Despite all of the electronics and gadgets that surround us and demand our attention, a book is still one of the most thoughtful and personal presents to give and to receive at the holidays.

Here’s a quick quiz; fill in the blanks:

- This holiday, I just want to relax on the sofa with a good _____.

- My kids ask me to read that _____ to them every night.

- Our ____ club is meeting next Tuesday evening for some holiday cheer.

Does this sound familiar to you? It did to us! So we turned to our book experts—the staff at our Lenhardt Library—to ask for their recommendations for holiday gift books.

Their well-rounded, garden-oriented list covers botany, horticulture, landscape, cooking, arts, crafts, trees, birds, and vegetables—with occasional commentary from the librarians themselves. All selections are part of the Lenhardt Library collection—which means free check-out for members. (Another great reason to become a Chicago Botanic Garden member—click here to join.)

Eight selections are available to purchase at our Garden Shop, too. Shop online, visit the shop before/after your Wonderland Express visit, or come by to browse during holiday hours.

Of course, you can order from our Amazon Smile link; 5 percent of the profits go to support the Garden! https://smile.amazon.com/ch/36-2225482

We even included our library call numbers so you can find these books easily—and browse 125,000 other volumes—when you come to the library. We look forward to seeing you!

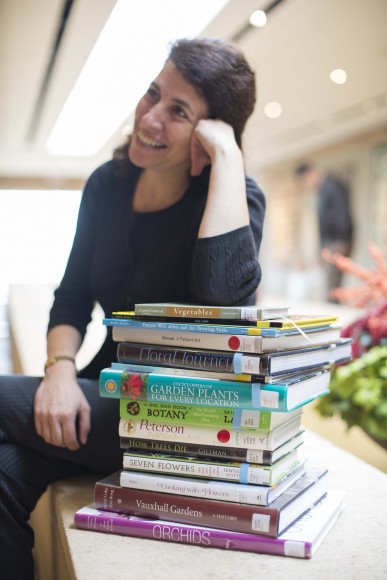

A Potted History of Vegetables by Lorraine Harrison

Guilford, CT: Lyons Press, 2011.

SB320.5.H27 2011

Compact, lovely to look at, and full of useful information, this is a beautifully illustrated and handy book that includes vegetable history, how-to’s, etc. This tucks nicely into a Christmas stocking, too.

—Ann Anderson, library technical services manager

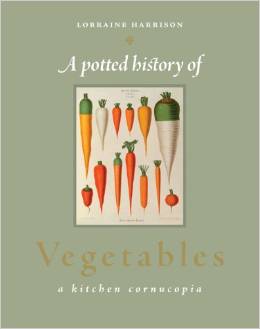

Bonsai: A Patient Art: The Bonsai Collection of the Chicago Botanic Garden by Susumu Nakamura, consulting curator; Ivan Watters, curator; Terry Ann R. Neff, editor; Tim Priest, photographer

![]() Purchase online from the Garden Shop

Purchase online from the Garden Shop

Glencoe, IL: Chicago Botanic Garden in association with Yale University Press, 2012.

SB433.5.C55 2012

This book captures our Bonsai Collection. It has stunning photographs, paired with copy that brings the world of bonsai to life.

Cooking with Flowers: Sweet and Savory Recipes with Rose Petals, Lilacs, Lavender, and Other Edible Flowers by Miche Bacher; photography by Miana Jun

![]() Available on-site at the Garden Shop

Available on-site at the Garden Shop

Philadelphia, PA: Quirk Books, 2013.

TX814.5.F5B33 2013

This book features common, everyday (and edible!) flowers used in fabulous ways—I’ve given this book to gardeners and to people who love to cook. The illustrations are lovely. The dandelion chapter first captured my interest (what could be easier to acquire?)…and then there was the lilac sorbet…

—Donna Herendeen, science librarian

Encyclopedia of Garden Plants for Every Location

editors Jenny Hendy, Annelise Evans

New York, NY: Dorling Kindersley Limited, 2014.

SB407.E53 2014

Destined to be dog-eared and brand new on the shelf, this book is an info book that gardeners of every type and experience level can trust for facts and advice.

—Leora Siegel, library director

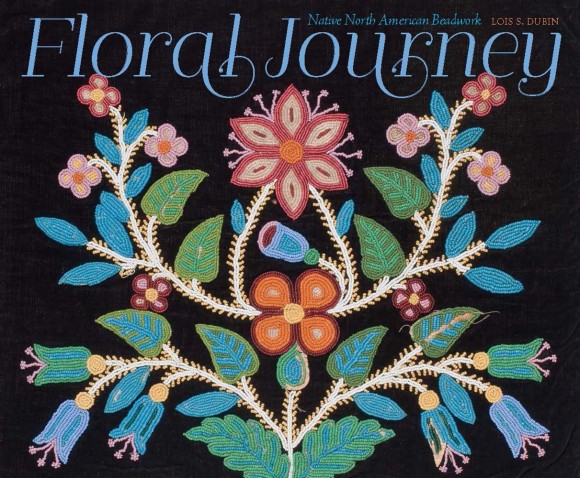

Floral Journey: Native North American Beadwork by Lois S. Dubin

![]() Available on-site at the Garden Shop

Available on-site at the Garden Shop

Los Angeles, CA: Autry National Center of the American West, 2014.

