It’s that time of year again—time for student science fair projects. Many students I know struggle to find a good idea, and sometimes wait until the last minute to do their experiments. We in the Education Department of the Chicago Botanic Garden are committed to helping make science fair a painless and even fun learning experience for students, parents, and teachers by offering some simple ideas for studying plants.

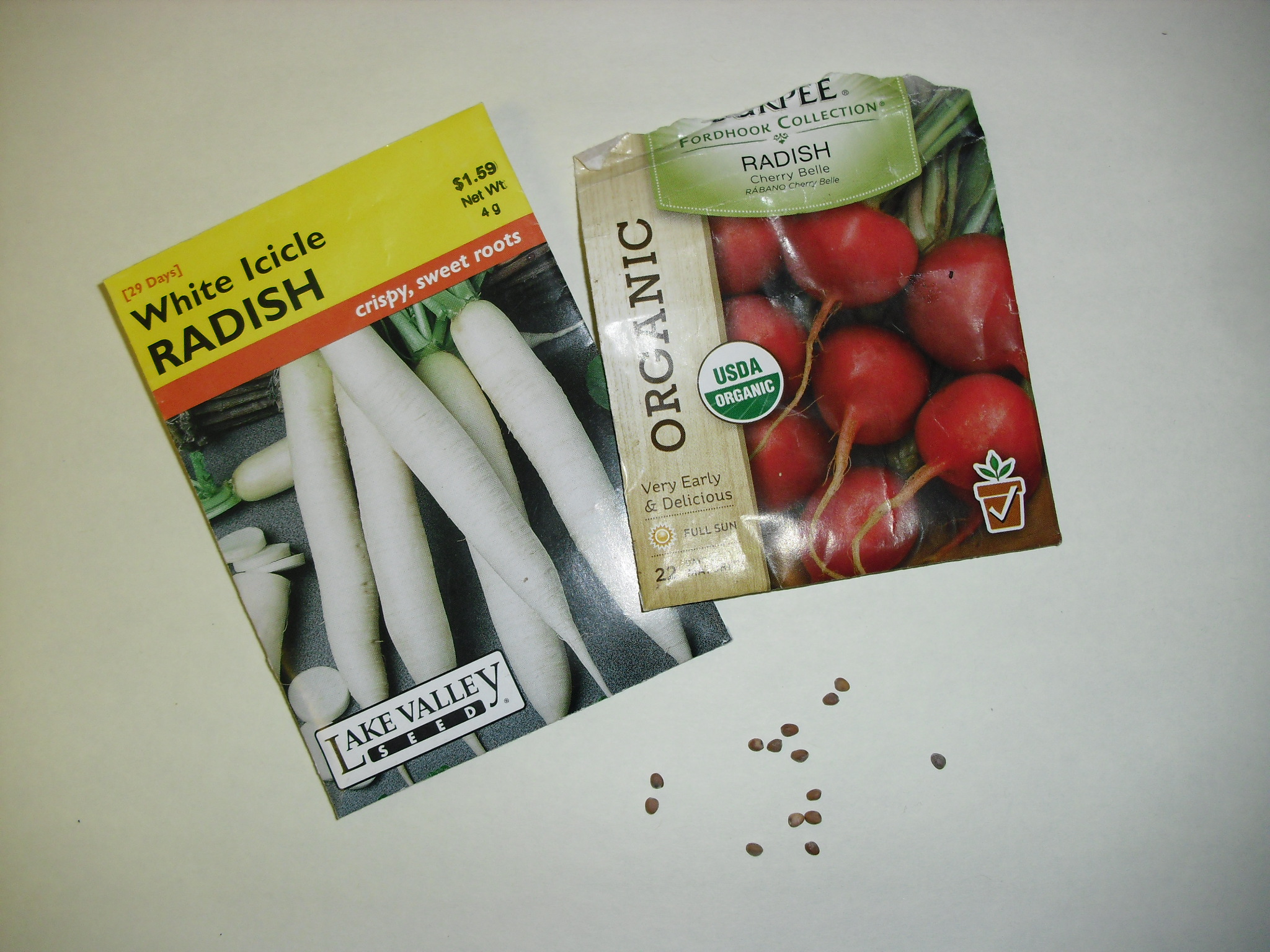

A no-brainer botany project is testing germination of radish seeds in different conditions. Radish seeds are easy to acquire, inexpensive, large enough to see and pick up with your fingers, and quick to germinate under normal conditions. Testing germination does not take weeks, doesn’t require a lot of room, and is easy to measure—just count the seeds that sprout!

