Do you ever feel like trying to understand plant science research can be as daunting as deciphering a passage written in a foreign language?

As a budding plant scientist in the joint Chicago Botanic Garden/Northwestern University Ph.D. program, I find it exciting to pick through dense scientific text. Uncovering the meaning of a new acronym and learning new vocabulary can be thrilling, especially when decoding something new.

But the commonly used styles in scientific writing and presentation packed with language used to convey big topics in small spaces can be really off-putting to an audience of non-scientists. Many of us can conjure up a memory of a professor or teacher who seemed to like their subject matter but couldn’t convey the material in an interesting way. All of a sudden, science became boring.

Rather than struggling to learn this “foreign language,” many folks stop paying attention. Lack of scientific literacy, especially as it applies to plants, is a pity. Plants are all around us! They are so valuable to the entire planet. The very applicable field of botany shouldn’t be something that’s only discussed and understood in laboratories or scientific conferences—it should be for everyone.

This idea inspires me to try and bring my current botany research to a wide variety of people.

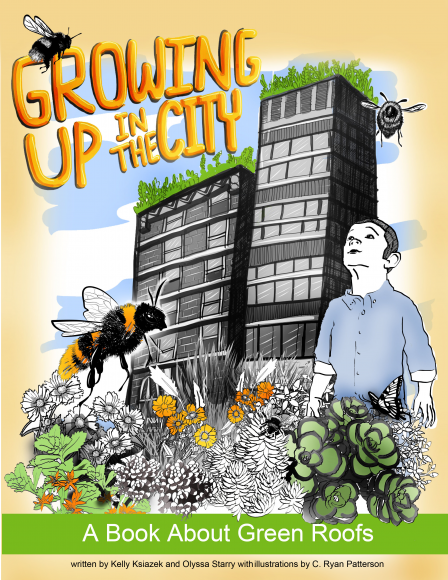

For example, I recently realized that there are very few resources available to teach young students about the habitat where I currently collect most of my data: green roofs. While some of the methods I use for data collection and analysis can be quite complex, the motivations behind my work and some of the findings can be broken down into some basic ideas, applicable to students of all ages. So a fellow botanist and I wrote and produced Growing Up in the City: A Book About Green Roofs.

Our children’s activity book teaches youngsters about some of our research findings. The book follows a pair of native bumblebees through a city, where they guide the reader through engaging activities about the structure, environmental benefits, and motivations for building green roofs. At the end, readers even have the opportunity to ask their own research question and carry out a green roof research project of their own.

Interested in your own copy of our book? More information and a free digital download of the book are available at greeningupthecity.com.

The activity book is just one example of ways that plant scientists can engage with a broader audience and make their research findings more accessible. Some of the other activities that my colleagues here at the Chicago Botanic Garden and I have participated in include mentoring undergraduate and high school students, speaking to community organizations, creating lessons for schools and school groups, volunteering for summer programs, and maintaining a presence on the Internet through online mentoring, blogging, websites, and Twitter.

Here at the Garden, we scientists also have a unique variety of opportunities to share our science with the thousands of visitors who come to the beautiful Daniel F. and Ada L. Rice Plant Conservation Science Center. If you’ve never been to the Plant Science Center, you should definitely stop by the next time you’re at the Garden. You can see inside the laboratories where the other scientists and I collect some of our data. There are also a lot of interactive displays that aim to demystify plant science research and decode some of the “foreign language” that science speak can be. For a really interactive experience, come visit us on World Environment Day, Saturday, June 6, and talk to scientists directly. Bring your kids, bring your neighbors, and ask a botanist all those burning plant questions you have! We promise to only speak as much “science” as you want.

For more information about my research and science communication efforts, please visit my research blog, Kelly Ksiazek’s Botany in Action, and follow me on Twitter @GreenCityGal.

©2015 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org