Month: May 2014

Plant Conservation Is Happening Right Over Your Head

What if the next plant conservation project wasn’t down the street, or in the neighboring county, or far away in the wilderness? What if it was right above your head, on your roof? In our increasingly urban world, making use of rooftop space might help conserve some of our precious biodiversity in and around cities.

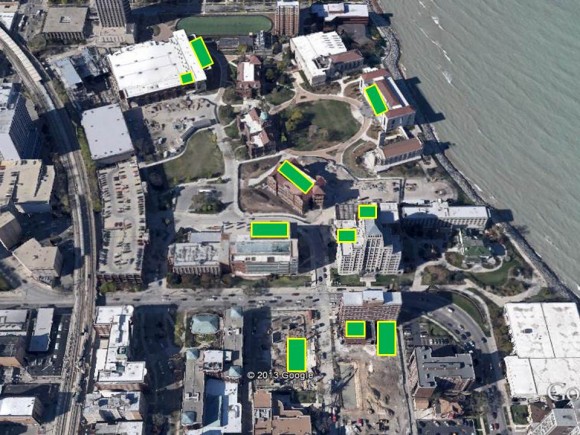

Unfortunately, native prairie plants have lost most of their natural habitat. In fact, less than one-tenth of one percent of prairies remains in Illinois—pretty sad for a state whose motto is the “Prairie State.” As a Chicago native, I found this very alarming. I thought, “Is it possible to use spaces other than our local nature preserves to help prevent the extinction of some of these beautiful prairie plants?” With new legislation at the turn of the century that encouraged the construction of many green roofs in Chicago, it seemed like the perfect place to test a growing hypothesis I had: maybe some of the native prairie plants that were losing habitat elsewhere could thrive on green roofs.

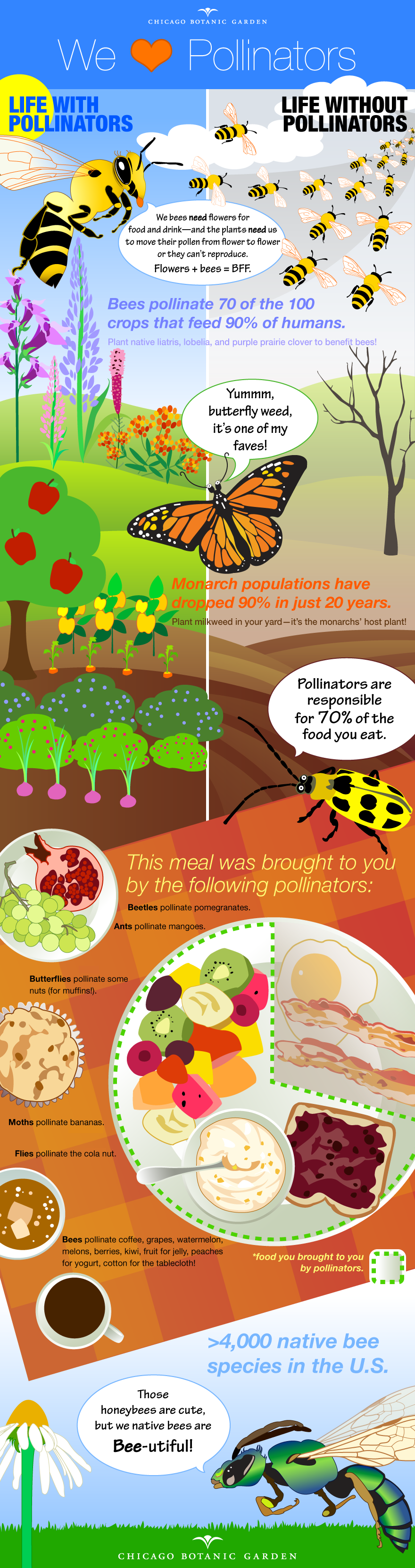

This idea brought me to the graduate program in Plant Biology and Conservation, a joint degree program through Northwestern University and the Chicago Botanic Garden. Here, I am investigating the possibility that the engineered habitats of green roofs can be used to conserve native prairie plants and the pollinators that they support.

