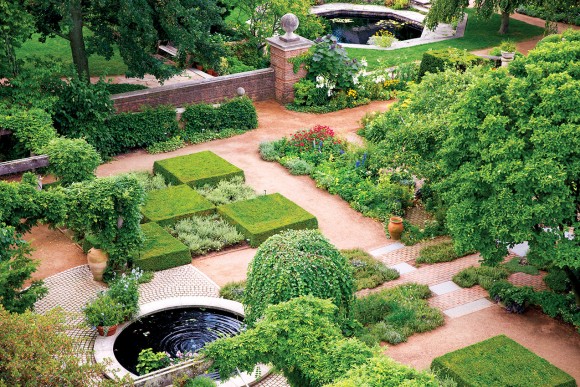

Step past the sleepy stone lion, breathe in the cowslip primrose, and listen to the water trickle into an eighteenth-century lead cistern—the feeling is as timeless as the tiny thyme plants growing between the hand-pressed bricks. So how do we preserve that timeless feeling while making sure the English Walled Garden withstands the rigors of time?

Dedicated in 1991 by Princess Margaret, the younger sister of Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II, the English Walled Garden features six garden rooms, surrounded by boundaries made of stone, brick, hedges, and trees. (At the dedication, Princess Margaret, by the way, wore a heavy, royal blue coat, buttoned to the collar; in a one-minute speech, she thanked the Garden for ensuring the authenticity of the English Walled Garden, according to a Chicago Tribune story. But we digress.)

Like all gardens, this one is subject to constant change. Some plants overgrow their space and need pruning. Trees cast shadows over sun-loving perennials. And some plants succumb to disease or insects. Through generous funding from the Woman’s Board of the Chicago Horticultural Society, the English Walled Garden is updated periodically. Renovations are made in consultation with the garden’s designer, renowned landscape architect John Brookes, Member of the British Empire (MBE).

Brookes most recently toured the garden in 2012 with Chicago Botanic Garden staff members, including Tim Johnson, director of horticulture, and Heather Sherwood, senior horticulturist. This year, as part of a new restoration project, the staff is rethinking the plantings. Some plants will be replaced with varieties that have more desirable qualities, such as disease resistance, increased vigor, a longer bloom period, or lower maintenance. “We’re going back to the original design plan and where it called for blue iris, we’ll work to find varieties that are new to the Garden’s collection and that fit the parameters of the original design,” Sherwood said.

“We’re also simplifying the diversity of the plantings at John’s suggestion,” Johnson added. “It’s a complicated, multilayered process that will be done in phases.” One high-priority project will be to overhaul the perennial borders so visitors can continue to experience the garden throughout the year.

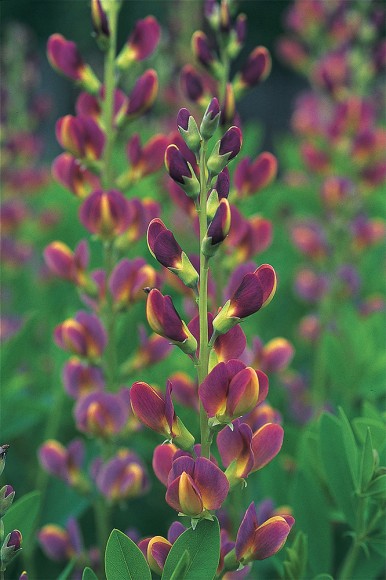

In designing the garden, Brookes said his intent was to present a typical period English country garden that would evoke as many of the senses as possible. The garden “should be visual, of course, with color, but also scent and texture in the planting, and a feeling of it all not being too immaculate,” Brookes said. “Plantings should be full and almost overflowing their borders. It should be a joyous and restful place above all else.”

This post was adapted from an article by Nina Koziol that appeared in the summer 2014 edition of Keep Growing, the member magazine of the Chicago Botanic Garden. At that time, the Woman’s Board of the Chicago Horticultural Society was in its third year of “Growing the Future,” a $1 million pledge to the Chicago Botanic Garden. Proceeds from that year supported renovation of the English Walled Garden and replacement of trees damaged by the emerald ash borer.

©2014 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org