For many bonsai tree species, early spring is the best time for repotting.

As the days get longer and the temperatures slowly increase, the roots of a bonsai gradually become active. During this time, the energy of the tree that was stored in the roots over the winter begins to move back up into the tree branches. As this happens, the dormant buds begin to swell. This swelling is the first sign that the tree is beginning to break dormancy. Over the next few weeks, the amount of energy from the roots to the branches increases, and the buds go through a transformation from dormant nub to a fully-opened leaf.

The best time to repot is generally in the middle of this process, when the roots are active, and the buds are in the swelling and extending stage. All repotting should be done by the time the trees are in the opening stage.

The tree set to be repotted today is this wonderful crape myrtle (Lagerstroemia indica). The first step is removing the tree from the pot.

Using the root hook and saw, we slowly and carefully create a gap between the root ball and the sides of the pot. Creating this space will allow us to safely remove the tree from the pot.

This tree was certainly in need of being repotted! You can see the abundance of roots on the sides and the bottom of the root ball (below). You can even see where the roots started to grow down through the drainage holes in the pot. These “root plugs” prevent proper drainage, which is very important for tree health.

The frequency of repotting is determined by a number of factors, including species, stage of development, and pot size. Vigorous root growers like maples need to be repotted and root pruned more frequently than pine trees of the same developmental stage (which grow roots more slowly). Though root pruning is important to bonsai health, it can be stressful to a tree if the roots are disturbed too frequently. Knowing the tree species you have and how it grows is important in making the decision of when to repot and root prune.

Using root hooks, scissors, and chopsticks, the roots are teased out and pruned as needed. Cutting the roots back removes large woody roots, allowing more space for fine feeder roots to grow. The woody roots act only as transporters of energy. Woody roots do not absorb water, food, or oxygen; only the fine feeder roots do that. Having primarily fine feeder roots in our pots is what allows us to keep bonsai in such shallow containers. If the woody roots take up too much space, then the tree cannot absorb enough water, food, and oxygen to support the large amounts of foliage they have, and the trees’ health will suffer.

While the tree work is going on, the soil and pot are being prepared for its return.

Bonsai soil is one of the most important aspects of growing bonsai trees. There are many different soil mixes and combinations that can be used based upon your tree species, the region in which you live, the amount of time you have to water, and many other factors. No matter what mix you choose, a good bonsai soil should support vigorous root growth, a healthy microbe balance, and have good drainage. Here at the Chicago Botanic Garden, we use a variety of mixes based on tree species and stage of development. For this tree, we will be using our base mix of akadama (a clay-like material mined in Japan), pumice, and lava rock. Our soil mix is sifted to remove any small particles and dust that could clog up the drainage holes, decreasing drainage.

Once the pot has been cleaned, screens have been secured over drainage holes, and tie-down wires have been added, a layer of lava rock is placed to aid with drainage. After the drainage layer is placed, a small amount of soil is added to bring the tree up to grade and help position it in place.

Once the tree is in place and secured, soil is added and chopsticks are used to push the soil into all the open spaces in and around the root system. Any open gaps left in the pot will result in dead space where roots will not grow. The soil should be firmly in place but not packed too tightly; otherwise, the drainage will be affected, and it will be difficult for roots to grow.

When the soil is set, the tree is soaked in a tub of water and a liquid product called K-L-N, which promotes root growth and reduces stress from the repotting process.

After a good soaking, the tree is removed and allowed to drain, then returned to its bench in the greenhouse. It will remain there until it is warm enough to go outside on the benches. Not all trees are moved to the greenhouse after repotting; most will return to the over-wintering storage. However, this tree was stressed at the end of the growing season, and I wanted to give it a jump-start on the year and give it more time to recover and gain back some of its vigor.

In just a couple of weeks, the tree is fully leafed out, and has had a slight pruning to help balance the new growth throughout all the branches.

This tree is just the beginning of a busy repotting season here at the Bonsai Collection. We will most likely be repotting nearly 100 trees this year—nearly half the collection! Thanks for reading, and be sure to look out for more bonsai blogs to come in the months ahead.

Upcoming bonsai events:

Tropical bonsai are installed in the Subtropical Greenhouse: Tuesday, March 31.

Trees return to the Regenstein Center’s two courtyards for the season: Tuesday, April 22.

Join us May 9 for World Bonsai Day demonstrations, and a tour of the courtyards.

©2015 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org

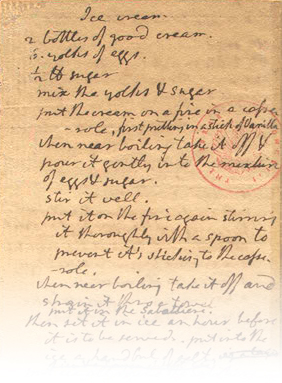

First we learned that one-third of all the ice cream that Americans eat is vanilla.

First we learned that one-third of all the ice cream that Americans eat is vanilla.