Since I began the program as a master’s degree student in 2009, I’ve learned a lot about how native plants and pollinators can be supported on green roofs. For my master’s thesis, I wanted to see if native wildflowers were visited by pollinators and if they were receiving enough high-quality pollen to makes seeds and reproduce. Good news! The nine native wildflower species I tested produced just as many seeds on roofs as they normally do on the ground, and these seeds are able to germinate, or grow into new plants.

Once I knew that pollinator-dependent plants should be able to reproduce on green roofs, I set out to learn how to intentionally design green roofs to mimic prairies for my doctoral research. I started by visiting about 20 short-grass prairies in the Chicago region to see which species lived together in habitats that are similar to green roofs. These short-grass prairies all had very shallow soil that drained quickly and next to no shade; the same conditions you’d find on a green roof.

I’m now setting up experiments that test the ability of the short-grass prairie species to live together on green roofs. Some of these experiments involved using seeds as a cheap and fast way of getting native plants on the roof. Other experiments involved using small plant seedlings that may have a better chance of survival, although, as any gardener could tell you, are more expensive and labor intensive than planting seeds. I will continue to collect data on the survival and health of all these native plants at several locations, including the green roof on the Daniel F. and Ada L. Rice Plant Conservation Science Center at the Garden.

Ideally, I would continue to collect data on these experimental prairies to see how they develop over the next 50 years and learn how the plants were able to support native insects, such as pollinating bees and butterflies. But I didn’t want my Ph.D. to last 50 years so instead, I decided to collect the same type of data on green roofs that have already been around for a few decades. Because the technology is still relatively new in America, I had to go to Germany to collect this data, where the history of green roofs is much older. Last year, through a Fulbright and Germanistic Society of America Fellowship, I collected insects and data about the plant communities on several green roofs in and around Berlin and learned that green roofs can support very diverse plant and insect communities over time. We scientists are just starting to learn more about how green roofs are different from other urban gardens and parks, but it’s looking like they might be able to contribute to urban biodiversity conservation and support.

Now that I’m back in Chicago and have been awarded research grants from several institutions, I’m setting up a new experiment to learn about how pollinators move pollen from one green roof to another. I’ll be using a couple different prairie plants to measure “gene flow,” which basically describes how pollen moves between maternal and paternal plants. If I find that pollinators bring pollen from one roof to anther, this means that green roofs might be connected to the large urban habitat, rather than merely being isolated “islands in the sky,” as some people have suggested. If this is true, then green roofs could also help other plants in their surroundings—more pollinating green roof bees could mean more fruit yield for your nearby garden.

There are still many questions to be answered in this new field of plant science research. I’m very excited to be learning so much through the graduate program at the Garden and to be collaborating with innovative researchers both in Chicago and abroad. If you’re interested in keeping up with my monthly progress, please visit my research blog at the Phipps Conservatory Botany in Action Fellows’ page.

And if you haven’t already done so, I hope you’ll get a chance to visit the green roof at the Plant Science Center and see how beautiful plant conservation happening right over your head can be!

©2014 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org

Happy Birthday, Rachel Carson

Thank you, Rachel Carson.

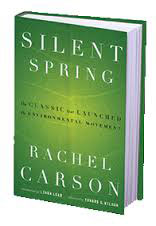

For me, personally, Silent Spring had a profound impact. It was one of the books we read at my mother’s insistence and then discussed around the dinner table. . . . Rachel Carson was one of the reasons why I became conscious of the environment and so involved with environmental issues. Her example inspired me to write Earth in the Balance. . . . Her picture hangs on my office wall among those of political leaders. . . . Carson has had as much or more effect on me than any of them, and perhaps than all of them together.

