Experts in reforestation are concerned with the reasons why some replanted sites struggle. They suspect the problem may be solved through soil science.

The health of a forest is rooted in soil and the diverse fungi living within it, according to researchers at the Chicago Botanic Garden, Northwestern University, and collaborators at China’s Central South University of Forestry and Technology.

In densely populated places such as the Chicago area and Changsha, the capitol of the Hunan province, ongoing development and urban expansion frequently lead to the deforestation of native natural areas.

“There has been a lot of deforestation in China and so there is interest in knowing how best to do reforestation, whether we’re using native plants or introduced plants in plantation settings,” explained Greg Mueller, Ph.D., chief scientist at the Garden. “Understanding who the players are both above ground and below ground helps us understand the health and sustainability of that above-ground plant community,” he added. “It’s analogous to restoration work being carried out here in the Midwest.” The climate, he explained, is similar in Changsha and Chicago.

A wide variety of fungi live in a symbiotic partnership with roots of trees everywhere. These fungi and trees are involved in a vital exchange of goods. The fungi deliver water and nutrients to the trees, and in return take sugars the trees produce during photosynthesis. Without this symbiotic relationship, the system would fail.

Not all tree species and fungi can team up for success, according to Dr. Mueller, who explained that it is essential for the partners to be correct if the tree is to survive. “The wrong fungi may actually be more pathogenic than beneficial,” he explained. Mueller is guiding research on this delicate soil-tree relationship as conducted by his doctoral student Chen Ning.

Ning is on leave from his position as a lecturer at Central South University of Forestry and Technology while he completes his studies with the Garden and Northwestern University. However, much of his work is taking place in China, where he has just completed the first phase of fieldwork.

After completing his master’s degree, Ning was keenly aware of the important role fungi play in the health of the natural world. He knew that he “wanted to ask some questions about the environment and how fungi influence the environment.” He added with a smile, “that’s why I chose to do some dirty work in the soil.”

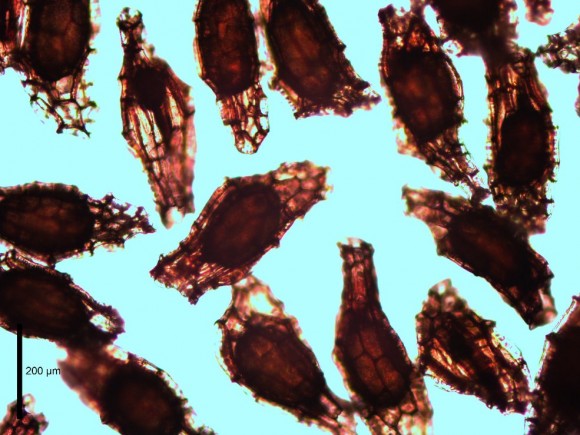

The bright scientist is using the latest technology available, next-generation sequencing, to examine the molecular composition of soil samples taken from locations where native or nonnative trees or both were replanted 30 or 40 years ago. Specifically, he is looking at the replanting of Mason pines, a native Chinese pine, and slash pine (Pinus ellitottii), a nonnative pine introduced to China from the tropical state of Florida.

Ning recently completed his first review of those samples, finding large numbers of fungi in each. In addition, he found that the three different habitats have very different fungal communities.

Mueller and Ning visited the university and collaborators in Changsha in February. Mueller was able to visit the sites Ning sampled during the first phase of research and see the setup for the second phase of research in the greenhouses. The level of disturbance in the natural areas was extensive, a point of interest for Mueller who said, “that again makes it interesting to look at some ecological questions about disturbance and how that impacts these systems.” The team also had time to discuss the importance of considering fungi in related research initiatives.

Next up, Ning will examine his greenhouse plantings that use soils taken from his different field sites to determine if the fungi community changes in response to what type of tree is planted. When that is complete at the end of this summer, Ning will look at the enzyme activity in the soil to determine if fungi are functioning differently in the three different plantings (native forest, native tree in plantation, exotic tree in plantation). The study is on a fast track with a targeted completion date in late 2017 and is expected to add new understandings to the biology of plant-fungal relationships while generating important information on reforesting disturbed sites in south-central China.

After completing his Ph.D., Ning hopes to work as a professor to inspire students in China to pursue similar research. He also aspires to serve as a bridge between the United States and China for new research collaborations on topics such as climate change in order to help figure out the ‘big picture’ in the future.

©2016 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org