The Garden has a bright and cheery answer for overcoming classroom winter doldrums: take a field trip to see the Orchid Show!

At a time when schools are tightening budgets and limiting field trips, you might think that an Outrageous Orchids experience is a frivolous excursion—but, in fact, this is a luxurious way to learn life science principles. Our programs are grounded in fundamental science concepts outlined in the Next Generation Science Standards. From Valentine’s Day to St. Patrick’s Day, students get meaningful science lessons as they enjoy the sensational display of colors and aromas in our Greenhouses.

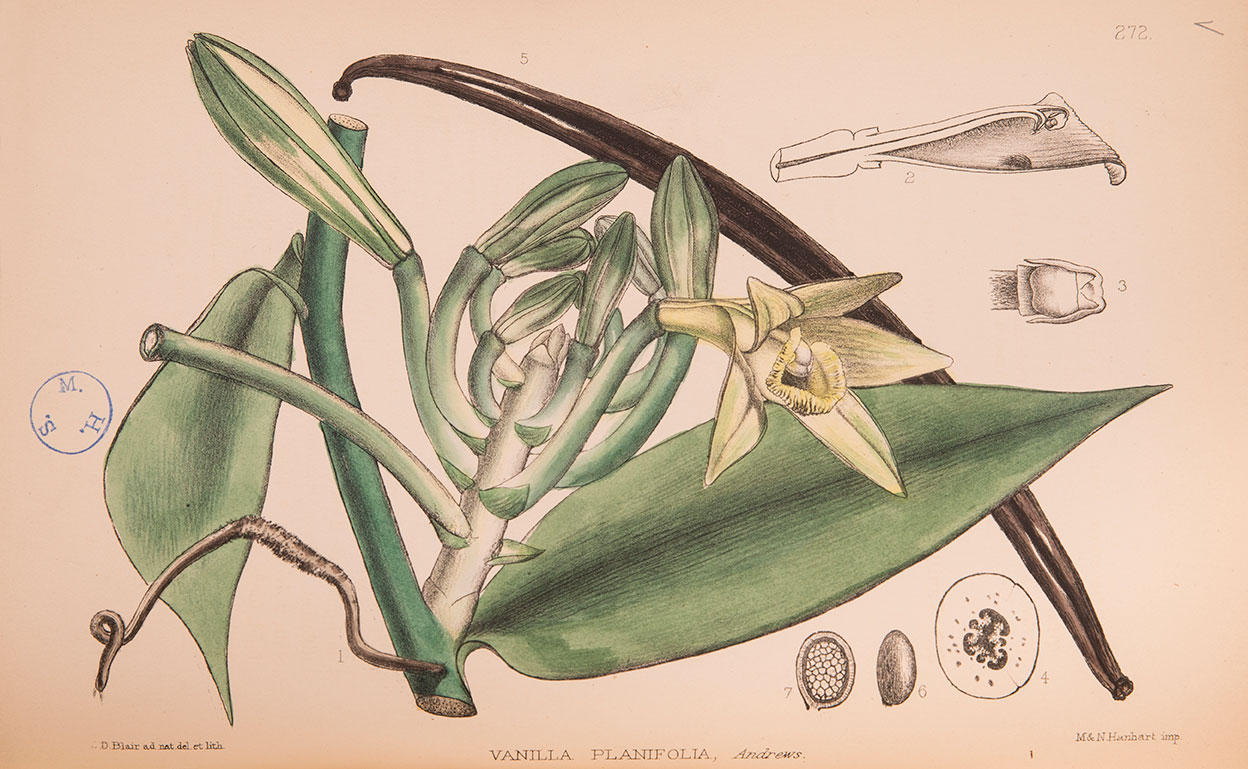

Field trips are tailored to suit different grade levels. Younger students study the variety of color and shapes found in the exhibition to identify patterns. Early elementary level students examine the structures of orchids to understand their functions. Upper elementary students recognize how tropical orchids have adaptations for survival in a rainforest. These core ideas about orchids apply to all plants and are essential for understanding ecosystems. There isn’t a more beautiful way to study plant science anywhere else in the Chicago region.

As if being surrounded by gorgeous flowers in the dead of winter weren’t enough to engage a person’s brain, each student also gets to transplant and take a tropical plant to continue the learning after the visit.

The Baggie Terrarium is a mini-ecosystem that reminds students of the water cycle and enables them to observe plant growth.

Make a Baggie Terrarium

Supplies:

- 1 zip-top bag (quart-size or larger)

- Potting soil, moistened

- A small plant or plant cutting (during Outrageous Orchids classes, we let students take a spider plant “pup” from a very large spider plant)

- Pour soil into the bag to fill about 2-3 inches deep. Use a finger to create a hole in the soil for the plant.

- Bury the roots of the plant in the hole and gently tap the soil around the base of the plant. If you are planting a stem cutting, place the stem in the soil and tamp around the base. If you have a larger bag, you can add more than one plant. Three different plants in a gallon size bag can make an attractive terrarium.

- Seal the bag, leaving about a 1-inch opening. Blow into the bag to inflate it and quickly seal the last inch tight so the air doesn’t all escape. The carbon dioxide in your breath is good for the plant, and will give the bag enough substance to stand up.

- Place the terrarium in a bright location, but not in direct sunlight. Remember that most tropical plants grow under the canopy of taller trees and do not need full sun. In fact, too much direct sun makes their leaves fade!

- Watch for tiny water droplets forming on the sides of the bag. These will gradually roll down the sides of the bag and re-water the soil. As long as the bag is completely sealed, it will stay moist and you will never have to open the bag or add more water. But if it dries out, you will need to water the plants.

You can leave your terrarium alone for a long time and not do anything but watch the plants grow. Eventually, they will outgrow the bag. Then you can transplant them to a pot if you like, or take cuttings and start another baggie terrarium.

Like all of our programs, Orchid Show field trips inspire young people to learn more about plants! Visit our website at chicagobotanic.org/fieldtrips for more information about these programs.

©2015 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org