To set up a seed germination experiment, use this basic procedure:

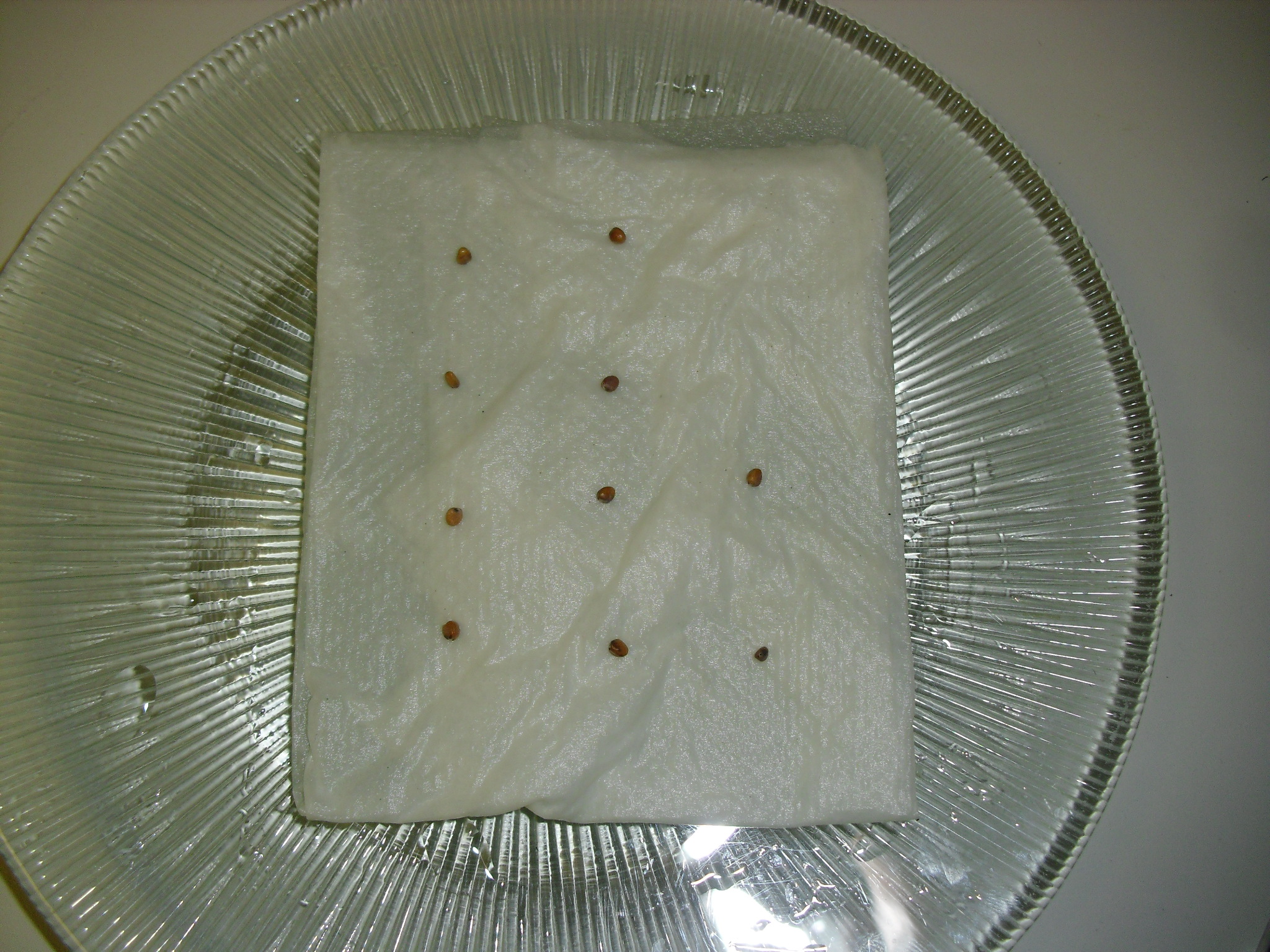

- Gather three or more small plates, depending on how many ways you will be treating your seeds.

