Rick Overson is fascinated with insects—especially the kinds that love desert climates like in Arizona, where he grew up and earned his Ph.D. in biology. After completing a postdoctoral assignment in northern California, he decided it was time to get to know the little buggers even better, so Dr. Overson hopped on a plane for Chicago and stepped out into the subzero temperatures of the polar vortex to do just that.

The devoted entomologist didn’t expect to see the insects in Chicago, but he was eager to join research at the Chicago Botanic Garden. A multidisciplinary team was assembling there to look for scent variations within Onagraceae, the evening primrose family, and connections from floral scent to insect pollinators and predators. The findings could answer questions about the ecology and evolution of all insects and plants involved. Overson is a postdoctoral researcher for the initiative, along with Tania Jogesh, Ph.D.

“Landscapes of Linalool: Scent-Mediated Diversification of Flowers and Moths across Western North America” is funded by a $1.54 million Dimensions in Biodiversity grant from the National Science Foundation. The project is headed by Garden scientists Krissa Skogen, Ph.D., Norman Wickett, Ph.D., and Jeremie Fant, Ph.D. It was developed from prior research conducted by Dr. Skogen on scent variation among Oenothera harringtonii plants in southern Colorado.

“For me, the most important thing coming out of this project is documenting and showing this incredible diversity that happens inside a species,” said Overson. “It’s vitally important for me to break down this idea of a species as a discrete unit. It’s a dynamic thing that is different in one place than another. That factors into conservation and our understanding of evolution.” In this case, he and his colleagues theorize that the evolution of the insect pollinators and predators is connected to the evolution of the scent of the plants.

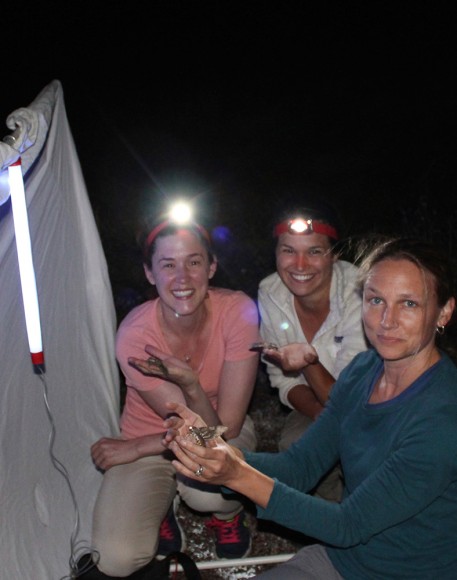

The first two years of field work brought Overson back to his desert home. He traveled across Arizona, Utah, and nearby states with a group of about five scientists during summer months when the flowers were blooming. The team visited several populations each of 16 species of flower for a total of 60 locations. Overson and the team identified and documented the insects visiting the plants and compiled scent chemistry from the flowers. Their tool kit included a pump to pull the scent from a flower onto tiny polymer beads that held the scent inside of a vial. From there, they extracted the scent chemicals at the end of the research day or night. “It’s definitely the case that this pattern of scent variation inside a species is very common in this group,” he said of the team’s preliminary findings.

In the field they also took video recordings of pollinator behavior to see who visited which flowers and when. The pollinators, including hawkmoths and bees, follow scents to find various rewards such as pollen or nectar. The insects are selective, and make unique choices on which plants to visit.

Why do specific pollinators visit specific plants? In this case, the Skogen Lab is finding that it is in response to the scent, or chemical communication, each flower releases. “In the natural world those [scents] are signals, they are messages. Those different compounds that flowers are producing, a lot of them are cocktails of different types of chemicals. They could be saying very different things.”

A destructive micromoth called a microlepidopteran (classified in the genus Mompha), has also likely learned how to read the scent messages of its hosts. The specialist herbivore lays eggs on plants leading to detrimental effects for seed production. The team’s field work has shown that Mompha moths only infect some populations of flowers. When and why did the flowers evolve to deter or attract all of these different pollinators? Or was it the pollinators who drove change?

At the Garden, Overson is currently focused on exploring the genomes, or DNA set, of these plants to create a phylogeny, which looks like a flow chart and reads like a story of evolution. “Right now we don’t know how all of these species are interrelated,” he explained. When the phylogeny is complete, they will have a more comprehensive outline of key relationships and timing than ever before. That information will allow scientists to determine where specific scents and other traits originated and spread. He will explore the evolution of important plant traits using the phylogeny including the color of the flowers and their pollinators, to answer as many questions as possible about relationships and linked evolutionary events.

In addition, the team is looking at population genetics so they can determine the amount of breeding occurring between plant locations by either seed movement or by pollinators. They will also look for obstacles to breeding, such as interference by mountain ranges or cities.

“Relationships among flowering plants and insects represent one of the great engines of terrestrial diversity,” wrote principal investigator Krissa Skogen, PhD, in a blog post announcing the grant.

The way that genes have flowed through different populations, or have been blocked from doing so over time, can also lead to changes in a species that are significant enough to drive speciation, or the development of new species, said Overson. “The big idea is that maybe these patterns that are driving diversity within these flowers could ultimately be leading to speciation.”

By understanding these differences and patterns, the scientists may influence conservation decisions, such as what locations are most in need of protection, and what corridors of gene flow are most important to safeguard.

“We absolutely can’t live without plants or insects, it’s impossible,” remarked Overson. “Plants and insects are dominant forces in our terrestrial existence. Very few people would argue that we haven’t heavily modified the landscape where these plants and insects live. I think it is crucially important to understand these interactions for the sake of the natural world, agriculture and beyond.”

When Dr. Overson is taking a break from the laboratory, he visits the Desert Greenhouse in the Regenstein Center, which feels like home to him.

©2016 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org