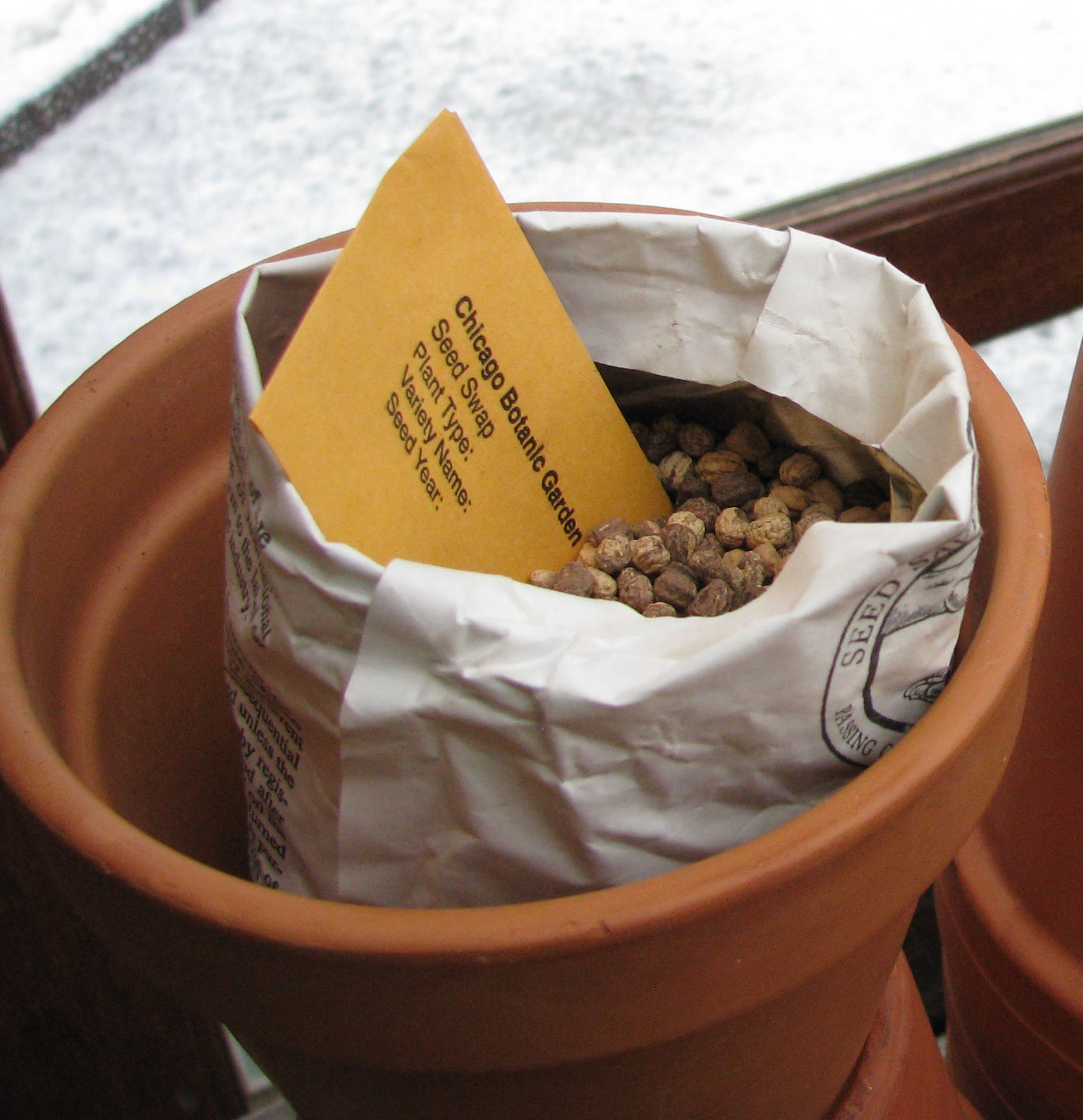

It’s snowy outdoors at the Chicago Botanic Garden. But serious gardening is underway indoors, where master gardener training has begun.

The Garden’s Plant Information Service help desk typically recruits 20 new master gardener interns from each biannual training session. Master gardeners answer your questions!

Every two years, the Garden becomes a teaching site for the University of Illinois Extension Master Gardener program. This year, the ten-week course, which started January 16, saw a record number of students enroll in on-site (93) and online (31 — triple the number of screen users as last session) classrooms.

