Dr. Evelyn Williams is an adjunct conservation scientist at the Garden. She’s interested in genetic diversity at multiple scales, from the population to the family level. While at the Garden, Dr. Williams has worked on rare shrubs from New Mexico (Lepidospartum burgessii), systematics of the breadfruit family (Artocarpus), and using phylogenetic diversity to improve tallgrass prairie restorations.

Dr. Evelyn Williams is an adjunct conservation scientist at the Garden. She’s interested in genetic diversity at multiple scales, from the population to the family level. While at the Garden, Dr. Williams has worked on rare shrubs from New Mexico (Lepidospartum burgessii), systematics of the breadfruit family (Artocarpus), and using phylogenetic diversity to improve tallgrass prairie restorations.

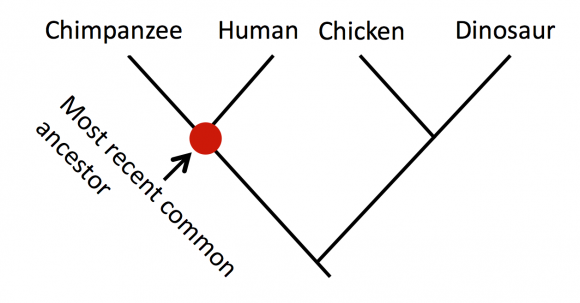

When a scientist says that chimpanzees are related to humans, or that chickens are related to dinosaurs, what do they mean?

They mean that chimpanzees and humans share a common ancestor from many thousands of generations ago. Although that shared great-great-great-great-(etc.)-great-parent lived many years ago, that shared ancestor lived more recently than the ancestor that humans share with dogs. So humans are more closely related to chimpanzees than dogs because they have the most recently shared ancestor. Scientists call this the “most recent common ancestor.”

This most recent common ancestor wasn’t a chimp, and it wasn’t a human—it was a different species with its own appearance, habits, and populations. One of these populations evolved into humans, and one of the populations evolved into chimpanzees. We know this because of a field of study called “phylogenetics.” Scientists use phylogenetics to study how species are related to each other.

Using DNA sequences, scientists construct tree-like diagrams that trace how species are related. A human’s DNA is more similar to a chimpanzees’ than to a chicken, so a tree diagram would connect humans and apes. Dinosaurs and chickens would be shown as related as well, and then these two groups would be connected.

Interested in learning more? Explore phylogenetics with the Tree of Life Web Project. Dig deep into the study of the phylogenetic roots of food plants with The Botanist in the Kitchen.

Students in the Chicago Botanic Garden and Northwestern University Program in Plant Biology and Conservation were given a challenge: Write a short, clear explanation of a scientific concept that can be easily understood by non-scientists. This is our fourth installment of their exploration.

©2016 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org