The Garden’s head of urban agriculture took a trip to Cuba and reminded me of my culture’s resiliency and connection to gardening.

How do you farm when you have little to no resources? Cubans “inventan del aire.”

Literally meaning “inventing from air,” this is the philosophy that is required to get by in Cuba.

Angela Mason, the Garden’s associate vice president for urban agriculture and Windy City Harvest, traveled to Cuba to see firsthand how the farmers there create and maintain collective farms. These farms provide much-needed produce for a population that lives without what we’d consider the basics in the United States. The average hourly wage in the Chicago area is around $24.48. That’s more than the average monthly wage in Cuba.

“Before going, I didn’t understand why people would risk their lives getting on a raft and floating 90 miles,” she said. “But when you see the degree of poverty that some of the people are living in, it’s heartbreaking.”

Angie recounted to me the details of her trip; the people she met, all of whom were welcoming and warm, and the places she saw. She visited several farms just outside of Havana and another in Viñales, in the western part of the country.

Poverty in Cuba means the farmers there grow without supplies and tools that are standard here. But they are still able to create beautiful and sustainable harvests through ingenuity. For example, Angie asked one of the farmers she met what he used to start seeds. He showed her dozens of aluminum soda cans that he’d cut in half. One farmer dug a well by hand. He then used the rocks he dug out to build a terraced garden.

I asked Angie many questions about her trip and what she saw, because I relish every detail I can learn about Cuba, the country where both of my parents were born.

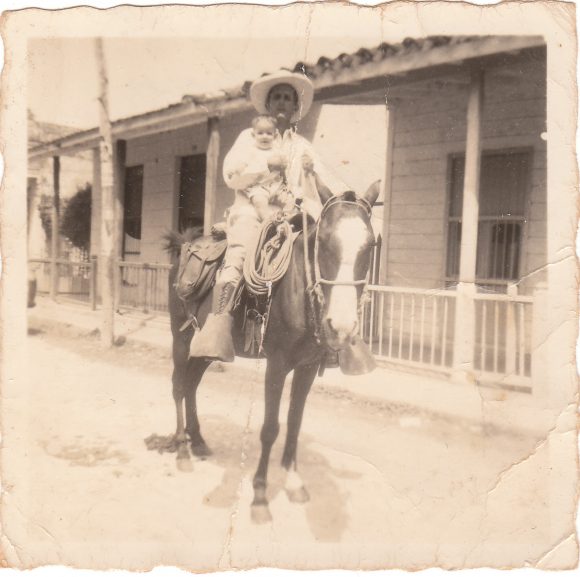

The reasons for Angie’s trip felt especially close to my own family’s heritage, because I come from a long line of farmers on both sides. My mother’s family had a farm in the province of Matanzas. My father’s side did as well, in the more rural province of Las Villas. Both properties have since been seized by the Cuban government, as was all private property after the revolution in 1959. Neither one of my parents has been back to visit since they moved to the United States as children (my father was just a few years old and my mother was 11) so the stories they can share are scarce. The only tangible evidence of childhoods spent in the Cuban countryside are a handful of faded photographs: my mom riding a horse when she was in kindergarten; my father in diapers and running around with farm dogs. And as each year passes, the memories of Cuba are farther and farther in past.

Two of my grandparents, both now deceased, had many stories to share with me as well. My maternal grandfather and my paternal grandmother were fixtures in my life and both often shared stories of their lives before the United States and growing plants and food in the fertile Cuban soil. It’s a talent that apparently never leaves a person, even if they change their country of residence, because both had beautiful backyard gardens at their homes in Miami.

My grandmother had a knack for flowers. The bougainvillea in her yard was always resplendent. Hydrangeas were the centerpieces at my sister’s wedding shower; months later the plant repotted and cared for by my grandmother was the only one that thrived. My grandfather leaned more toward the edible. His yard was full of fruit trees. Whenever he’d visit, he usually brought something growing in the yard: fruta bomba (more commonly known as papaya), mamoncillos, or limon criollo (a type of small green lime).

Growing up, I always associated the cultivation of plants, whether flowers or fruit, as just a part of their personalities. Gardening was a hobby they enjoyed. While that was true, I realized later that it was also an activity that kept them connected to Cuba. As long as they could grow the plants they remembered from back home, that life was not completely gone.

My grandparents, as well as parents, cousins, aunts, uncles, and pretty much most people I’m related to, have all tapped into their resiliency to make it as immigrants in the United States and adapt to their changed lives. The same personality trait that allows a Cuban farmer to grow vegetables without any tools has gotten my family through decades of living outside of Cuba. No matter the situation, members of the Cuban diaspora “inventan del aire.” It’s how people survive in Cuba, but it’s also how Cubans outside of the country get through exile.

©2016 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org