- Place a folded wet paper towel on the plate.

- Place ten seeds on the wet paper towel. You can use more seeds—the more you have, the more reliable your results will be—but using multiples of ten makes it easier to calculate percentages.

- Cover with a damp paper towel; label the plates.

- Treat the seeds the same way in every respect except for one thing: the condition you are testing. That condition is your “independent variable,” which may also be called the “experimental variable.” No matter what you are testing, one plate should be set up with the basic directions and no treatment. That plate is the “control” that all the other plates can be compared with.

- When the seeds sprout root and leaves, remove the top paper towel. Compare the number of seeds that germinate and the time it takes for seeds in each condition. You should be able to wrap this up in less than a week.

Now all you need are some ideas for conditions to test. Here are eleven questions you can investigate at home or school using the same basic proceedure:

1. Do seeds need light to germinate?

Place your plates of seeds in different light conditions: one in no light (maybe in a dark room or a under a box), one in indirect/medium light (in a bright room, not near the window), and one in direct light (by a south-facing window). Compare how well the seeds germinate in these conditions.

2. Do seeds sprout faster if they are presoaked?

Soak some seeds for an hour, a few hours, and overnight. Place ten of each on a germination plate, and and compare them with ten dry seeds on another plate.

3. Does the room temperature affect germination rate?

You’ll need a thermometer for this one. Place seed plates on a warming pad, in room temperature, and in a cool location. Monitor temperature as well as germination rate. Try to ensure that the seeds have the same amount of light so it’s a fair test of temperature and not light variation.

4. Do microwaves affect germination?

Put seeds in the microwave before germinating and see if this affects them. Try short bursts, like one and two seconds as well as ten or 15 seconds, to see if you can determine the smallest amount of radiation that affects seed germination.

5. Does pH affect germination rate?

Wet the paper towels with different solutions. Use diluted vinegar for acidic water, a baking soda or mild bleach solution for alkaline conditions, and distilled water for neutral.

6. Does prefreezing affect the seed affect germination?

Some seeds perform better if they have been through a cold winter. Store some seed in the freezer and refrigerator for a week or more before germinating to find out if this is true for radishes or if it has an adverse affect.

7. Does exposure to heat affect germination rate?

Treat your seeds to heat by baking them in the oven briefly before germinating. See what happens with seeds exposed to different temperatures for the same amount of time, or different amounts of time at the same low temperature.

8. How is germination rate affected by age of the seeds?

You can acquire old seeds from a garden store (they will be happy to get rid of them), or maybe a gardener in your family has some old seeds hanging around. Find out if the seeds are any good after a year or more by germinating some of them. Compare their germination rate to a fresher package of the same kind of seed.

9. Do seeds germinate better in fertilized soil?

Instead of using the paper-towel method, sprout seeds in soils that contain different amounts of Miracle-Gro or another soil nutrient booster.

10. Does scarification improve germination rate?

Some seeds need to be scratched in order to sprout—that’s called “scarification.” Place seeds in a small bag with a spoon of sand and shake for a few minutes and see if roughing them up a bit improves or inhibits their germination.

11. Does talking to seeds improve their germination rate?

Some people claim that talking to plants increases carbon dioxide and improves growth. Are you the scientist who will show the world that seeds sprout better if you read stories to them? Stranger discoveries have been made in the plant world.

That eleventh idea may seem silly, but sometimes science discoveries are made when scientists think outside the seed packet, so to speak. Students should design an experiment around whatever question interests them—from this list or their own ideas—to make the research personal and fun. As long as students follow the scientific method, set up a controlled experiment, and use the results of the experiment to draw reasoned conclusions, they will be doing real science. The possibilities for botanical discovery are endless, so get growing!

©2013 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org