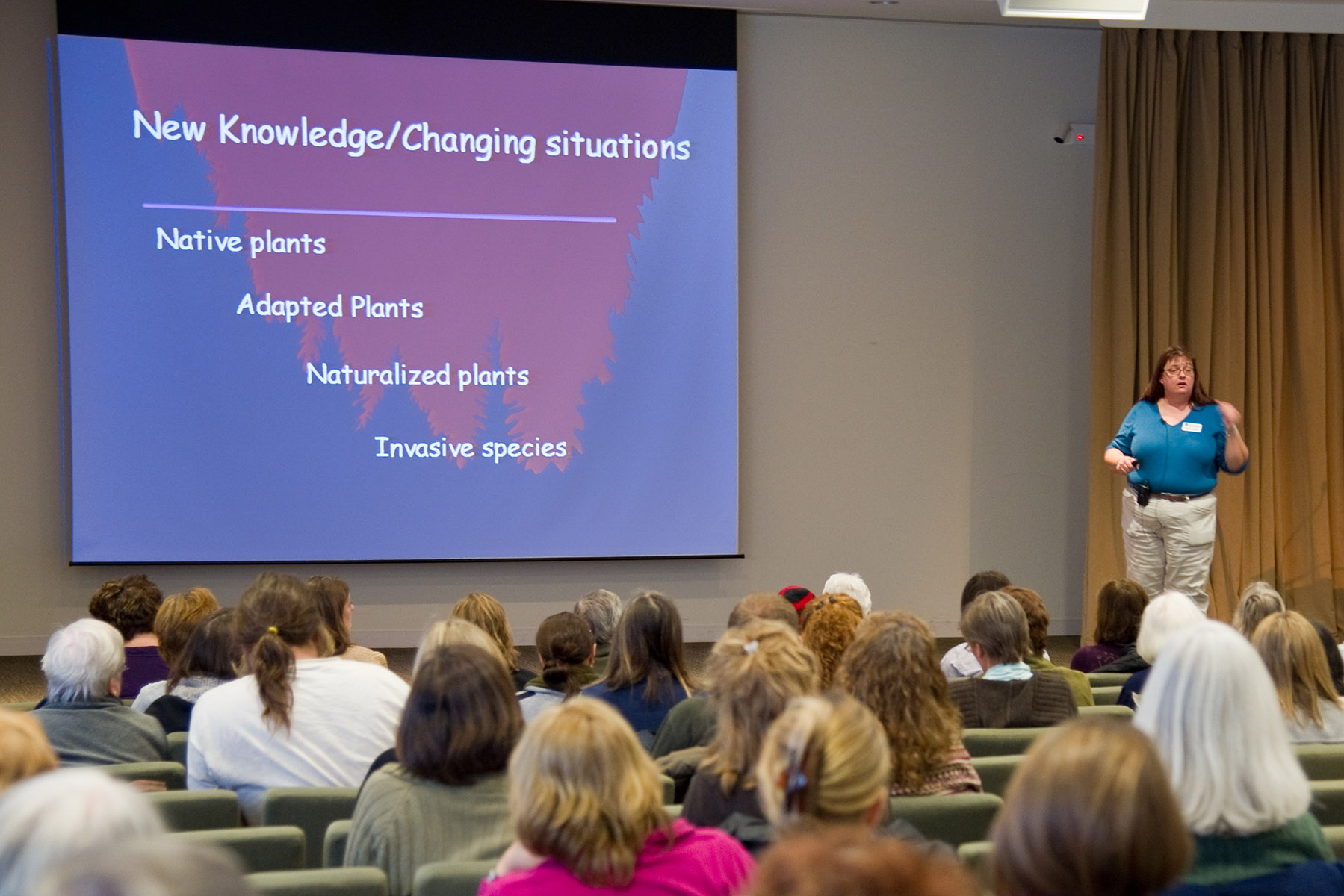

What are those 124 folks up to so far? They’ve finished sessions in topics including botany, soils & fertilizers, and woody plants. (Herbaceous plants, vegetables, fruits, turf, plant pathology, insects, and IPM/pesticide safety are up next.) They’re learning skills which are key to the program, including how to be a volunteer community educator — the true definition of a master gardener.

Lessons learned along the way include:

1. You don’t have to know everything. Yes, master gardener training is a crash course with lots of information coming at you fast. And, yes, there’s a test after every week’s session (it’s open-book, and you can take it at home). The real skill is to learn about the resources with the answers to the questions you’ll be fielding as a volunteer. As one instructor puts it, “there are two kinds of knowledge: what you already know, and what you know you can find the answer to.” The master gardener program teaches both.

2. The educators bring some interesting stuff to class. While class is lecture-based, there are plenty of PowerPoint visuals to help you picture what you’ll encounter out in the Garden. In the Soils & Fertilizers class on January 23, instructor Ellen Phillips brought soil samples, and explained soil porosity with the aid of…sponges!

3. You learn from everyone in class. Most classes have a Q & A session, and that’s when things can really get interesting. The real-life questions that fellow master gardener trainees bring up in class are the same questions you’ll be asked by the public. Many an “after-school” conversation, and many a gardening friendship, have begun from a question asked in class.

4. You identify your real interests. Are you a natural teacher? A community organizer at heart? Or a home gardener with decades of skills to share? After successfully finishing the course, master gardener trainees head out to master gardener internships, with lots of opportunities to find a volunteer situation that truly fits their interests.

5. You realize that this is a special program. Started in Illinois back in 1975, the master gardener program began as an aid to agricultural extension officers who needed to be out in the field helping farmers, but also needed volunteers to run the office and answer day-to-day questions from the community. (It still functions that way in some rural counties.) Today, the program is a shining example of public education at work, as university/research-based knowledge gets passed on from master gardener instructors to master gardener trainees to the public, in communities all over the state.

Although the next on-site master gardener session won’t start at the Garden until 2015, we offer the course every year online! There are also different University of Illinois county extension offices that offer the program each year. Think about your schedule, talk to our Plant Information Service volunteer master gardeners, and do some research about the program on our website. See you at the next master gardener training!

©2013 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org

Keep your home bouquet longer with these quick tips from Nancy Clifton, horticultural program specialist:

Keep your home bouquet longer with these quick tips from Nancy Clifton, horticultural program specialist: