In a first-time summer internship research project, two college students set out to understand how plants were responding to the Garden’s shoreline restoration projects. They took a deep look into how variations in water levels may be affecting the health of the young plants. The results of their work will help others select the best plants for their own shorelines.

A silent troop of more than one-half million native plants stand watch alongside 4½ miles of restored Chicago Botanic Garden lakeshore. The tightly knit group of 242 taxa inhibit erosion along the shoreline, provide habitat for aquatic plants and animals, and create a tranquil aesthetic for 60 acres of lakes.

Now ranging from 2 to 15 years old, the plants grow up from tiered shelves on the sloping shores. Species lowest on the slope are always standing in water. At the top of the slope, the opposite is true, with only floods or intense downpours bringing the lake level up to their elevation.

Wading In

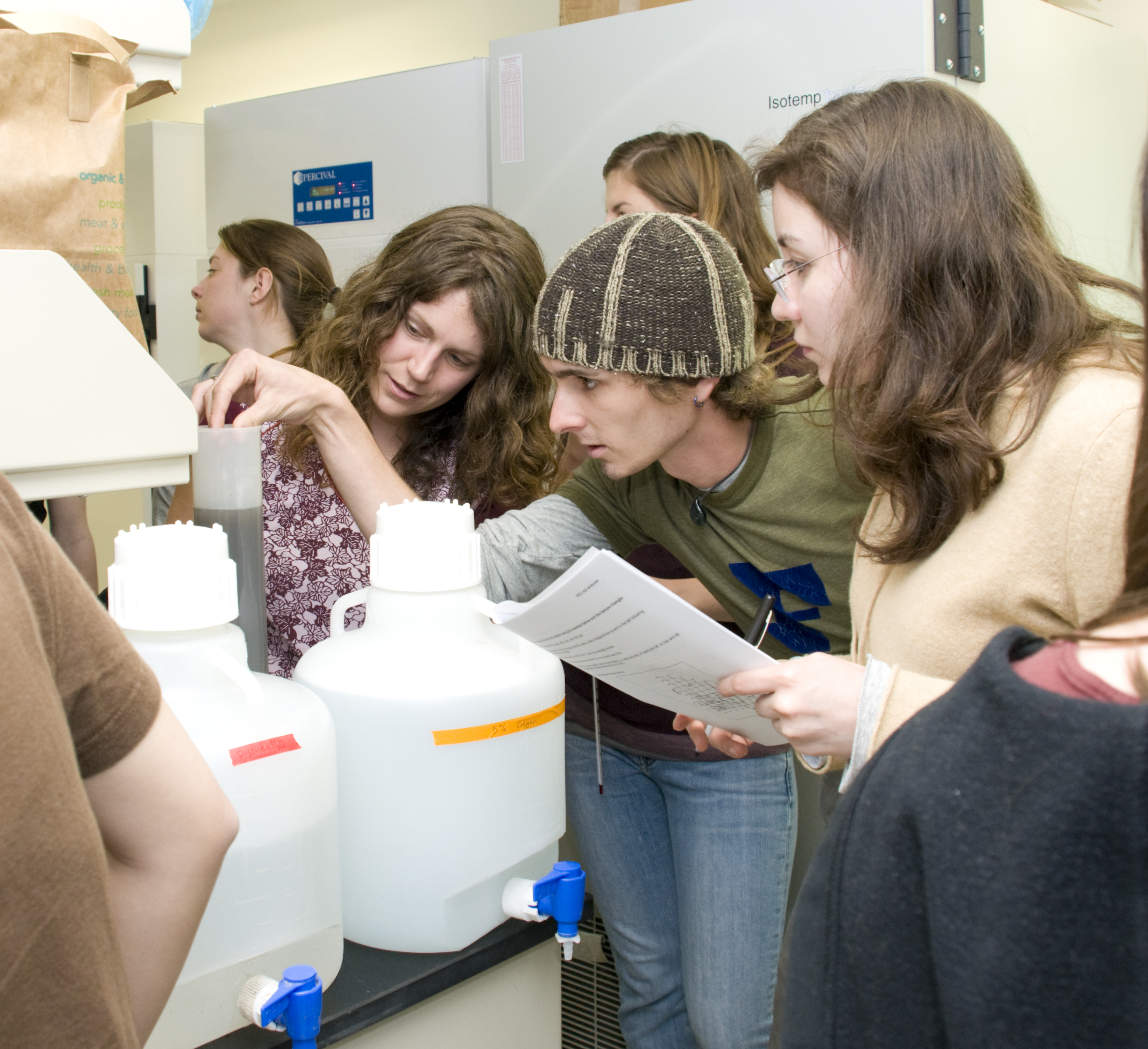

Jannice Newson and Ben Girgenti moved through clusters of tightly knit foliage along the Garden shoreline from June through August, taking turns as map reader or measurement taker. On a tranquil summer day, one would step gingerly into the water, settling on a planting shelf, before lowering a 2-foot ruler into the water to take a depth measurement. The other, feet on dry land, would hold fast to an architectural map of the shoreline while calling out directions or making notes.