E98.B46D83 2014

This book features native American history, encoded in beadwork. Gift this book to history buffs, fashion fanatics, and craft-devoted friends, all sure to be gobsmacked by the sheer audacity and intricacy of it all. Read our full review here.

Ginkgo: The Tree That Time Forgot by Peter Crane

![]() Available on-site at the Garden Shop

Available on-site at the Garden Shop

New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2013.

QK494.5.G48C73 2013

Were you one of the lucky attendees at Peter Crane’s lecture at the Garden in 2013? In his beautifully written and realized book, the former director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, goes beyond botany and horticulture to cover the art, history, and culture of one of the planet’s most ancient trees. Read our full review here.

How Trees Die: The Past, Present, and Future of Our Forests by Jeff Gillman

Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2009

SD373.G55 2009

A thoughtful gift option for a deep thinker, this book impressed me both with the writing and its illumination of an often-overlooked fact: trees can live extraordinarily long lives. It’s a comfortably sized book for reading, too.

—Donna Herendeen, science librarian

Living Wreaths: 20 Beautiful Projects for Gifts and Décor by Natalie Bernhisel Robinson; photographs by Susan Barnson Hayward

![]() Available on-site at the Garden Shop

Available on-site at the Garden Shop

Layton, UT: Gibbs Smith, 2014.

SB449.5.W74R63 2014

The cover is so stunning that it compels you to open this new-on-the-shelves book, which is filled with step-by-step instructions for designs both simple and extravagant. Or buy the book for yourself, then gift your friends with your own handmade versions.

—Ann Anderson, library technical services manager

Orchids

photographs by Fabio Petroni; text by Anna Maria Botticelli; translation, John Venerella

![]() Purchase online from the Garden Shop

Purchase online from the Garden Shop

Novara, Italy: White Star Publishers, 2013.

Ovrz SB409.P48 2013

We admit it: we’re partial to orchids (The Orchid Show opens at the Garden on Valentine’s Day, 2015). We’re also partial to this coffee table-sized book as a great gift, filled with stunningly detailed and thoughtful photography of the world’s most beautiful flowers.

—Stacy Stoldt, library public services manager

Peterson Field Guide to Birds of North America by Roger Tory Peterson

Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Co., 2008.

QL681.P455 2008

Birds and plants go together. As a gardener, bird watcher and traveler, I’ve always wanted one ID book for the United States, not just the east or west. Slightly larger than the typical Peterson guide, this edition fits the bill.

—Donna Herendeen, science librarian

Plantiful: Start Small, Grow Big with 150 Plants that Spread, Self-sow, and Overwinter by Kristin Green

![]() Available on-site at the Garden Shop

Available on-site at the Garden Shop

Portland, OR: Timber Press, 2014.

SB453.G794 2014

What a great idea for a gardening book: focus on the plants that do the work themselves. “It spreads” was once anathema to a gardener, but this book takes a surprising and creative new approach to 150 “free” and garden-worthy plants.

—Christine Schmid, library technical assistant

Seven Flowers and How They Shaped our World by Jennifer Potter

New York, NY: Overlook Press, 2014.

SB404.5.P68 2014

Lotus, lily, sunflower, poppy, rose, tulip, orchid…author Jennifer Potter traces the powerful effects that seven simple but seductive flowers have had on history, civilization, and culture. Tulipmania? Orchid fever? The War of the Roses? All is revealed and explained in this compelling, lushly illustrated book.

