The 2017 Pantone color of the year has us doing somersaults at the Chicago Botanic Garden. Pantone’s “greenery” has inspired us to discuss the importance of green space and nature’s role in our well-being.

Every year, Pantone selects a color of the year. This year’s color selection, “greenery”—a revitalizing shade “symbolic of new beginnings”—inspired us to discuss the benefits of spending time in nature with our Horticultural Therapy participants—a conversation worth sharing with the entire Garden community.

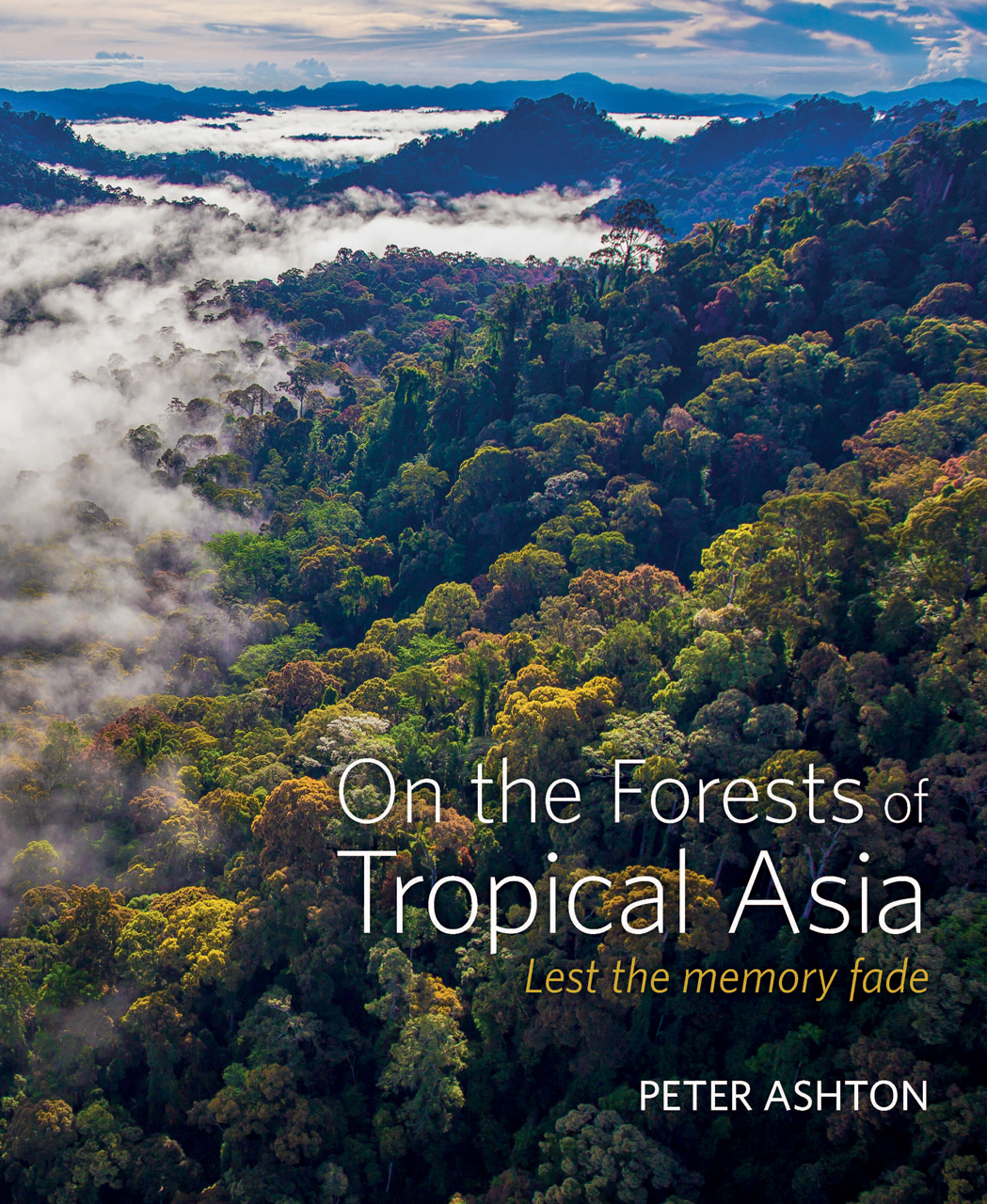

The color “greenery” brings many images to mind: lush forests, fruits and vegetables, fields of grass, and wild jungles. Being in spaces of green, or viewing them from inside, brings about psychological and physiological changes in our bodies. It slows our breathing, reduces stress, and encourages us to take in what is around us.

