I am an enthusiast of space design.

After a two-year technical degree at École Boulle (a school of fine arts and crafts and applied arts in Paris, France), I decided to study for my master’s degree at the National School of Landscape Architecture of Versailles.

For me, work in landscape architecture is the best way to unite many different and interesting fields, such as art, sociology, and ecology. Designing spaces where people will live and have an emotional connection to their surroundings is my way of creating happiness.

I chose to do an internship in the United States to broaden my understanding of how cities here developed over time in comparison with France, which has had many hundreds of years to develop. In Chicago, I saw that the gardens were designed like the links of the city, and learned one of the reasons for this is Chicago’s motto, Urbs in horto, which means “city in a garden.”

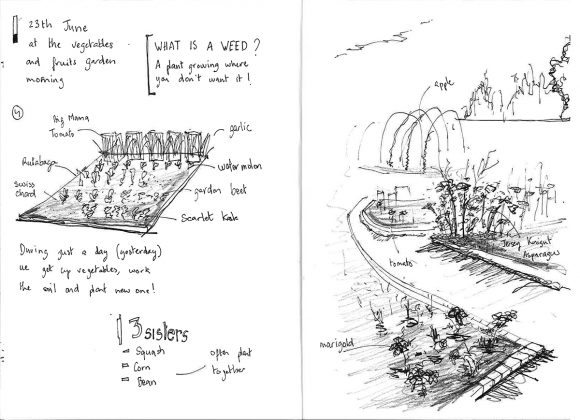

Through my internship at the Chicago Botanic Garden, I also wanted to learn practical horticulture skills, like plant identification, choosing the right plants for certain spaces, and techniques for good plant health. For example, to improve air circulation and the growth of some vegetables, I learned to stake up tomatillos, and use trellises for beans.

I spent a total of four weeks at the Chicago Botanic Garden, working mainly in the Regenstein Fruit & Vegetable Garden under that garden’s horticulturist, Lisa Hilgenberg. During Pepper Sundays, I learned that one of the special plants in the Fruit & Vegetable Garden is the bull-nose pepper—a favorite of Thomas Jefferson, who was an ambassador to France and a great plant enthusiast. He made many plant exchanges with people around the world, especially France. It goes to show that plants everywhere bring people together, no matter the country or culture.

Gardens are always changing, so there were always new things to see and learn each day—not just with the plants, but also with understanding how people use the gardens at the Chicago Botanic Garden.

Visitors come to learn about plants, to enjoy their day in a beautiful place, and to be inspired. I saw how important green spaces are to people. My internship has encouraged me to share knowledge with the visitors, the interns, the staff, and volunteers. It is a true collaboration and exchange between people. For example, when I worked in the nursery, the staff and the interns showed me the breadth of the production and how the Garden is constantly trying to help people experience the Garden in a new way.

For me, the Chicago Botanic Garden, in addition to being a beautiful garden, is an amazing, open-air encyclopedia of plants and garden design, as well as a wonderful space for public enjoyment.

I am grateful to the French Heritage Society, which partners with the Garden on a collaborative internship exchange, to the Ragdale Foundation, which has hosted me, and to the Chicago Botanic Garden and Lisa Hilgenberg for giving me this extraordinary opportunity. And finally, I hope that this will be the beginning of new friendships for me.

This is the fifth year of our wonderful intern exchange with the French Heritage Society. As Lisa Ho spent her summer in Chicago, Chicago Botanic Garden employee Eileen Brucato went over to France to gain experience in three chateau gardens: Château de Brécy, Château d’Acquigny in Normandy, and Château de la Bourdaisière in Tours.

©2016 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org