This is the story of a road trip I took with some corpse flowers, the rock stars of the plant world. One of the hallmarks of the Chicago Botanic Garden’s plant collection is the more than 70 species of Amorphophallus. In particular, Amorphophallus titanum, also called the titan arum or corpse flower, has gained attention because of its very large flower and pungent fragrance at bloom time—a hybrid of week-old gym socks and a rotting mouse that you just can’t seem to find in your kitchen.

The Garden began collecting titan arums, or corpse flowers, in 2003. There’s a worldwide conservation effort to preserve the species, as it is considered “vulnerable”—unless the circumstances threatening its survival and reproduction improve, the species is likely to become endangered.

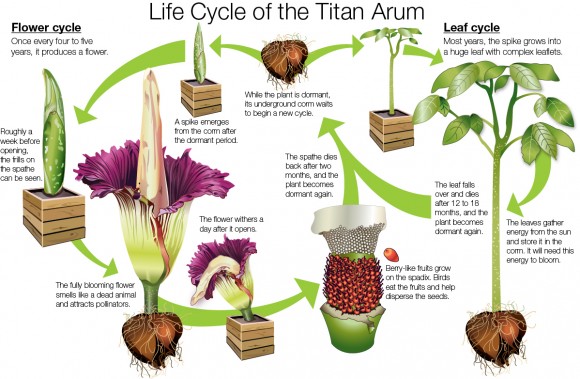

Our titan arums began blooming about three years ago. The first one, Spike, failed to bloom, but shortly after, in September 2015, Alice the Amorphophallus bloomed in all of its stinky glory. At one point, we had two, Java and Sumatra, in their bloom cycle at the same time.

Over time, our family of titans has grown. Many of the Garden’s corpse flowers share the same lineage, and the Garden decided to share some of our titan wealth with other botanical institutions. It is important to build genetic diversity in our collection and at other botanical institutions and to understand more about these plants through genetic assessment work being conducted by Garden scientists.

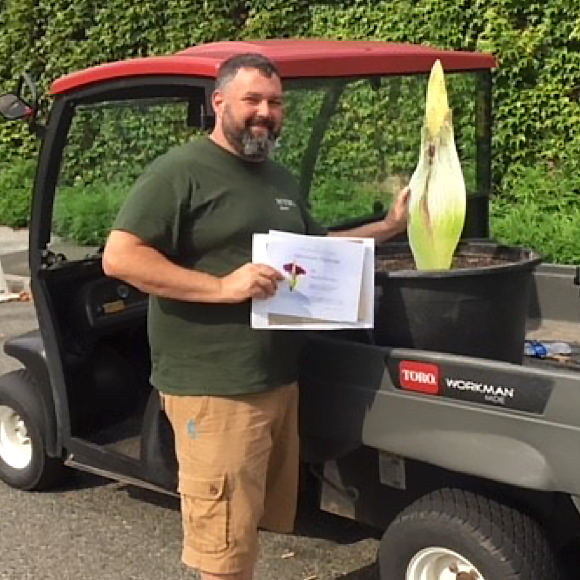

I volunteered to captain the Titan Express, which would deliver the titan arums to their new homes: “Pat” to the New York Botanical Garden, “Sprout,” which bloomed in April 2016 at the Garden, to Longwood Gardens in Pennsylvania, and “Kris” to Chanticleer Garden in Pennsylvania.

We departed the Garden on August 17. All aboard the Titan Express!

My plan was to make it to the New York Botanical Garden by 2 p.m. the next day. Of course, I had several hundreds of miles and the George Washington Bridge to deal with. Even though I left Ohio at 4 a.m., I arrived at NYBG two hours late. Marc Hachadourian, director of the Nolen Greenhouses and curator of the Orchid Collection, graciously met me on a Saturday and more graciously waited two additional hours for my arrival.

With Pat safe and sound, I headed to the New Jersey Turnpike. As much as Philadelphia and Pennsylvania are identified by the Phillies, Eagles, cheesesteaks, and the Liberty Bell, the iconic Wawa convenience store dots the landscape and its coffee rivals Starbucks.

Since I was back in my old “stomping grounds,” I tried to add in visits to see friends, family, and colleagues, as well as take care of some additional botanical business. I conducted a national collections review for the University of Delaware Botanic Gardens in Newark, Delaware.

Feeling weak after a long day of critical thinking about Styrax and Baptisia (two collections under consideration for a national status), I retreated to the regionally famous University of Delaware Creamery for some toffee-flavored sustenance.

Titan No. 2, Sprout, was destined just north of the Delaware border to the Longwood Gardens.

After Longwood, I headed to the beautiful Chanticleer Garden in Wayne, Pennsylvania. Intern Jack McCoy and grounds manager Jeff Lynch stand among some younger titans they received from the Chicago Botanic Garden a couple years ago.

While in the area, I had a chance to visit Doe Run, which was the famed garden of plantsman, Sir John Thouron, and which is now owned by the owner of Urban Outfitters, Richard Hayne. The estate sits in beautiful Chester County, which is rolling countryside with many equestrian-related activities. While Philadelphia and Wilmington, Delaware, create a significant megalopolis, there remains a reasonable amount of farmland and a very pastoral countryside.

Wrapping up the few days on the Titan Express on the East Coast, I had to stop by the Scott Arboretum of Swarthmore College, where I worked for 27 years. And while in Swarthmore, I headed to my house, Belvidere, which I still own, but is rented to a horticulturist at the Scott Arboretum, Josh Coceano.

After several long days of titan tribulations and adventures, a stop at a Delaware drinking hole was in the cards.

I made one last stop to see my mom in Haddon Heights, New Jersey. She is an avid gardener and could appreciate my stories of Andrew’s Excellent Amorphophallus Adventure.

More than 1,000 miles later, the Titan Express made its last stop.

©2018 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org