—Vice President Al Gore, “Introduction,” Silent Spring, (1994 edition), xiii

My mom was a grade school teacher. During a brief period where she stayed at home with children, she became an environmentalist. It all began with the book Silent Spring. My mother read about chemicals used in farming post-World War II and the decline of birds, and that was it; she had to take action. She remembers going to her parents’ house, and my grandfather was going around the yard, spraying DDT without protection, as his grandchildren played. He had a big bottle of DDT in the garage that had gone unnoticed until then. My mother could not believe what was happening and stopped him immediately. She had her dad throw out all pesticides. My grandfather didn’t realize there was any danger, as these chemicals promised a beautiful, American-dream green lawn. I remember at family gatherings, our family kept saying to my mother, “Elaine, what are you so worried about?”

My mom was a grade school teacher. During a brief period where she stayed at home with children, she became an environmentalist. It all began with the book Silent Spring. My mother read about chemicals used in farming post-World War II and the decline of birds, and that was it; she had to take action. She remembers going to her parents’ house, and my grandfather was going around the yard, spraying DDT without protection, as his grandchildren played. He had a big bottle of DDT in the garage that had gone unnoticed until then. My mother could not believe what was happening and stopped him immediately. She had her dad throw out all pesticides. My grandfather didn’t realize there was any danger, as these chemicals promised a beautiful, American-dream green lawn. I remember at family gatherings, our family kept saying to my mother, “Elaine, what are you so worried about?”

We became a family that ate whole wheat bread, and got the 1970s equivalent of CSA (Community Supported Agriculture) boxes. I would say that this book changed my childhood.

Some highlights:

- My mom baked organic whole wheat bread every week; it was not commercially available yet. (Imagine going to middle school with a sandwich of PB&J on badly cut homemade whole wheat bread, surrounded by kids eating bologna on Wonder Bread white. My brother and I felt so out of place at the time. (And now it would be so accepted, wonderful, and charming.)

- We did not have a microwave.

- No pop. No junk food. No candy.

- Our suburban lawn had dandelions. Mom used a dandelion knife.

- We used nonphosphate detergent.

- We went to weird hippie health food restaurants in Chicago. For her birthday, my mom knew she would get her requested restaurant so she would pick the only organic one in town.

- There were no TV dinners (and we could watch one hour of television a day).

- We all got transcendental meditation mantras.

But I digress…

She was the co-founder of S.A.V.E.: Society Against Violence to the Environment. “When Zion’s nuclear power plant was being built, we felt that it was so close to a large city…I put a full-page ad in Highland Park News, and I wrote an article about nuclear waste and terrorists.”

When my mom wasn’t lying down in front of bulldozers, or arguing with the Park District of Highland Park or Highland Park High School about spraying grass that children played on, she was going door-to-door, stopping the spraying of mosquitoes in our town.

After we moved to San Diego, I remember lugging many heavy grocery bags filled with organic oranges and flour from San Diego State University’s co-op parking lot, ½ mile each way every week (several trips each time).

Later, when she got cancer, she endured the remark, “Oh, you with your organic food, you got cancer?”

Now you can find organic food everywhere. Who doesn’t meditate?

Teach your children well…

New times and different challenges…now we are concerned with global warming.

As Rachel Carson said:

“We stand now where two roads diverge. But unlike the roads in Robert Frost’s familiar poem, they are not equally fair. The road we have long been traveling is deceptively easy, a smooth superhighway on which we progress with great speed, but at its end lies disaster. The other fork of the road—the one less traveled by—offers our last, our only chance to reach a destination that assures the preservation of the earth.”

Thanks, Mom. You taught me about Mother Earth. I still don’t have a microwave. I eat organic food, grow some my own, and am lucky to work at a garden that cares about the environment. :)

©2018 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org

Strawberries

When I was 8 years old, I traveled with my family to Przysietnica, Poland, to spend the summer with relatives. My grandparents’ farm was the home base for my adventures with cousins and siblings. We spent hours in the breezy northern hills, picking the sweetest strawberries I ever had. They grew wild and tasted like candy. We often brought some back to share with the family, but there is nothing quite like a strawberry fresh off the plant.

