The plants you see from your train seat on the Metra Union Pacific North line may help conservation scientists learn about how urban areas impact native bees.

Although most people think of honeybees when they think about bees, there are more than 4,000 native bee species in the United States and 500 species in Illinois alone. Like their honeybee counterparts, native bees are undergoing global declines, making them an important conservation concern. With the growth of urban areas, native bees may be faced with new challenges, yet we don’t know the extent that urban areas impact native bees.

My research at the Chicago Botanic Garden is investigating how urban areas may affect native bees in Chicago. Chicago is an ideal city to study the impact of urbanization on native bees because the intensity of urbanization slowly wanes from the urban core of the city out into the surrounding suburbs.

To explore native bee communities along this urbanization gradient, I have a series of eight sites along Chicago’s Union Pacific North Metra (UP-N) railway. I chose the sites along the rail line because they followed a perfect gradient from very urban to very suburban. I was also drawn to them because most of the vegetation around the sites is unmanaged and composed of similar species.

All of the sites vary in the levels of green space and impervious surface (concrete/buildings) surrounding the sites. Sites near downtown are surrounded by nearly 70 percent impervious surface, while sites near the Chicago Botanic Garden are surrounded by just 15 percent impervious surface.

[Click here to view video on YouTube.]

Studying bees in this area along the Metra line allows us to ask a variety of questions about native bees. For instance: Are there fewer bees in highly urban areas? Are there different bees in natural areas compared to urban areas? Do the bees in highly urban areas have different traits than those in natural areas?

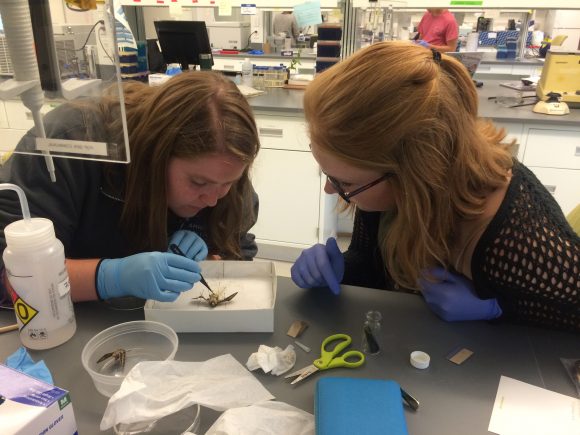

This summer, a few interns at the Garden and I have been gathering and sampling bees at each of my eight field sites. To catch the bees, we use two methods. First, we set out fluorescent colored bowls with soapy water that attract and capture the bees. Secondly, we use a butterfly net to capture bees at the site throughout the day. When we are finished sampling, the bees are taken back to the lab at the Garden’s Daniel F. and Ada L. Rice Plant Conservation Science Center and pinned for future study.

In addition to collecting the bees, we also record all of the flowering plants and count how many flowers are blooming at the sites.

Although our days are currently filled with fieldwork and pinning, in the fall we will spend almost all of our time in the lab identifying the bees down to the genus or species level. When we have all of the bees identified, we can then start analyzing the data for my master’s thesis and answer some of the questions we have put forth. We suspect we will see a higher abundance and diversity of bees in sites located in more natural areas with more flowering plants.

My research will help us understand how urban areas are shaping native bee communities and help us determine what landscape features promote native bee diversity in urban environments, some of which can be implemented in urban restoration projects. We also hope that this work will illuminate the amazing diversity of native bees we have here in Chicago.

©2018 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org