On an early spring day in the offices of the Regenstein Fruit & Vegetable Garden, Lisa Hilgenberg, Garden horticulturist, is seated at a rustic conference table sorting through pencil drawings of garden beds and photos of vegetable plants. Across the Garden, in the Garden View Café kitchen, chef Peter Pettorossi is considering a cabbage slaw recipe inspired by those same plants.

The concept of serving fresh, seasonal, local food at the Garden was key to café renovations completed one year ago. Produce and fruit from the garden, as well as from Windy City Harvest plots in the area, and other local vendors, is increasingly available in many dishes including salads, calzones, daily soups, and other specials.

Although the café and the Fruit & Vegetable Garden are physically separate, they come together in the growing season through an intricate network of connections that bring garden to table.

“It’s such a unique opportunity,” said Harriet Resnick, vice president of visitor experience and business development. “It opens people’s eyes to what we offer here.” New signage in the garden indicates which plants are on their way to the café. It also feels right, she explained. “If you are a true gardener, that’s how you live your life—by the plants of the season.” She added that the café has only grown in popularity, seeing about 200,000 unique food purchases last year.

Hilgenberg spent much of her lifetime learning how to match seeds with soil and growing conditions, perfecting each step. She lives with the rhythm of the seasons. “We are moving back in the right direction,” she said. “There’s something exciting about eating freshly grown vegetables seasonally. It’s always new and nutritious.”

Hilgenberg begins planning a year in advance for each growing season, mapping out what she will plant and how it will be arranged for display. Seeds for cool-season plants begin to grow in the Greenhouses in late winter, go into the ground in April, and are harvested in May and June. A similar cycle follows shortly after for warm-season crops.

This is Pettorossi’s first spring at the Garden, after beginning in his role in November. He eagerly welcomes the arrivals of produce this spring. “If you can get something at the peak of freshness it always tastes better,” he said. As for the menu, “the season definitely dictates it,” he explained. “The menu features a lot of specials, depending on what we have in house.” No matter the season, he said the menu is always “fresh, mostly organic, local, and garden-inspired.”

Cool-season crops such as heirloom Tennis Ball butterhead lettuce (Lactuca sativa ‘Tennis Ball’) are the first to be ready this year. They will soon be joined by French Breakfast radish (Raphanus sativus ‘French Breakfast’), Hakurei salad turnips (Brassica rapa ‘Hakurei’), beets, and bunching onions. “All of our ingredients are very simple based on what they tell me they can grow,” he said, indicating that the most seasonal foods can be found in daily specials that he plans a day ahead.

The connection from garden to table extends to connect people as well, from garden mentor to student, or from an individual to their culture or family traditions, for example. Hilgenberg loves hearing from garden visitors about their connections to the garden crops. She spent much of her childhood on her Norwegian grandparent’s farm in Iowa, building her own such connections.

