers, the forest couldn’t continue to grow, and the world’s most diverse areas would be in serious trouble.

Garden post-grads and scientists are in the field working on restoration efforts in the Colorado plateau, fossil hunting in Mongolia, and filming videos on sphinx moths. Interested in our graduate programs? Join us.

Students in the Chicago Botanic Garden and Northwestern University Program in Plant Biology and Conservation were given a challenge: Write a short, clear explanation of a scientific concept that can be easily understood by non-scientists. This is our fifth installment of their exploration.

©2016 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org