One of the most recognized lines from Shakespeare is the following: “Something is rotten in the state of Denmark.” You would have to read Hamlet to get the backstory, but one thing I know as an ecologist, is that we would be in a lot of trouble if there wasn’t a whole lot of rot going on all over the place.

You can probably imagine when walking through our oak woodland, that if things were not constantly rotting, you would be up to your eyeballs in dead leaves, and it would be almost impossible to walk anyway, because of the mass of dead branches and logs lying all over like a bunch of pick-up sticks.

Although there are a tremendous number of organisms that are involved in the rotting process, fungi are the very most important component of this team of decomposers. A tremendous number of species of fungi live in the McDonald Woods at the Chicago Botanic Garden; they can be broken up into two basic categories: those that form symbiotic relationships with living plants (mycorrhizal), and those that decompose organic matter (a.k.a. the rotters).

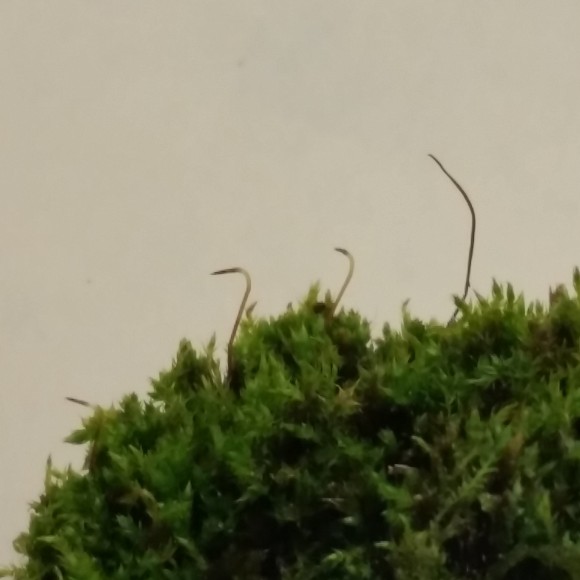

While walking through the woods the other day, I tripped over a downed log and came face-to-face with one member of those decomposers, the bracket fungi. These familiar fungi, also known as shelf fungi, have a characteristic growth form. Most do not produce a stalk (stipe) that supports their cap. Instead, whether on a standing tree or on a log lying on the ground, the cap is attached directly to the wood and projects out horizontally like a shelf or awning.

Gravity causes tropism (the turning or bending in plants and fungi toward or away from an external stimuli), which causes the shelves to orient horizontally out from the wood. This is interesting to observe, especially when a standing dead tree that has shelf fungi falls to the ground, and the new fungi orient in a different direction after the tree falls. (This is one way that you can discover if a tree was dead before it fell to the ground.)

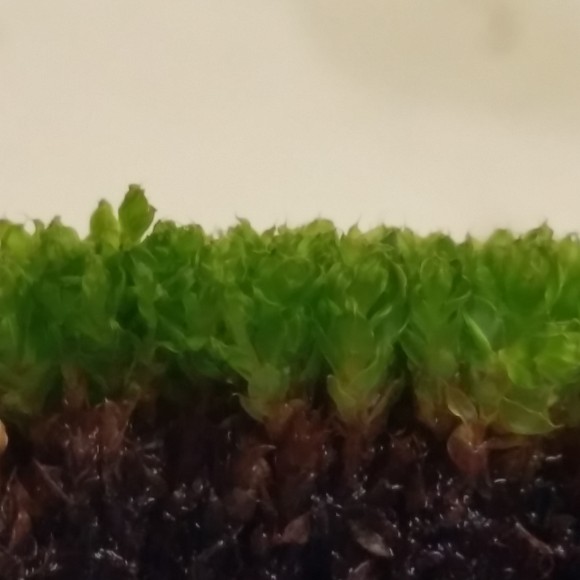

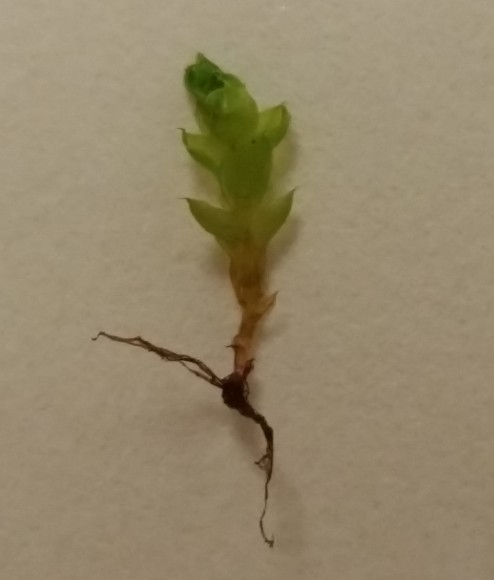

Just like most of the “mushrooms” we find growing on the ground, these shelf fungi are the fruiting bodies of an organism that we seldom see. The actual organism is a spiderweb-like structure that is either sprawled out within the soil or, in the case of the decomposers, spread throughout the dead plant material.

What is important about these decomposer fungi is that they are able to breakdown cellulose and lignin—the building blocks of plants, and two materials that are unable to be decomposed by almost any other organism. Therefore, without the help of these fungi, we would be swimming in a sea of dead plant material, and all those nutrients and minerals would be locked up—unavailable for other plants to use.

Many of the shelf fungi differ from other fungi, not only because of their growth form, but also because they are usually very woody or leathery in nature. ( I can imagine that people mistake some of these fungi for a deformity in the tree when they feel them and realize that they are as hard as a rock. This is not true of all shelf fungi; some are soft and squishy and quite fragile.)

Some common shelf fungi are the artist’s conk (Ganoderma applanatum), the horse hoof fungi (Fomes fomentarius), the turkey tail fungi (Trametes versicolor), and the sulphur polypore (Laetiporus sulphureus).

The type of decomposition that takes place is referred to as either white rot or brown rot. In white rot, the fungi breaks down the lignin and leaves the cellulose behind. Wood that is being decomposed by white rot fungi turns off white and stringy. In brown rot, the fungi decompose the cellulose and leave the lignin behind. Brown rot fungi turn the wood reddish-brown and crumbly. In combination, the two types of decomposers reduce even large tree trunks to their component nutrients and minerals and make them available to the environment for living plants to use.

Although some of the shelf fungi are interesting and quite attractive, like the turkey tail and violet tooth fungi (Trichaptum biforme), it is not a good sign to see them growing on your favorite shade tree. Some of these shelf fungi can be found on living trees where disease or damage has caused the decomposition process to begin, and may not portend a bright future for the tree. You might also see some of the fungi sprouting from structural elements of your home if the wood is unprotected and exposed to excess moisture—another sign of trouble.

Some of the shelf fungi are very prolific and can occur in the hundreds on a single log, or they might be one giant shelf that can be more than a few feet across and weight 50 to 100 pounds or more. One of these large examples can be seen in our Wonderland Express exhibition.

It should also be noted that these shelf fungi have some aspect to them that are of interest other than their role in decomposition: while most species are woody and unpalatable, the chicken of the woods (Laetiporus sulfureus), is considered one of the best fungi for eating. There are also several species of shelf fungi thought to have medicinal properties, including the attractive Ganoderma lucidum (known as reishi in herbal medicine).

So next time you are out hiking in one of our local forest preserves, consider the “shelf life” around you, and what the woods—and life—would be like without them.

Find out more about the natural world at the Garden and in your backyard: learn about Lepidoptera, bats, and grubs.

©2015 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org