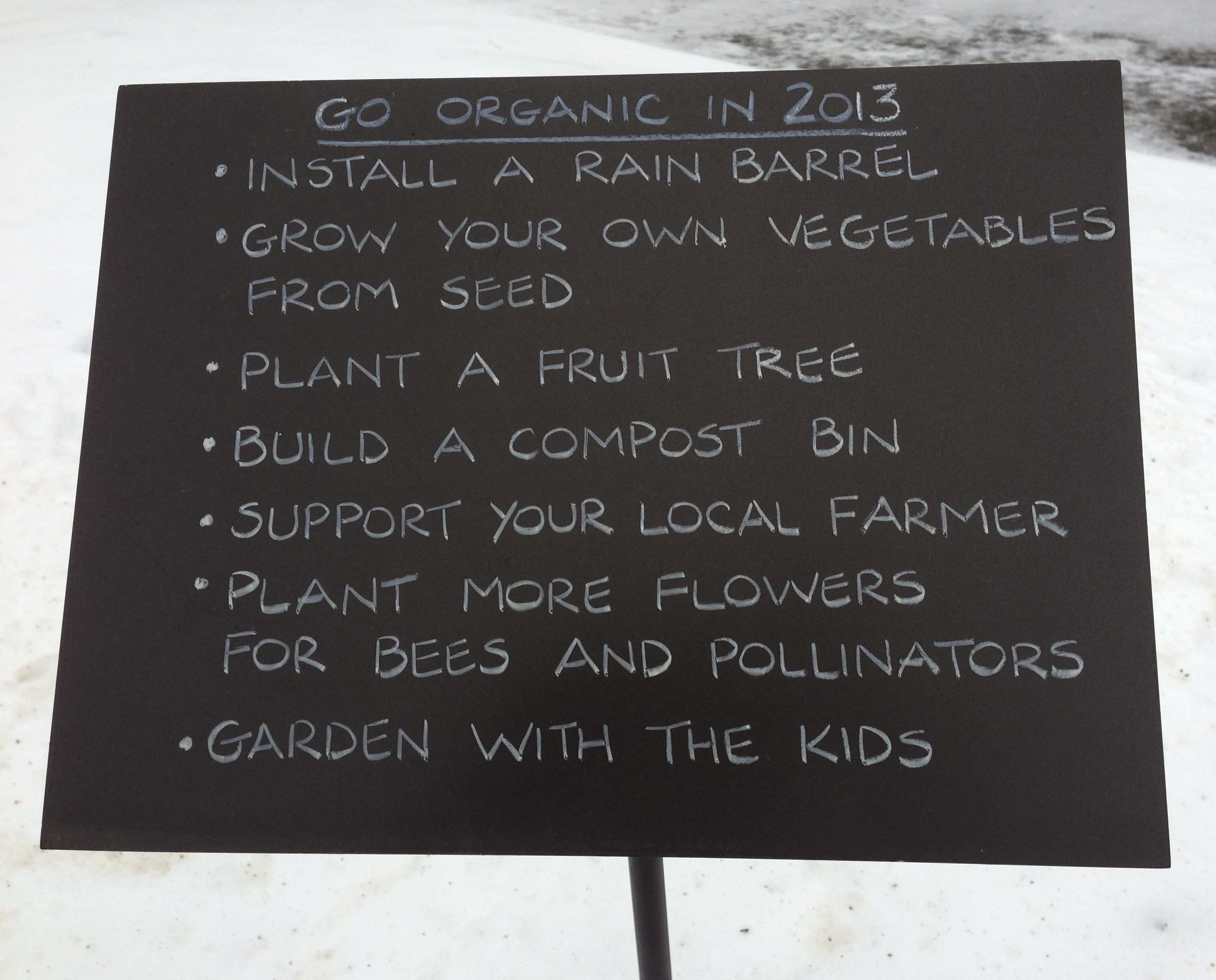

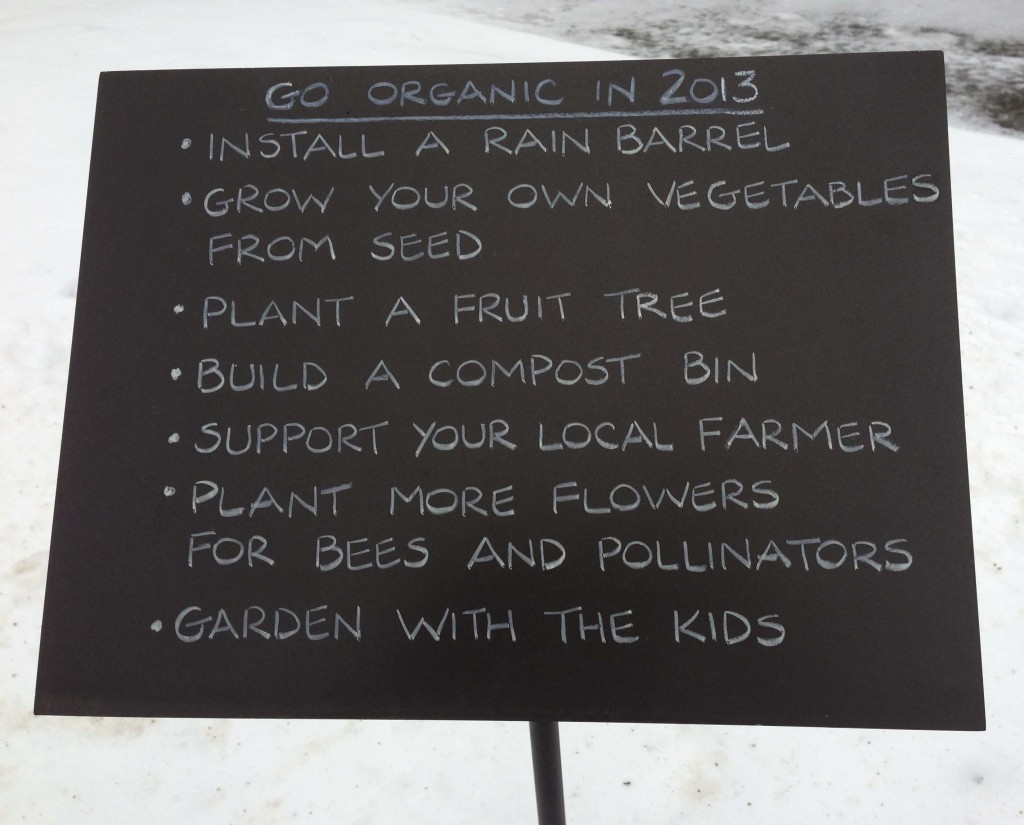

Hilgenberg makes a point to grow widely recognized plants in the garden each year, including herbs, edible flowers, and vegetables. She grows annual small fruits such as strawberries, gooseberries, and currants in addition to blueberries and bramble fruit. She also grows less common plants such as Marshall strawberries (Fragaria × ananassa ‘Marshall’), which she and her team propagated from three donated plants. Everything grown in the garden is done so organically. “I think it’s interesting for people to try different local varieties,” she said. Many, she explained, cannot be found in a typical grocery store, especially in organic form.

This year, several beds have been planted in the French potager style, and others laid out to mirror the gardens of Monticello. There are two beds planted with vegetables people may have seen in seed houses in 1890, the same year the Chicago Horticultural Society was founded. In honor of the Society’s 125th anniversary, seeds were made available through seed catalogs, the Seed Savers Exchange, and other sources. Edible flowers, such as Empress of India nasturtium (Nasturtium ‘Empress of India’), artfully border beds of radish, rutabaga, and turnips, for example. In addition, she included carrots, kale, collard, and three varieties of cabbage (Brassica oleracea): ‘Mammoth Red Rock’, ‘Early Jersey Wakefield’, and ‘Perfection Drumhead Savoy’. Each one was selected because it is adapted to our local growing conditions, a process Hilgenberg and her staff, volunteers, and interns have mastered over the years. Last year, they grew and harvested two tons of produce. The year before, that was combined with a bumper apple crop for 6,000 pounds of production.

