Garlic is so easy to grow that the instructions could be just one sentence long:

In October, separate a large head of garlic into individual cloves, and plant 3–4 inches deep in well-amended, well-drained, and well-mulched soil until harvest next July.

But let’s dig a little deeper into that sentence for a few tips on growing a gorgeous garlic crop.

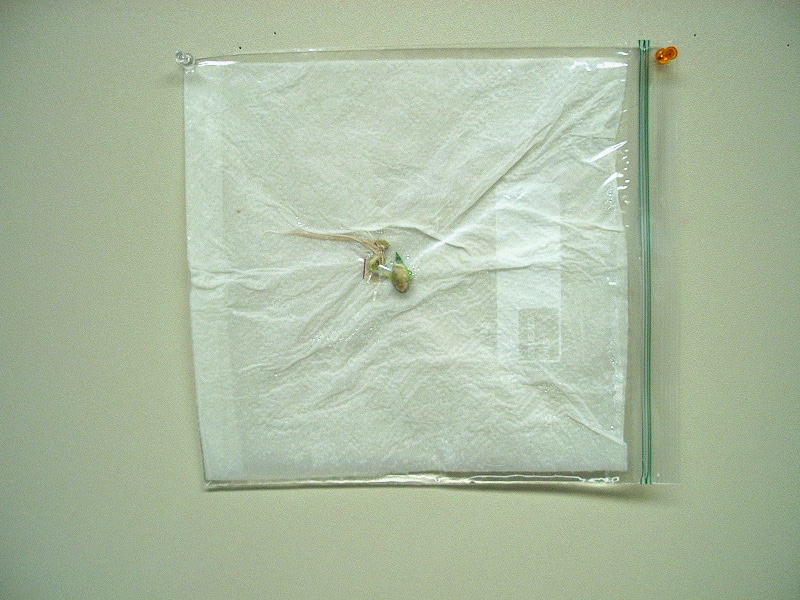

In October… Fall is the season for planting garlic in our area. Wait until the first light frost to plant, and don’t worry if you see a few garlic sprouts popping up before winter sets in.

…separate a large head of garlic… Which garlic to plant? Experiment with different varieties to find the flavor you like best. Nurseries and seed catalogs offer seed garlic (grocery store-bought garlic isn’t as reliable as seed). There are two main types:

- Hard-necked varieties grow well in northern climates like ours, where winter is cold and spring is long. As the name implies, hard-necks produce a rigid flower stalk or “scape” with aerial bulbs. The scape should be cut off at about 10 inches long so that the plant continues to put its energy into the underground bulb. Don’t toss the scapes—eat them, instead, in soups, sautés, etc. ‘Music’, ‘German Extra Hardy’, and ‘Chesnok Red’ are hard-neck varieties known for their wonderful, complex flavors.

- Soft-necked varieties don’t produce scapes; their soft foliage can be braided for easy hanging/storage. While soft-necks flourish in the South, some varieties, such as ‘Inchelium Red’, can be successfully grown here.

…into individual cloves… To grow the largest garlic heads, plant only the largest garlic cloves, and leave the papery “tunic” intact. Cloves can rot without their protective tunic! Hard-necked garlic heads yield large cloves in small numbers (often 4–6), while soft-necked garlics bear more numerous cloves, often in several layers.

…and plant 3–4 inches deep… Plant cloves roots down, points up, about 6–8 inches apart.

…in well-amended… Soil prep is key to a successful crop, no matter what type of soil you have. Garlic is a heavy feeder, so the soil needs to provide plenty of nutrients, air, and water. Amend your soil with compost or well-aged manure until it feels loose and airy. Aim for a neutral pH of 6.5.

…well-drained… While it needs to be kept watered, it is important to plant it in a spot where the soil is moist, but not too wet. Garlic doesn’t like “wet feet.” Once foliage appears in spring, water consistently (about 1 inch per week) until two weeks before harvest in July.

…and well-mulched soil… After a hard frost, cover the garlic bed loosely with a thick layer of mulch (about 6 inches of straw, leaves, and/or grass clippings). Mulch acts like a blanket over the bulbs and soil, holding in moisture and keeping down weeds, which can easily overwhelm and outcompete garlic. Leave mulch intact through the season—garlic sprouts will make their way through it—but remove it when things warm up in the spring.

…until harvest next July. In July, garlic foliage begins to turn brown, signaling that harvest is near. Wait until just five green leaves are left on the plant. Then use a pitchfork to gently loosen the soil beneath the bulbs and bring them to the surface. Resist the urge to pull them by their stalks, taking care not to damage the papery tunic! Brush off most of the dirt, then allow your harvest to cure:

- Spread out the bulbs (with foliage intact) on screens, or tie them in loose bundles and allow to dry in a shady, well-ventilated area, such as a back porch or garage.

- Do not wash the bulbs to remove soil! Leave them undisturbed for 4–6 weeks, during which time they’ll dry out completely.

- After curing, trim the roots and cut stalks to about 1 inch from the bulb.

Many of these same cultural practices follow for shallots and other allium varieties.

One last tip: Store your garlic at 50 to 70 degrees—but not in the refrigerator, as cold makes bulbs sprout early! With proper curing and storage, your bulbs should last about four months.

©2013 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org