Escape to a warmer climate and enjoy a mini-vacation from Chicago winters in the Greenhouses at the Chicago Botanic Garden. Boyce Tankersley, director of living plant documentation, showed us some of the more unusual plants we will find flowering—or fruiting—in the Greenhouses in January.

Click here to view the video on YouTube.

Discover amazing aloes and euphorbias in the Arid Greenhouse:

- We have 43 different species of aloes, including: dwala aloe (Aloe chabaudii), hidden foot aloe (Aloe cryptopoda), and bitter aloe (Aloe ferox). The long tubular flowers of aloes are adapted for pollination by sunbirds, the African equivalent of our hummingbirds. The sap of aloe vera is used widely in cosmetics and to treat burns.

- Our 35 different species of euphorbias are also spectacular during this time period. Look for geographic forms and cultivars of Euphorbia milii as well as the spectacular Masai spurge (Euphorbia neococcinea). Did you know that poinsettias are also in the genus Euphorbia?

- About to flower for only the second time in 30 years is turquoise puya (Puya alpestris), a bromeliad native to the high, dry deserts of Chile whose turquoise flowers are irresistible to hummingbirds.

The Semitropical Greenhouse is where you will find the following:

- Paper flower—What appears to be the “flowers” of Bougainvillea ‘Barbara Karst’ and ‘Singapore White’ are actually colorful bracts surrounding the small, white flowers.

- Dwarf pomegranate (Punica granatum ‘Nana’)—Pomegranates are native to the Middle East and are part of the Biblical Plants collection in the Semitropical Greenhouse.

- Calamondin orange (× Citrofortunella mitis)—This decorative, small orange is too bitter to be eaten.

- Ponderosa lemon (Citrus × ponderosa)—Ponderosa lemons are the largest in the world.

Don’t miss these highlights in the Tropical Greenhouse:

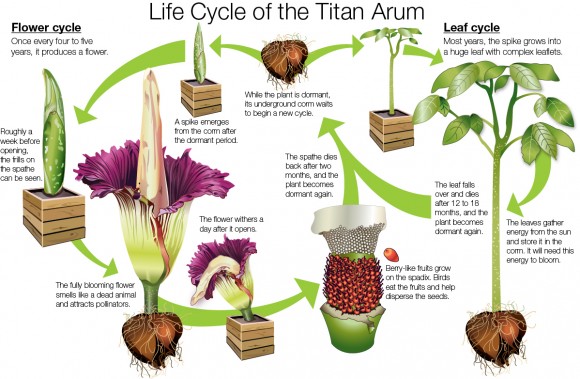

- “Alice” the titan arum (Amorphophallus titanum) with her magnificent orange fruiting spike. (The fruiting stage does not produce an odor.) The fruits will mature over the next two months to a deep red. In the wilds of Sumatra, ripe fruits are eaten by the rhinocerous hornbill, which spread the seeds.

- The vining Vanilla planifolia var. variegata is a variegated form of the Central American orchid that produces vanilla beans

- Cacao (Theobroma cacao)—the pods from this plant are used to make chocolate.

- Nodding clerodendrum (Clerodendrum nutans) is among the first of this genus of winter-flowering shrubs and vines to be covered in showy flowers.

- The elegant white Angraecum Memoria Mark Aldridge orchids with their long nectar tubes signal the start of orchid flowering season.

Please note: The Greenhouses and adjacent galleries will have limited access January 25 – February 7; from February 8 – 12, they will be closed in preparation for the Orchid Show, opening February 13, 2016. From February 13 – March 13, the Greenhouses will be open to Orchid Show ticketed visitors only.

©2016 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org