At Butterflies & Blooms on Monday, I saw something I had never seen before in my five years as a butterfly wrangler at the Chicago Botanic Garden. I noticed that a leopard lacewing’s right wings were bright orange, just like any other male of the species, but the left wings were beige—only females have beige wings. This lacewing was half male and half female, or a gynandromorphic butterfly.

That morning, when I had discovered the male-female lacewing, butterfly visitors had been waiting for me to release butterflies from the pupae chamber. So I packed up the lacewing, with all of the other newborns. I then released each of the two dozen butterflies that had hatched that morning, saving our special discovery for last. I got everyone’s attention and announced, “This is extremely rare! As a butterfly wrangler, I have released many thousands of butterflies, but this is the one and only butterfly that is literally half male and half female!” The visitors were fascinated by the lacewing, which sat on the tip of my finger. Then it took flight and was free in the blink of an eye. Luckily, one of our volunteers snapped some beautiful photos.

Later, it occurred to me that this specimen could actually be a valuable contribution to science, and if nothing else, something that everyone should get a chance to see. I tried to find and capture it so an expert could take a closer look. A full day went by without anyone seeing it. I was afraid we had missed an opportunity to contribute something special to the scientific community, but our luck was about to change.

On Wednesday morning, I was chatting with a young butterfly enthusiast about the gynandromorphic lacewing. I asked him if he could keep an eye out and possibly help me find it. He said, “Oh, you mean like this one?” He turned and pointed to the rare creature, which was sunbathing just behind his head. I couldn’t believe it. I offered to name the butterfly after him, but he modestly declined. I’m still trying to reach out to experts. Meanwhile, after that, I brought the special butterfly back into the pupae chamber, where it has been on display to visitors. I have been feeding it by hand, using a piece of foam dipped in fruit juice and Gatorade, which the butterfly seems to love.

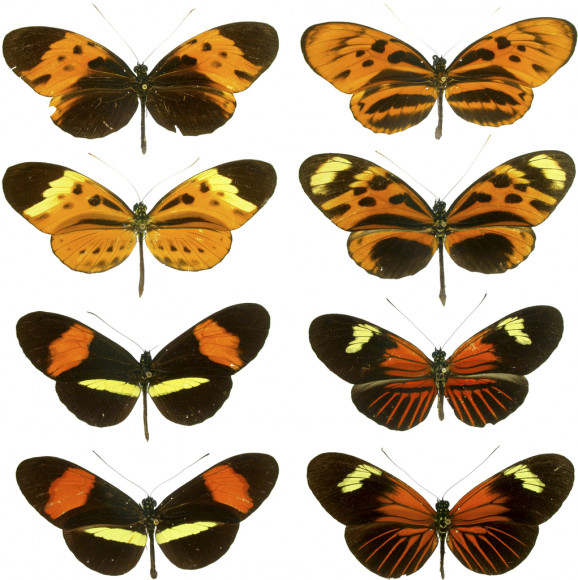

Here is a little information about gynandromorphism. Gynandromorphs are very rare, but can be found in birds, fish, crustaceans, and butterflies, among other organisms. Usually, gynandromorphs have an uneven mixture of male and female features, but our special butterfly has an even rarer form of gynandromorphism because the male and female traits are bilateral, meaning they are split perfectly down the center of the body. How rare are we talking? In a 1980s study, only five out of 30,000 butterflies displayed gynandromorphism.

So how does gynandromorphism occur? There are several possibilities having to do with mishaps that occur during early cell division. Butterflies have a W and a Z chromosome for female and male, respectively. Sometimes, the W and Z chromosomes get stuck together during cell division, resulting in a mixture of male and female traits. In another scenario, the embryo is “double fertilized,” resulting in both female and male nuclei throughout the organism. The causes include bacterial or viral infections, ultraviolet radiation, and other environmental factors that can alter an organism’s DNA during division and growth.

In any case, it’s cool to have a butterfly with such a rare deformation that is still fully able to exist as a healthy adult, sipping nectar and basking in the adoration and fascination of its fans. We have not yet named this butterfly, so please leave some suggestions. The typical lifespan of an adult butterfly is about two weeks, so drop by Butterflies & Blooms and say hello to our newest celebrity.

©2018 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org