—Leora Siegel, library director

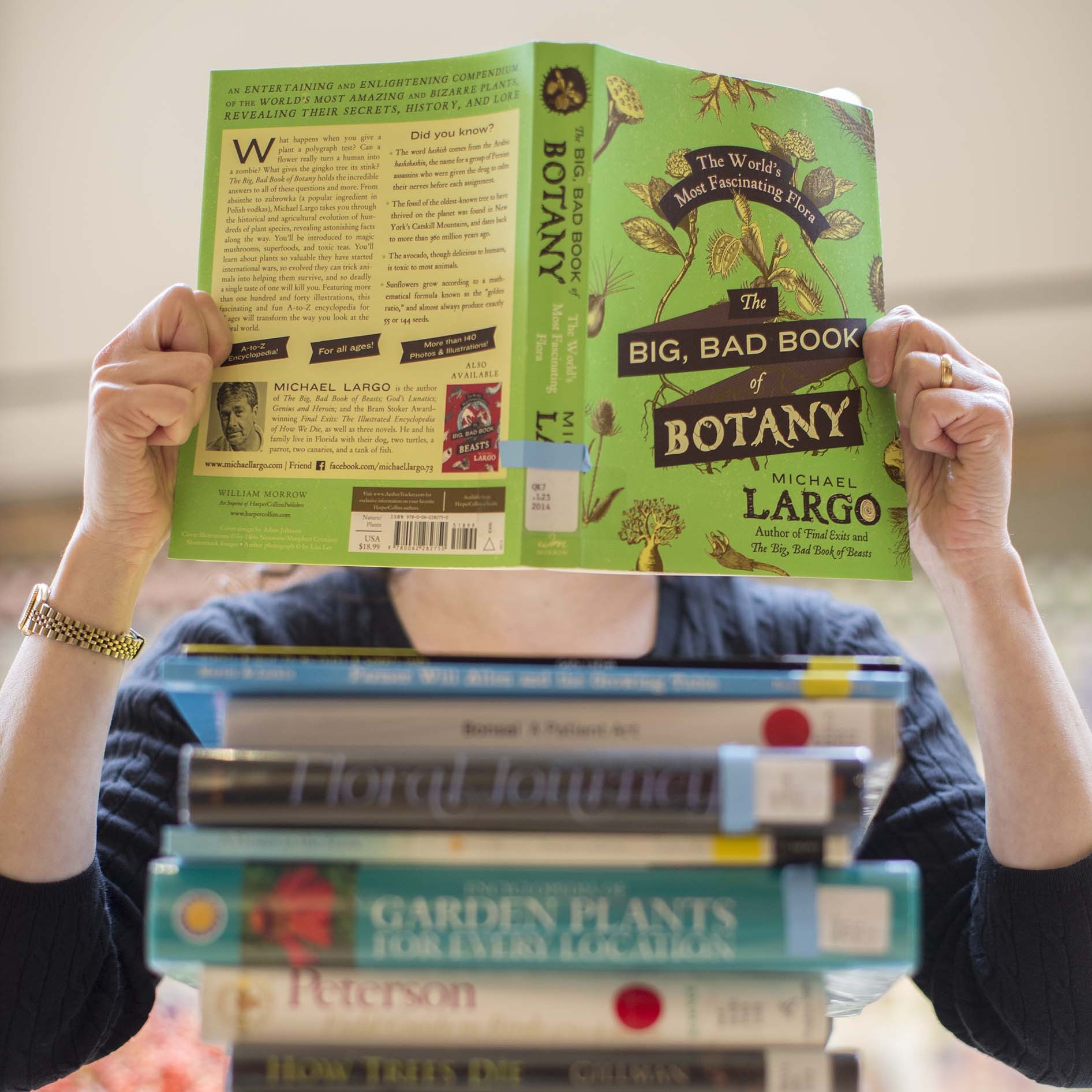

The Big, Bad Book of Botany by Michael Largo; illustrations by Margie Bauer

![]() Available on-site at the Garden Shop

Available on-site at the Garden Shop

New York, NY: William Morrow, 2014.

QK7.L25 2014

The cover alone is enough to propel you into this endlessly fascinating, fun, fact-filled, A-to-Z book. A great gift for anyone (any age!) who loves to cite a good fact, tell a shocking story, or learn about the natural world in unexpected ways.

—Leora Siegel, library director

Vauxhall Gardens: A History by David Coke and Alan Borg

New Haven, CT: published for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art by Yale University Press, 2011.

DA689.G3C65 2011

Similar to entertainment parks like Chicago’s Millennium Park or Denmark’s Tivoli Gardens, Vauxhall Gardens is mentioned everywhere in literature, but no longer exists. What was it like? Comprehensive and scholarly, this book explores the details—the history of social life, public gardens, culture—in a large format that does justice to the numerous period illustrations and maps.

—Stacy Stoldt, library public services manager

Especially for Kids

A Flower in the Snow by Tracey Corderoy

London: Egmont, 2012.

PZ7.C815354Flo 2012

A little child…a big bear…a golden flower…and the power of friendship. A book that never grows tired of being read aloud over and over again, it’s a fine gift/addition to your child’s/friend’s library.

—Christine Schmid, library technical assistant

Farmer Will Allen and the Growing Table by Jacqueline Briggs Martin

Bellevue, WA: Readers To Eaters, 2013.

S494.5.U72M325 2013

Kids need to know the true story of Will Allen, former basketball star, who creates gardens in abandoned urban sites to bring good food to every table. This book is inspiring and motivating (and he can hold a cabbage in one hand!).

—Ann Anderson, library technical services manager

The Giving Tree by Shel Silverstein

![]() Available on-site at the Garden Shop

Available on-site at the Garden Shop

New York, NY: Harper & Row, 1964.

PZ7.S39

This is a beloved classic, now teaching another generation about the nature of giving. Your child or young friend doesn’t know it yet, but this heartfelt and tender story, illustrated so beautifully by the author, will become a staple on the nightly story request list.

—Christine Schmid, library technical assistant

There’s a Hair in my Dirt! A Worm’s Story by Gary Larson

New York, NY: Harper Perennial, 1998.

PS3562.A75225T47 1999

Like so many fairy tales and fireside stories before it, this witty, funny tale also has a darker twist, fittingly revealed in the final panel. Adult fans of Gary Larson’s The Far Side might enjoy this book as much as the perceptive kids you’ll gift with it. It always makes me laugh…and scream.

—Stacy Stoldt, library public services manager

Want more inspiration? Check out the library section on our website for hundreds more book reviews. Happy Giving!

©2014 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org