Last month, torrential rains fell over much of our region, particularly in Lake and McHenry counties, as well as southeastern Wisconsin. Here at the Chicago Botanic Garden, high water levels in the Skokie River forced us to close on July 13 and 14—the first time in the Garden’s history that we’ve been closed to visitors for two consecutive days.

So what exactly happened that required us to close? And how did the flooding affect our plants?

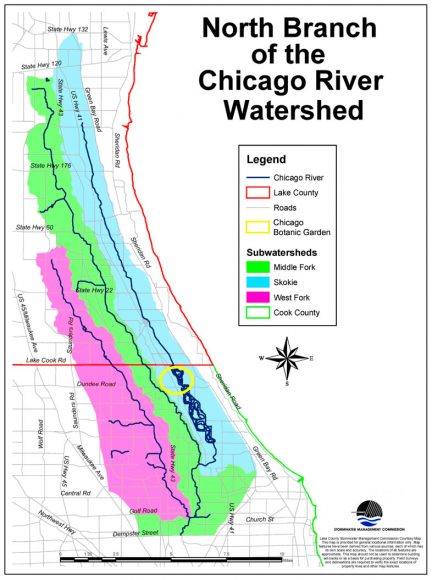

The Garden is situated in the “watershed” of the Skokie River that extends north to Waukegan. A portion of the rain that falls in this upstream, 20-square-mile watershed eventually finds its way to the Skokie River. During the early morning of July 12, between 3 and 5 inches of rain fell in that watershed area over a matter of hours, resulting in a rapid rise in the Skokie River as it flows around the west side of the Garden. In fact, the rainfall was so severe that portions of the village of Lake Bluff (located in our watershed) experienced rainfall intensity and quantity that is predicted to occur with a frequency of only about once every 140 years.

Prior to the Garden’s creation, the Skokie River meandered through the middle of our property. As the Garden began to take shape in the late 1960s, heavy construction equipment excavated our lakes (some exceed 16 feet deep), and those soils were then used to create the islands and display gardens that you enjoy today.

At the same time, the Skokie River was moved into a defined channel on the west side of our property near the highway, and two dams were installed at the north and south ends of our lake system to isolate it from the river except during high flows (see graphic). These dams were installed to help protect communities downstream of the Garden from flooding: if levels in the Skokie River rise high enough, river water flows over the north dam into the Garden lakes and we’ll temporarily store over 100 million gallons of floodwater. After the river’s flood peak has passed, we slowly release that water out of the Garden’s lakes and back into the Skokie River.

Last month’s flooding at the Garden was dramatic. Our lake levels rose more than 5.5 feet above normal and were on par with the highest we’ve ever encountered. At one point early in the flood, an intersection along the Garden’s visitor entrance was submerged under more than 30 inches of water—thereby necessitating our closure.

The image below shows one of our service roads during normal water levels as it crosses a narrow point in our lake system. Compare that image to the video, taken at the peak of the floodwater inflow to the Garden, showing swift and powerful water flowing through this area.

About three days after the heavy rains fell, the flood peak had passed, and the Garden was able to begin releasing lake water back into the Skokie River via a 10,000 gallon-per-minute pump near the south dam. Nine days later, all 100 million gallons of floodwater had been removed and our lake levels were back to normal.

The images below illustrate the extent of the high water levels at the Garden. Remember, at their peak, the lake levels were more than 5.5 feet above normal.

Because the Garden was intentionally designed from the very beginning to accept and temporarily store floodwater from the Skokie River, we’ve experienced few long-term impacts from the recent flood. None of our buildings took on any water. Most of the vegetation near the lakeshore that went underwater survived. There was some damage to plants in the Garden—a few inundation-sensitive shrubs and herbaceous plants, as well as some turf were affected (particularly along the water’s edge of the Malott Japanese Garden). Some were pruned and others may need to be replaced with more water-tolerant taxa. Importantly, more than 500,000 native shoreline plants that we’ve installed along the Garden’s lakeshore withstood being underwater for up to nine days without impact. These plants will continue their important “engineering function” to stabilize our fragile shoreline soils and keep the slopes from eroding into the lake.

The recent heavy rainfall and flooding were of historic proportions and caused devastation to many communities in our region. Looking forward, residents can take steps to help lessen flooding: for example, installing a rain garden on your property can help reduce flooding, particularly for small- and modest-sized storm events; click here for more information. Regional solutions for stormwater management can be particularly beneficial for larger rainfall events. Countywide stormwater management agencies in our region work to implement flood control programs and help homeowners who have been affected by flooding. For more information about these agencies and the programs they offer, in Cook County, contact the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District; in Lake County, contact the Lake County Stormwater Management Commission.

And so while the recent flooding may have left a bit of soil residue on some leaves of plants located nearest the lakeshore, rest assured that all is quite well here at the Garden. In fact, the frequent rains this summer have contributed to luxuriant growth and some amazing blooms, and we look forward to a continued explosion of color as summer progresses into fall.

©2017 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org