There’s no doubt: it’s a snow drought, and records are falling like…well, like snowflakes should be falling.

- Wednesday we broke the record number of days without a 1-inch snowfall (319).

- Last weekend we broke the 1940 record of 313 straight days with less than 1 inch of snow on the ground.

- Just 1.3 inches of snow (more near the lake) has fallen to date, compared to the norm of 11 inches.

It made us wonder: what does a snow drought mean for your garden?

To find out, we talked with Boyce Tankersley, our director of living plant documentation.

What Snow Drought Can Do to Your Garden

It’s easy to give snow drought the brush-off (no shoveling! no scraping! no wet feet!), but it can damage your plants and affect the soil in your garden. The following can happen in a drought:

1. Moisture loss accelerates. “It’s the combination of no snow cover plus cold winter wind that does the damage,” Tankersley explains. “When there’s no snow, plants act like a wick in the soil, so the wind not only dries out the trees and shrubs, but also the soil they’re planted in.”

2. Soil compacts. In a normal year in the Chicago area, it rains in November, so the moist ground freezes as temperatures drop. Ice crystals form in the soil. As winter progresses, snow piles up, preventing wind from reaching the frozen moisture in the ground. With spring thaws, ground ice melts, creating air pockets and naturally looser soil. In short, Tankersley says, “winter is good for gardens.” Without that rain/freeze/thaw cycle, air spaces can’t form in the soil, so it collapses and compacts, requiring mechanical tilling to loosen it up again.

3. Plants get stressed beyond capacity. In 2012, plants endured an early spring with a late frost, followed by summer and fall drought, and now, snow drought. There’s a real risk of winterkill—the term used when plants succumb to winter conditions. “Check trees and shrubs for buds in early May,” Tankersley suggests, “especially nonnatives like Magnolia soulangeana, which is particularly susceptible to winterkill.” Even well-established, old trees can succumb—forever changing yards and neighborhoods.

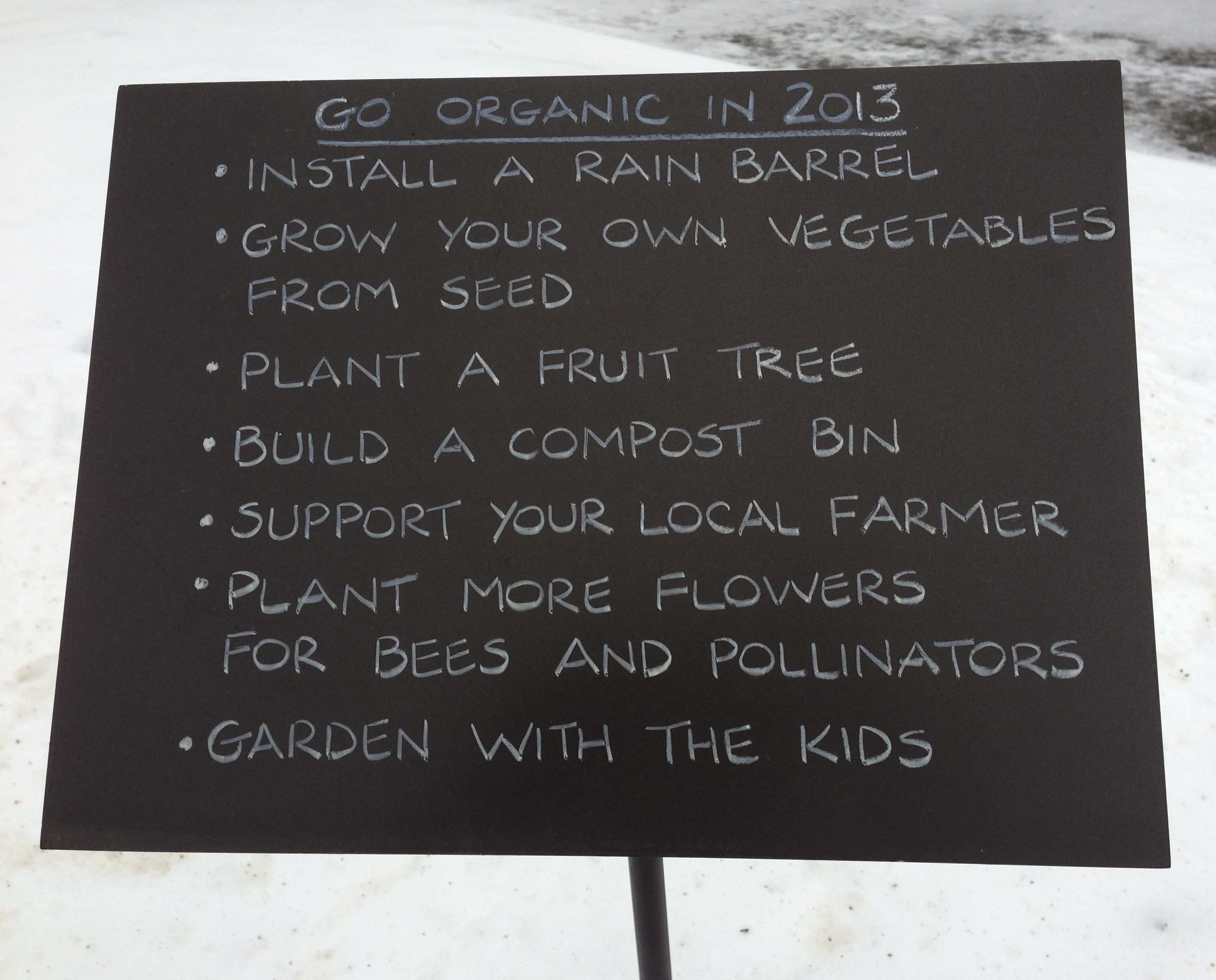

What You Can Do to Help Your Garden

On mild days when temperatures are above freezing, Tankersley’s strategies for home gardeners include the following:

1. Mulch. Like a thick blanket, mulch holds in moisture and creates a layer of insulation for soil. Tankersley’s choice in his own yard? Oak leaf mulch. Why? “The leaves decay slowly, so they release nutrients into the soil over time.” Other options: chopped up plant material from your yard (non-diseased, please), or scattered straw.

2. Add native plants in spring. Natives are already naturally adapted to outside-of-the-bell-curve extremes, with some sporting roots 15 to 20 feet deep. Compare that to a typical landscape plant with roots just 6 inches deep.

©2013 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org