Why does “greenery” impact us the way it does? There are countless reasons why we feel calm, restored, and connected while in nature. Largely, it is because we are connected to it as human beings. The Biophilia theory, formulated by evolutionary biologist E.O. Wilson, teaches us that because our survival has been linked with nature (water, shelter, food), our love of it is built into our DNA.

Being in green space allows us to rest our minds. More specifically, it allows our directed attention a chance to restore. Directed attention is what we use to concentrate on the day-to-day tasks—sending emails, conducting meetings, taking exams, etc. Our directed attention can quickly become fatigued when it is overworked. This is where nature comes to the rescue.

According to researchers Rachel and Steven Kaplan, nature provides us with elements of “soft fascination,” such as watching tall grasses in the wind or listening to a babbling brook. These elements engage our involuntary attention—attention that is reactive to stimuli and doesn’t take cognitive effort—and when our involuntary attention is engaged, our directed attention gets to take a break. Creating opportunities to take breaks in green space has been statistically proven to increase concentration and alertness, happiness, and connectivity—no matter one’s age, ability, or background. As we like to say, nature (or “greenery”) is one of the best vitamins you can take to keep up with the hustle and bustle of life.

Theories and studies, such as the ones listed above, have inspired a resurgence in restorative landscapes. This resurgence has led to outcomes such as the following: greater number of gardens in healthcare facilities; nature-based curriculums and education centers (e.g., the Nature Preschool at the Garden); and professional development opportunities such as the Healthcare and Therapeutic Design Professional Practice Network in the American Society of Landscape Architects, and the Chicago Botanic Garden’s Healthcare Garden Design Certificate Program.

There are many elements one could incorporate when creating a therapeutic green space. When we design a garden with therapeutic intentions, we include some of the following features:

- A 7:3 vegetation vs. hardscape ratio (70 percent vegetation; 30 percent hardscape)

- Opportunities to engage with nature, such as raised beds/vertical plantings with high sensory plant material

- Elements of soft fascination (e.g., water features, tall grasses, bird feeders, butterfly gardens)

- Accessible and comfortable garden elements (e.g., smooth surfaces, ample shade, and seating areas)

Most importantly, we design spaces that create a positive distraction to the everyday experience. It is important that spaces of “greenery” evoke joy and excitement, engaging visitors in the space with or without planned activities.

Visiting a green space, even viewing one from inside your home or office, brings about positive and impactful changes in our bodies and minds. It is one of the most universally accessible and free healthcare resources in our modern world. At the Chicago Botanic Garden, we cultivate the power of plants to sustain and enrich life. We believe strongly in the power of “greenery” and its impact on our health and well-being. Through thoughtful display gardens, designs, programs, and research, we continue to educate the public and inspire future generations to become stewards of the environment. After all, a little “greenery” goes a long way.

Interested in learning more about the importance of green space for health and well-being? Read about the upcoming seminar, Gardens That Heal: A Prescription for Wellness on May 10, 2017.

©2017 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org

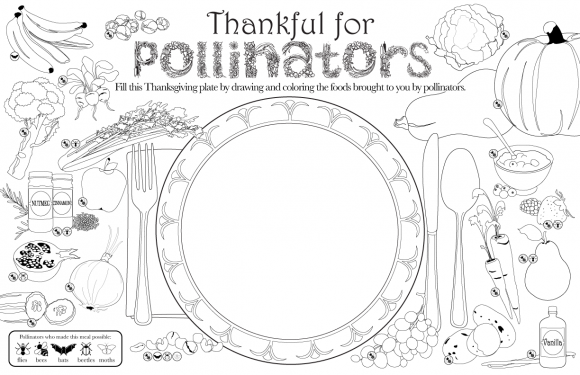

Instructions: Click on the image above to download our placemat to enjoy with your feast.

Instructions: Click on the image above to download our placemat to enjoy with your feast.