Newson, a Research Experiences for Undergraduates (REU) intern and sophomore at the University of Missouri, and Girgenti, a Garden intern and senior at Brown University, worked under the guidance of Bob Kirschner, the Garden’s director of restoration ecology and Woman’s Board curator of aquatics.

When the summer began, Girgenti and Newson had hoped to locate and measure every single plant. But after the immense scope of the project became clear in their first weeks, they decided to focus on species that are most commonly used in shoreline rehabilitation, as that information would be most useful for others.

View the Garden’s current list of recommended plants for shoreline restoration.

“We’re interested in which plants do really badly and which do really well when they are experiencing different levels of flooding, with the overall idea of informing people who are designing detention basins,” explained Girgenti, who went on to say that data analysis of the Garden’s sophisticated shoreline development would be especially useful for others.

“The final utility of this research will be to inform other natural resource managers,” confirmed Kirschner, who added that successful Garden shoreline plants must be able to withstand water levels that can rise and fall by as many as 5 feet several times in one year.

Steering the Ship

Along the shoreline, the interns followed vertical iron posts that were installed as field markers during construction, in order to find specific plants shown on the maps. “The posts are pretty key to being able to map out the beds,” said Girgenti.

Once they found a target plant, they then counted clumps of it, and put it into one of six categories based on the amount of current coverage, ranging from nonexistent to area coverage of more than 95 percent.

They also measured the average depth of water for beds with plants below the water line, noting their elevation. For plants above the water line, the elevation was derived from the architectural drawings.

Data about the elevation and coverage level of each measured plant, together with daily lake water level readings dating back to the late 1990s, was then entered into a spreadsheet and prepared for analysis to identify correlations between planting bed elevation and plant survival.

Beneath the Surface

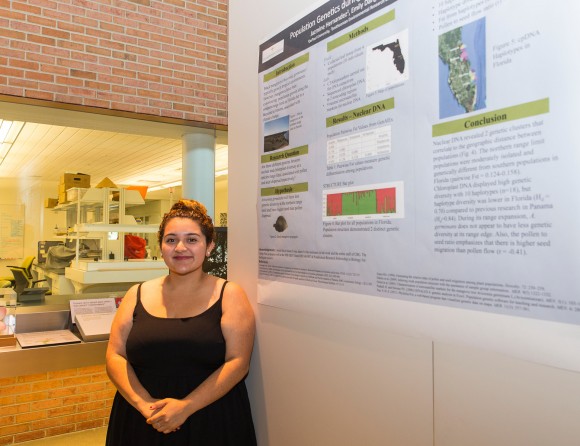

For her REU research project, Newson was careful to collect data for one species in particular, blue flag iris. “As a preliminary test of the project hypothesis, data relating to 101 planting beds of Iris virginica var. shrevei were analyzed to see if there was a significant correlation between the assessed plant condition and each planting bed’s elevation relative to normal water,” she explained in her final REU poster presentation in late August.

An environmental science major, she initially experienced science at the Garden as a participant in the Science First Program, and then as a Science First assistant, before becoming an REU intern.

Girgenti began his Garden work in the soil lab, where his mentor inspired him to focus on local, native flora. “I was kind of pushed up a little bit by the Garden,” he said. The following year he did more field work in the Aquatics department. “I wanted to come back because I really enjoyed being here the last two years,” he said. “Every year I’ve come back to the Garden, I’ve been very excited about what I’m going to do.”

Aside from the scientific discovery, the two also refined their professional interests. “I do enjoy being out in the field as opposed to maybe working in a lab; it’s a lot more interesting to me. And also just working in the water with native plants is very interesting,” said Newson.

“I was really interested in getting into more of the shoreline science and also learning which native species were planted there,” said Girgenti. “I really love working here. I’ve never really been involved this much in science, so this has been a really great experience—just all of the problem solving that we’ve had to do over the course of the summer.”

Newson also enjoyed the communication aspect of her work, as Garden visitors stopped to ask what work she and Girgenti were doing along the shoreline. She was especially excited to share with them and her fellow REU interns that “the purpose of why we are doing this is that it provides a beautiful site for visitors to see, it helps with erosion, and also improves aquatic habitat.”

Although the interns have left the Garden for now, the data they collected will have a lasting impact here and potentially elsewhere. Kirschner is currently working with his colleagues on the data analysis to complete a comprehensive set of recommendations for future use.

©2016 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org