The Cultivated Strawberry

The garden strawberry is the strawberry we most often think of when we think of strawberries. This is the strawberry from the clear plastic boxes you find at the grocery store. This strawberry is Fragaria × ananassa, which has only been around for about 260 years, and has undergone a lot of breeding in that time.

Fragaria × ananassa is actually a cross of the Chilean and Virginia (or wild) strawberry, which arrived in Europe in 1712 and 1624, respectively. The hybrid plant was discovered in the 1750s and recorded in 1759 by Philip Miller, a famous English horticulturist. He referred to it as the “pine strawberry” for its taste, which was similar to pineapple.

If you’re taken aback by this assessment of flavor, you’re not alone—the modern garden strawberry has undergone a great deal of breeding, which improved firmness but did little for its taste. Some of the modern breeding programs are working to fix this problem.

Fragaria × ananassa is not the only cultivated strawberry on the market. There are more than 20 species of strawberries worldwide, with only a small portion of those being grown in gardens for eating. Some of the popular species include the musk strawberry (F. moschata), the alpine strawberry (F. vesca), the Chilean strawberry (F. chiloensis), the Virginia strawberry (F. virginiana), Fragaria nipponica, and Fragaria viridis. Most of these strawberries originate in Europe (Fragaria nipponica is Japanese in origin); the Chilean and Virginia strawberries are the only cultivated New World species. While there are many edible strawberries, these tend to be the most popular.

Biology

Do you know how the strawberry got its name? The popular theory is that strawberries are so named because they are cultivated on straw. The truth is, strawberries were named before straw was ever cultivated. Have you ever seen strawberries growing? They spread by stolons, or above-ground roots. These stolons reach out, find a good moist spot away from the parent, and put out roots, producing a new clone of the mother plant. In this way, a single cultivar of strawberry can reproduce itself dozens of times and still be identical or nearly identical to the mother plant. The stolons that give rise to new strawberries are called “runners.” This habit of growing is what gave it its name; strawberries tend to be strewn (spread) about.

It’s generally accepted that strawberries will either produce runners or flowers. Though sometimes producing both simultaneously, the energy is usually dedicated to one task over the other. This is why there are three main types of garden strawberries: ever-bearing, day-neutral, and June-bearing. Strawberries tend to be June-bearing by nature, which means you’ll harvest your fruit in late spring to early summer. Though you sometimes end up with a second crop in fall, the June-bearing strawberry will produce runners for the rest of the year. Ever-bearing strawberries prefer to put their energy toward making fruit, so you’ll end up with few runners and strawberries several times per season. Day-neutral will produce strawberries continually throughout the year, and create the fewest runners.

“Fruit”

Did you know that a strawberry isn’t a fruit? It’s an “aggregate of achenes on a swollen receptacle.” Achenes are those little specks on the surface of the strawberry; these are the true fruit of the strawberry. The achenes break apart much the way that sunflower seeds do. An aggregate refers to a cluster or grouping, and the receptacle is the part of a flower that bears the sexual organs.

Seems complicated? Try this: cut a strawberry flower in half and look inside.

The female parts of the flower (pistils) are near the top center of the flower with the male parts (stamens) forming a ring around the outside. When the flowers are pollinated, the area under each pistil swells and turns red. When the whole flower is pollinated, you end up with a perfectly red strawberry.

Humans have known about strawberries for hundreds of years, but strawberries only became commercially common within the past century, thanks to refrigerated trucks and breeding programs that gave strawberries their firmness. Ever since, they have been one of the top ten favorite “fruits” in the United States.

©2014 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org

Grafting Tomatoes

Grafted tomato plants are available at garden centers and through mail order nursery catalogs, but sell out quickly, as the idea has captured the interest of home gardeners, farmers, and professional greenhouse growers.

An ancient art and science long used on fruit trees, grafting is the placement of the tissues of one plant (called a scion) onto another plant (called a stock). The rootstock is thought to impart disease resistance and increased vigor to a less vigorous—perhaps heirloom—tomato grafted on the top, producing more tomatoes over a longer period of time.

