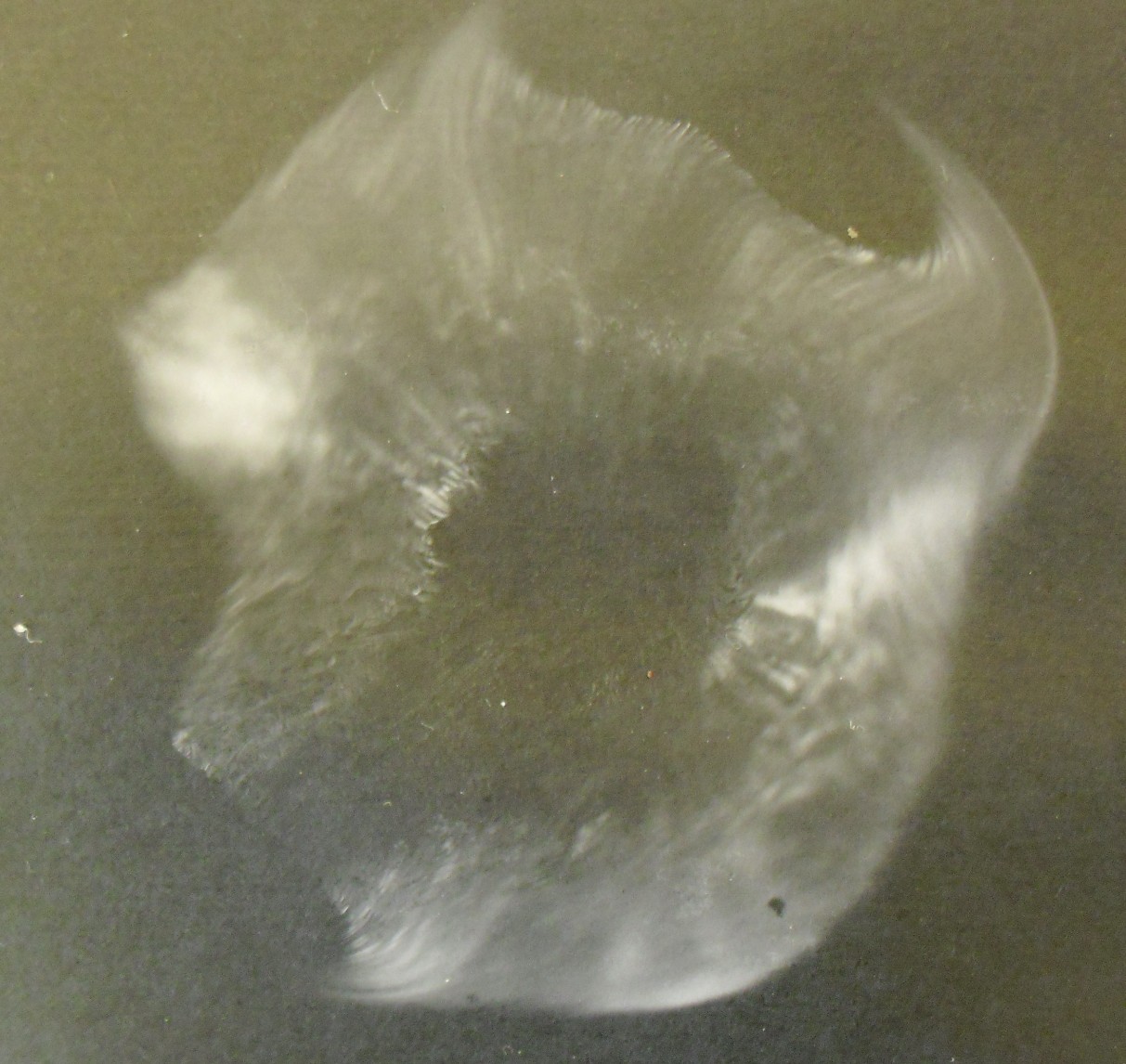

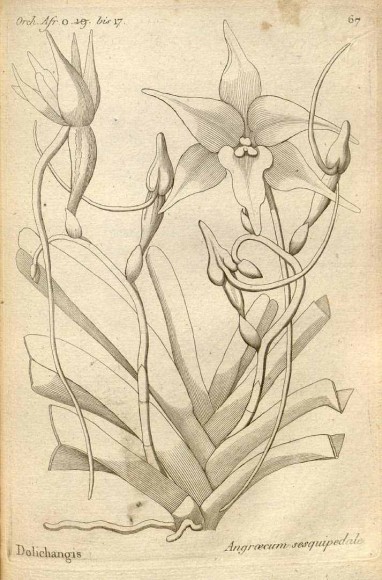

There’s something very special about this orchid. Can you tell what it is?

If you guessed that it was the long tubular structure coming from the back of the flower, you are right! That spur contains energy-packed nectar and is the reason this plant has a place in history.

Discovery

Angraecum sesquipedale was first described in 1822 by French botanist Louis-Marie Aubert du Petit-Thouars and would be shrouded in mystery for decades after. It arrived in the United Kingdom 33 years later.

