David Sollenberger is building a time machine. He is capturing the prairie of today so that it can appear again in the future.

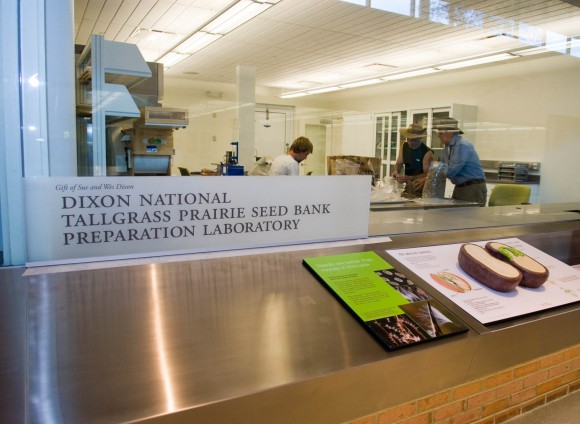

Moving about the Dixon National Tallgrass Prairie Seed Bank Preparation Laboratory at the Chicago Botanic Garden, Sollenberger works with a combination of everyday and high-tech tools. Brown paper bags filled with seeds scatter the windowsill, while metallic seed-drying machines with dials, switches, and gears line a wall. A long, stainless steel work table in the middle of the room is often surrounded by a team of focused volunteers.

The pulse of this active lab is the heartbeat of the Garden’s Seed Bank — a living collection of plant seeds reserved for potential future plantings.

“Tallgrass prairie is a globally threatened ecosystem, and we’re working hard to preserve what is left,” said Sollenberger, Seed Bank manager at the Garden.

While the prairie was once visible from horizon to horizon in the Midwest, it is now reduced to small, disconnected pieces of land that struggle to survive. While many of those remnants are protected from threats such as continued development, they remain fragile due to their disconnect from other natural areas and impending threats such as climate change. Seeds preserved in a seed bank can be used to create new habitat, or used to enhance existing areas in the future.

Prairie Protocol

The Garden began its Seed Bank as a part of an international effort led by the Millennium Seed Bank and the Bureau of Land Management’s Seeds of Success program. Together with partners from across the globe, they banked 10 percent of the world’s flora by 2010. Then, the Garden chose to continue to save seeds regionally, along with Seeds of Success.

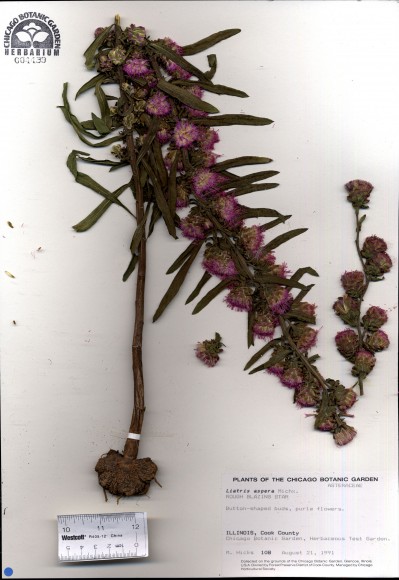

During warmer months, Sollenberger and a small group of contractors individually go into the field to gather seeds from a list of 544 target species. Each year they visit parts of the 12 interconnected ecoregions of the tallgrass prairie system, including wetlands, meadows, and prairies. Although there are more than 3,000 prairie species in the Midwest alone, Garden scientists identified a critical list of plants to focus on that are important species within the habitats they represent.

Following collection protocols established by the Millennium Seed Bank, they try to collect seeds from at least 50 plants in a population, which allows them to capture up to 95 percent of the population’s genetic diversity. When they do, they can share a section of the collection with national seed banks for backup storage.

However, due to the small size of many prairie remnants, there are sometimes fewer than 50 individual plants of a species in a population. In that case, Sollenberger explained, they collect along maternal lines, which means that seeds are collected separately from each plant. This results in a systematic representation of the genetic diversity of a species within a population.

Time Traveling

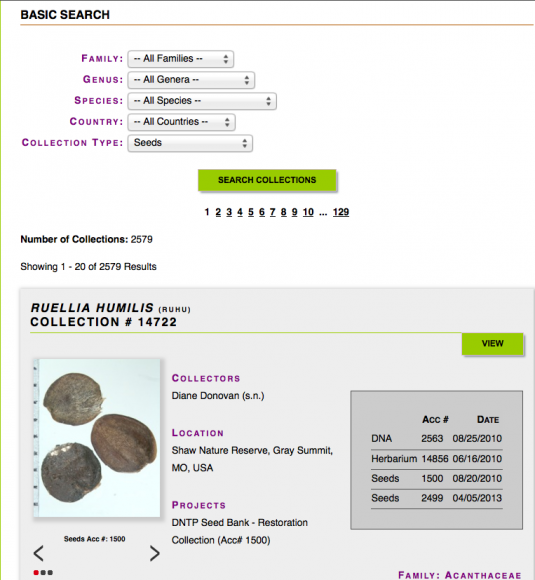

During winter in the laboratory, the collected seeds are first sorted and cleaned. It can be a meticulous and time-consuming process. But Sollenberger uses a number of techniques to add efficiency.

To sort viable seeds (those that hold an embryo inside) from those that are empty hulls, the team loads a batch into a large, clear cylinder with a motor-run fan called a column blower. When the seeds are blown about within the container, the heavier ones fall to the bottom while the lighter ones rise to a top shelf and can be disposed. They also use an X-ray machine to look inside a sample of seeds to determine what percentage is filled and potentially viable.

For seeds from the Aster family, goldenrods, and milkweeds, the team must first remove the silky hairs, or pappus. First, seeds are rolled on a rubber mat to loosen the pappus.

Then, they are run through a typical Shop-Vac that separates the pappus from the seeds. By using this process, “we’ve been able to improve the quality of the seeds,” noted Sollenberger. “It decreases the volume of seeds so there is less packaging, which allows for more space in the seed vault, and it improves our ability to separate light, non-viable ‘empty’ seeds and other light extraneous plant materials (chaff) from heavier, potentially viable ‘filled’ seeds.”

Throughout this process, seeds are stored in the dryers. There, they are dried to 15 percent humidity, which is critical for their successful storage at minus 20-degrees Celsius. Using this process, the majority of Midwestern prairie seeds can be stored for up to 200 years.

Early in his career, David Sollenberger helped to build the Garden’s Dixon Prairie. Learn more about his work. Bring your own seeds to our annual Seed Swap, Sunday, February 23.

Another few months of seed sorting await Sollenberger and his team, but he is already thinking of spring. “We take a breath in springtime when everyone else is busy,” he chuckled. It is then that he likes to visit McDonald Woods to soak in the beauty of a truly native natural area, before heading out in the summer to collect the next batch of seeds.

©2014 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org