Last year we discovered Viburnum leaf beetle (VLB) here at the Chicago Botanic Garden for the very first time. As I said then, “I strongly suggest you begin monitoring your viburnums for this critter” as once they move in, they become a perennial pest, just like Japanese beetles.

In early March, we monitored many of the Garden’s viburnums for signs of VLB egg laying and focused on areas where we observed VLB activity last summer. I had read recommendations for pruning out these twigs (with eggs) in the winter as a management technique and wanted to give it a go. To assist with this project, I called in our Plant Health Care Volunteer Monitoring Team; the more eyes the better. The six of us (all armed with hand pruners, sample bags, and motivation) began a close inspection with a focus on last season’s new twig growth for the signs of the distinctive straight line egg-laying sites. In less than five minutes, we found our first infested twig, pruned it out, and put it in a sample bag. After about three hours, we had collected about 20 twigs with eggs.

Truly, I was expecting to find a lot more. This was somewhat disappointing, as I had created a challenge to see which volunteer would fill his or her sample bag and collect the most. This turned out to be more like a needle in a haystack search, as it was a lot more difficult than I had thought. I also feel that the egg-laying sites would have been easier to see if we had done this in early winter, as the egg-laying locations had darkened with time.

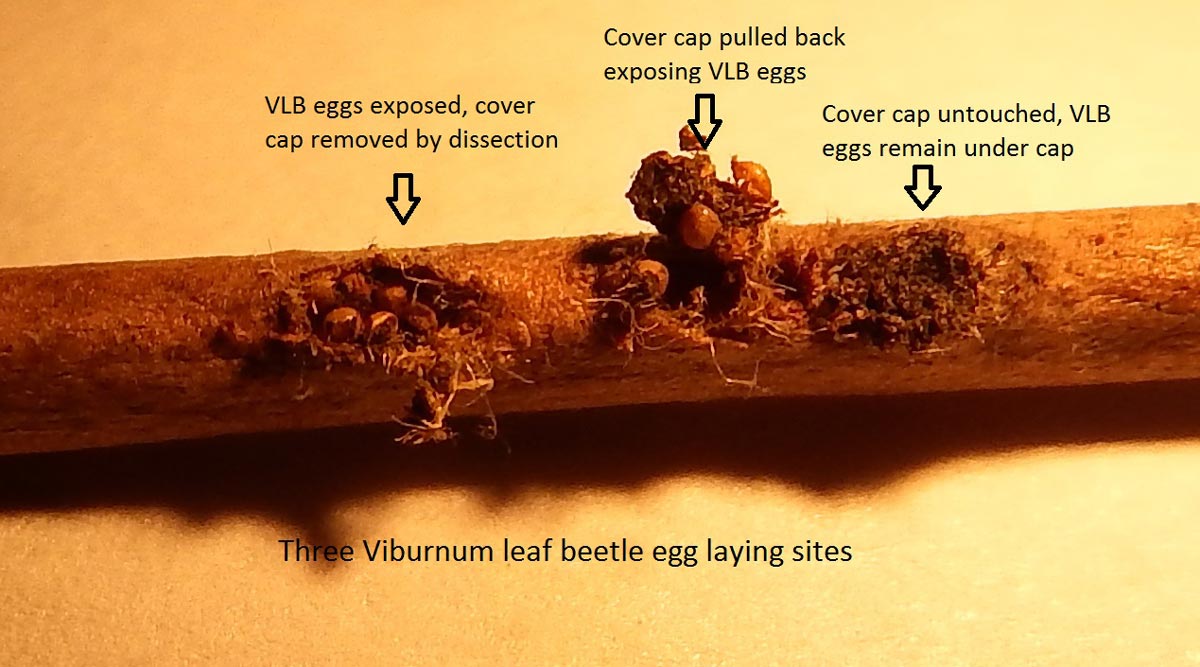

Back at our lab, I dissected some of our samples under the microscope. When I removed the cover cap (created by the female after egg laying) material of a few of the egg-laying locations, I found about six orange, gelatinous balls (the overwintering eggs). These eggs were about a month or two from hatching.

For background on this new, exotic insect pest, please see my June 5, 2015, blog on the Viburnum leaf beetle.

- The favored viburnums are the following:

- Arrowwood viburnum (V. dentatum)

- European and American cranberrybush viburnum (V. opulus, formerly V. trilobum)

- Wayfaringtree viburnum (V. lantana)

- Sargent viburnum (V. sargentii)

- When to monitor and for what:

- In early summer, you would look for the distinctive larva and signs of leaf damage from the larva feeding.

- In mid- to late summer, you would look for the adult beetle and leaf damage from the beetle feeding.

- In the winter, you would look for signs of overwintering egg-laying sites on small twigs.

- Life cycle, quick review:

- In early May, eggs hatch and larva feed on viburnum leaves.

- In mid-June, the larva migrate to the ground and pupate in the soil.

- In early July, the adult beetles emerge and begin to feed on viburnum leaves again, and mate.

- In late summer, the adult female beetle lays eggs on current season twig growth in a visually distinctive straight line.

Hopefully our efforts will lessen the VLB numbers for this coming season. We will see when we monitor the shrubs for leaf damage and larva activity in late May. If nothing else, it was a great learning experience with this very new, exotic insect.

Special thanks to the Plant Health Care Volunteer Monitoring Team: Beth, Fred, Tom (x3), and Chris.

©2016 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org