At the time this orchid was discovered, transporting plants from one continent to another was extremely difficult and often unreasonable. The long sea journey, combined with polluted conditions in industrialized cities, made it difficult to collect and maintain specimen plants. This would all soon change.

It was in 1829 that Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward discovered the mechanism that revolutionized horticulture and botany forever.

The Wardian Case

Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward was an English doctor who spent most of his life in eighteenth-century London. In his youth, he perused the writings of Linnaeus and spent some time in Jamaica, which fostered his love of entomology and botany. As an adult, Ward was inspired to create a wall of ferns and mosses in his own yard, but failed due to the polluted air of East London. He was distraught.

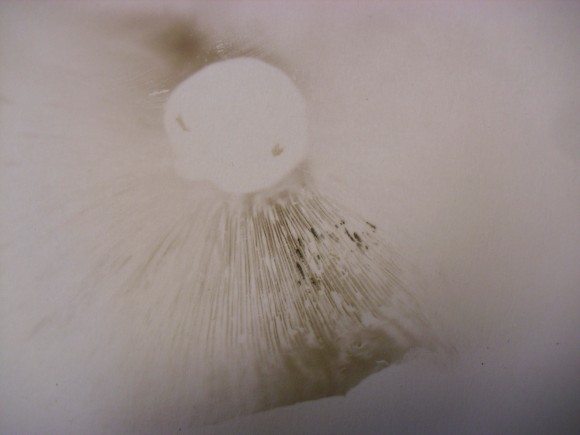

In the summer of 1829, Ward took a glass jar and placed a hawkmoth chrysalis inside, atop a bed of moist leaf mold. Ward regularly checked on the progress of the moth, finding that before it hatched, grasses and a fern emerged from the leaf mold. Ward observed that the glass jar retained moisture because as it warmed up, water evaporated, condensed on the glass, and returned to the base of the jar, never escaping. With this success he repeated his experiment and, to his delight, found that he could keep plants growing within the chamber for years. His discovery brought about the invention of the Wardian case, the predecessor to the modern terrarium. He wrote extensively about this in his book, On the Growth of Plants in Closely Glazed Cases. Soon the Wardian case became a popular feature of the parlor in Victorian society. These parlor versions, both tabletop and freestanding forms, often held one or more plants and could be rather ornate.

In 1843, the Wardian case was used for the first time to bring plants from China by sea. The director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, observed that in 15 years, the Wardian case brought six times as many plants as had been imported in the last century. If you do the math, that means it made importing plants almost 40 times as efficient as regular ocean travel! This was of particular use to collectors like James Bateman, a wealthy landowner who sponsored several plant exploration trips through the Royal Horticultural Society. One such trip would bring several rare Angraecum sesquipedale from Madagascar to England, and in 1862, this plant would find its way to one of the prominent figures in history.

Charles Darwin

By 1862, Charles Darwin had already become a prominent figure internationally. Having published On the Origin of Species three years earlier, Darwin was already the subject of scrutiny by religious groups and scientists who disagreed with his theories on evolution and natural selection. In this same year that he received a number of orchids from Bateman, Darwin published his book The Various Contrivances by Which Orchids are Fertilised by Insects, which proposed that Angraecum sesquipedale must be pollinated by a “huge moth with a wonderfully long proboscis” (or straw-like tongue). He proposed that it might be a Sphingidae moth since these are typically large. No such moth was known to exist on Madagascar.

Though largely overlooked by the public, his proposal became a subject of controversy, particularly in the religious community. Critics attributed any existence of such a creature to be by divine will and not natural selection; most mocked the possibility of such a moth existing. Others viewed his prediction with skepticism since only smaller moths had been discovered in Madagascar.

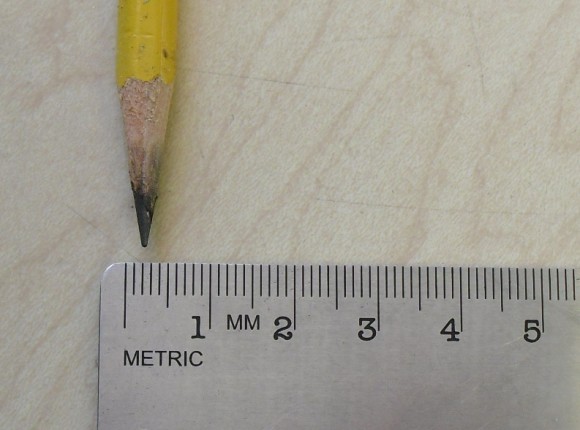

In 1903, 21 years following Darwin’s death, a subspecies of moth known as Xanthopan morgani praedicta, Morgan’s Sphinx moth, was found in Madagascar. This moth has a wingspan of 5 to 6 inches and a proboscis of 10 to 12 inches long. The subspecies name, praedicta, was intended as an homage to Darwin’s prediction that such an insect existed.

Angraecum sesquipedale, frequently referred to as Darwin’s Orchid, is currently being displayed in the Greenhouse Gallery of the Orchid Show (purchase tickets here) this year.

©2014 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org