Curious about the process and whether the price tag could be justified—grafted plants run from $9 to $18 a plant—I decided to graft some tomato plants myself and grow them out. My first foray was in winter 2013. The Chicago Botanic Garden’s propagator in the plant production department, Cathy Thomas, had just returned from a conference at Longwood Gardens, where one of the topics was grafting vegetables. She willingly supported my quest and enthusiastically discussed the details with me.

The process seemed fairly straightforward after we settled on which varieties to graft together. Deciding to graft the cultivar ‘Black Cherry’ onto ‘Better Boy’ rootstock, we worked with tiny, 3-inch-tall tomato starts, taking care that the top and bottom stems of each plant were exactly the same diameter at the place they were to be grafted. Our grafting tools included clear silicon tubing cut to 10 to 15 millimeter lengths, a new, unused razor blade, and our tomato seedlings.

Starting by sanitizing our hands, we used a new razor blade to slice the stem of the scion (top graft plant) off at a 45-degree angle. The plastic tubing, soon to be the grafting clip that would bandage the graft union, was prepared by splitting it in half. All the leaves were removed from the scion, leaving only the meristem. (The meristem is the region of stem directly above the roots of the seedling, where actively dividing cells rapidly form new tissue.) Two diagonal cuts were made, forming a nice wedge to fit into the rootstock. The rootstock was split and held open to accommodate the scion. A silicon clip was slipped around the cleft graft. Newly grafted plants were then set into a “healing chamber,” a place with indirect light and high humidity, for up to a week. In the healing chamber, the plants can heal without needing to reach for light, which can cause the tops to pop off. We placed our new grafts in a large plastic bag in the Regenstein Fruit & Vegetable Garden greenhouse. The healing began.

Two weeks later, we had a dismal one-third survival rate! Much to my relief, the lone survivor was a superlative tomato plant in almost every way. Oh, what a strong tomato we had! My excitement rose—what if heirloom tomatoes could be as delicious and more prolific and adaptable? When soils warmed, we planted our grafted tomato out in the Fruit & Vegetable Garden, positioned right next to a ‘Black Cherry’ plant growing on its own root, so the differences would be easy to discern. Our hope was that we could address some of the ins and outs of grafting for the public, and the feasibility of DIY (do it yourself) for gardeners. Do grafted heirloom tomatoes have more vigor, better quality, and bear more fruit than ungrafted “own-root” heirloom tomatoes? Which has a more abundant harvest over a longer period of time?

Last summer, our grafted tomato plant certainly provided the earliest harvest. Comparatively, it was earlier to fruit than the plant grown on its own root by two weeks, and was prolific throughout the season. That being said, in the organic system of the Fruit & Vegetable Garden, our soils are nutrient-rich and disease-free in large part due to crop rotation and soil-building practices. The question used in marketing “Is the key place for grafted tomatoes in a soil that has disease problems?” didn’t apply to us. Are grafted tomatoes the answer for those with less-than-ideal environmental growing conditions? For greenhouse growers unable to practice crop rotation as a hedge against a build-up of soil-borne disease, or home gardeners who contend with cool nights and a short growing season, I would say yes, I think so, but at a cost.

When planning on grafting, growers must buy double the amount of seed and need to double the number of plantings (to account for the graft failure rate) to maintain the same number of viable seedlings to plant. Cathy and I tried our grafting project again this spring and are looking forward to growing ‘Stripes of Yore’ and ‘Primary Colors’ on ‘Big Beef’ hybrid rootstock. I swapped seed for these unusual varieties with a tomato enthusiast who attended our annual Seed Swap this past February. Our rootstock has excellent resistance to common tomato diseases: AS (alternaria stem canker), F2 (fusarium wilt), L (gray leaf spot), N (nematodes), TMV (tobacco mosaic virus), V (verticillium wilt).

We planted grafted tomatoes in the Fruit & Vegetable Garden, right alongside some of the other 52 varieties of heirloom and hybrid tomatoes.

©2014 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org