How does the chef manage to find a way to serve even the most unusual varieties with style? “I always try to add a little acid [such as lemon or vinegar] to food because acid makes flavors pop,” he advised. “A lot of lettuces are sweet, but others have a bitterness to them,” he added, “so you would have to find that perfect vinaigrette to go with that bitterness,and maybe add a touch of honey or something sweet.”

In addition to growing and preparing food at the Garden, “we are also this amazing workforce and training program for underserved youth and adults,” said Resnick, who explained that participants in the Windy City Harvest program, with large growing beds off-site, provide a significant amount of produce for the Garden View Café and learn to sell their produce at farmers’ markets. On-site each year, a few Windy City Harvest interns work directly with Hilgenberg.

Anyone walking through the Fruit & Vegetable Garden today may see the beginnings of a dish they can enjoy in the café by early summer. The season will continue to evolve in coming months, with the Garden Grille opening in late May. In June, warm-season crops such as heirloom corn, Japanese Nest Egg summer squash (Cucurbita pepo ‘Japanese Nest Egg’), White Patty Pan squash (Cucurbita pepo var. melopepo ‘White Patty Pan’), Yellow Pear tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum ‘Yellow Pear’), and Blueberry Blend tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum ‘Blueberry Blend’) will replace the spring plantings in the Fruit & Vegetable Garden, giving way to new edible discoveries.

©2015 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org