Alice the Amorphophallus, our titan arum (or corpse flower) is fruiting! Alice is on display at a new location in the Tropical Greenhouse here at the Chicago Botanic Garden so that all of our visitors may come see the beautiful, dark orange fruit that is developing.

As many of you know, we manually pollinated Alice’s flowers on the morning of September 29, 2015, after the plant began blooming late the previous evening. We used the pollen we had collected from Alice’s “brother” Spike a month earlier, plus pollen from the Denver Botanic Gardens’ bloom, Stinky (in the same bloom cycle as Spike). About half of the developing fruits are from Spike’s pollen and the other half are from Stinky’s pollen.

It can take five to six months for the fruit to ripen, and the fruiting process is quite beautiful to observe, as the fruits change from a gold color to orange, and finally to a dark red color once ripened. After the 400+ fruits are ripe, we will harvest the fruits, and extract the two seeds that are produced by each fruit. We hope to germinate a few of these seeds in order to grow more titan arums to add to our collection—and increase the age diversity of the collection as well. (As many of our current plants have the same seed or corm source, they are all roughly the same age.) Some of the seeds will be shared and distributed to other botanical gardens, universities, and educational institutions as requested. The rest of the seeds harvested will be stored in our seed bank freezer in the Daniel F. and Ada L. Rice Plant Conservation Science Center. This will help with increasing the genetic diversity of the species and continue to aid with plant conservation efforts.

I realize there are many questions that you may have regarding Alice’s fruit, many of which were asked during the time that Alice (and Spike) were on display last year.

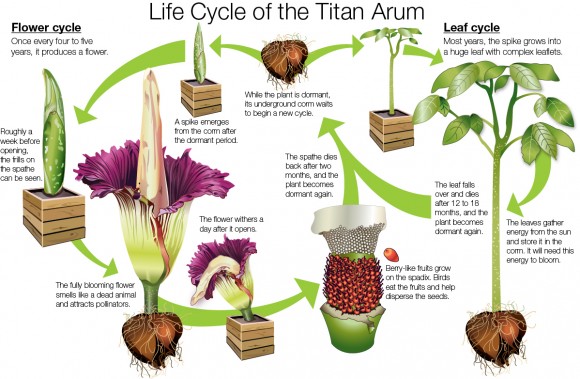

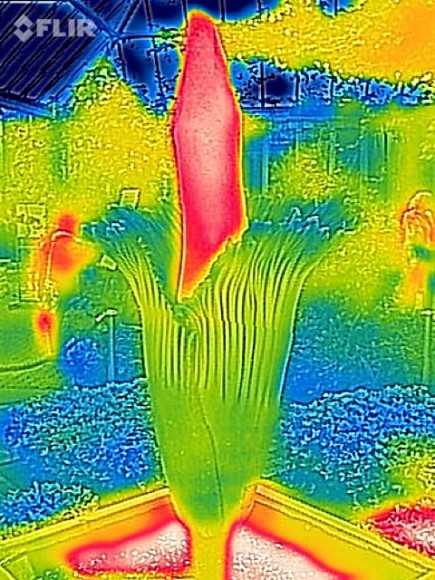

The titan arum is the largest non-branched inflorescence in the world, and it is found in the dense jungles of Sumatra. An inflorescence is a cluster of flowers—like a bouquet. The inflorescence of the titan arum is composed of two parts: The outer, purple, vase-like sheath (a single leaf) is called the spathe. It protects the inner tube-like spike called the spadix, which attracts pollinators. The flowers are small and are located on the base of the spadix. There are hundreds of them.

The titan arum is the largest non-branched inflorescence in the world, and it is found in the dense jungles of Sumatra. An inflorescence is a cluster of flowers—like a bouquet. The inflorescence of the titan arum is composed of two parts: The outer, purple, vase-like sheath (a single leaf) is called the spathe. It protects the inner tube-like spike called the spadix, which attracts pollinators. The flowers are small and are located on the base of the spadix. There are hundreds of them.

What does it mean that Alice is producing fruit?

The fruiting process of a titan arum is just like that of other flowering plants. After a flower is pollinated, the fleshy fruit develops (think of a cherry or apricot). The fruits of the titan arum grow from a yellow-gold to a more orange-red tone. When the fruit is fully ripened, about six months after pollination, it will have a soft outer flesh that is dark red in color. After fruiting, the plant will return to dormancy, and send up a leaf in its next growth cycle.

Does Alice still smell?

No. Alice is not producing any odor and it is not blooming. Odor is only produced within the first 24–48 hours during the initial bloom. After flowering, Alice’s spathe shriveled and dried out, and was removed one week after the initial bloom. The spadix began to collapse five days after pollination; it was removed two months later after it was completely dried up.

Will Alice bloom again?

Yes, but not in the near future. After the fruits mature, the plant will go dormant for a period of time, then produce a new leaf every year for a number of years. Once the corm’s energy has been replenished, Alice will bloom again. However, we now have 13 titan arums in the Garden’s collection, and we expect that another will bloom within the next year or two. We do not know when, as it is hard to predict—even in nature. The plant needs to recover and build up energy before it can flower again.

What did you do with pollen from Alice?

Garden conservation scientists collected pollen from Alice during her bloom. Several small holes were cut in the spathe for manual pollination to take place. The same access holes were used to collect pollen later in the day. The pollen is now in cold storage to use in pollinating the next titan arum bloom at the Garden. We also share pollen with other botanic gardens, universities, and educational institutions.

Today, the Garden has 13 titan arums in its collection. But the increase in number is not the result of pollination. Just like many of our spring bulbs (such as narcissus, canna, and dahlias), the tuber, or bulb, that produces the flower for the titan arum grew additional bulbs that we hope will produce fully-grown plants.

In nature, the fruit is eaten by the rhinoceros hornbill (Buceros rhinoceros). Attracted by the brightly colored covering, the birds eat the fleshy fruits and excrete the hard, resistant inner seeds. The fruit is not suitable for human consumption.

What does the titan arum look like before it blooms?

This plant produces one leaf at a time for several years. The leaves start out small and get progressively larger each year. We have several in our production area now. The leaves photosynthesize and allow the plant to store energy in a large (sometimes weighing up to 40 pounds) underground tuber called a corm. Each leaf lasts about a year before it dyes back and goes dormant. Because flowering takes so much energy, it takes several years before the plant has enough energy stored to produce a flower. Alice took 12 years to come to flower!

Come out and see Alice and her fruit now through April 8, 2016. To learn more about Alice and Spike, read our previous blog posts!

©2016 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org

![ILLUSTRATION: Bud shown with male and female flowers of Amorphophallus titanum (Becc.) Becc. - Titan Arum from Curtis’s Botanical Magazine, vol. 117 [ser. 3, vol. 47]: t. 7153 (1891) [M. Smith].](https://my.chicagobotanic.org/wp-content/uploads/corpse-plant-bud-and-flowers-348x580.jpg)