While we are in the midst of the exquisite Orchid Show, the Garden is already planning a summer of Brazil in the Garden, highlighting the influence of Brazil on gardens, arts and culture, and conservation. This seems like a great opportunity to publicize some Brazilian orchids that have been among my favorites all the years I have grown orchids at home.

First, a few facts.

Brazil has one of the highest diversities of orchid species of any country in the world, with more than 2,500 species reported, and no doubt many more undescribed species from the botanically unexplored interior. If you enjoy orchids at all, you have already seen Brazilian orchid species or the hybrids derived from them. Just a few of the well-known orchids that are indigenous to Brazil are many of the Cattleya species as well as many of the former Sophronitis and Laelia species now included in Cattleya; also species from Epidendrum, Maxillaria, Miltonia, Oncidium, Phragmipedium, Stanhopea, and others. The national flower of Brazil—Cattleya purpurata (formerly Laelia purpurata)—is also an orchid.

The native orchids of Brazil are often epiphytes growing on trees and shrubs, but can also be terrestrial, and even lithophytes (growing on rocks). They can be found from hot and humid lowland tropical areas, to seasonally dry and cooler interior regions, to high elevations in cloud forests. The care of Brazilian orchids and their hybrids in cultivation is as varied as the number of species and their habitats, but where they naturally occur provides clues for how to grow them in cultivation. Luckily, the vast orchid literature available often includes information on their culture.

Which brings us to Cattleya coccinea, the compact—yet brilliant—jewel of my orchid collection.

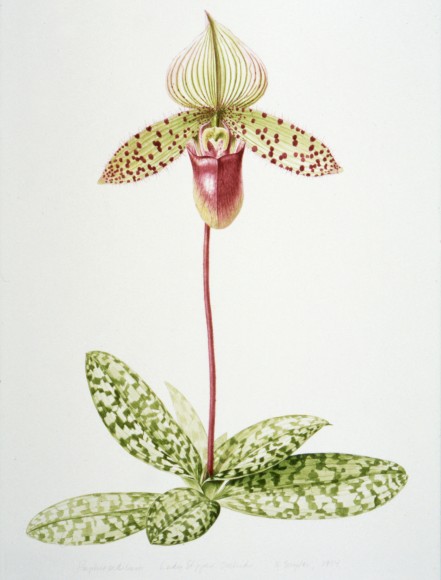

Cattleya coccinea

Formerly recognized and still more commonly referred to as Sophronitis coccinea, C. coccinea is one of perhaps six to nine species and as many varietal color forms included in the former genus Sophronitis. While all the species are delightful in their own right, C. coccinea is the best known. It has long been grown, line-bred (crossed within the species) to improve it, converted to tetraploids (double the typical number of chromosomes) to produce plants with even larger flowers, and especially used in breeding to impart large bold flowers on compact plants. Literally thousands of orchid hybrids have C. coccinea lurking in their background. But I prefer the species or hybrids that are at least 25 to 50 percent C. coccinea, and so still bear a strong resemblance to the species.

Cattleya coccinea is a diminutive grower, with cylindrical pseudobulbs less than 1 inch tall, each topped by a solitary leaf all of 2 to 3 inches in height. A clue you are giving your C. coccinea sufficient light is when each leaf has a red stripe on top of the mid-vein. Under my growing conditions, C. coccinea can produce flowers any time from November to May, and will often bloom two or three times in succession. One to two flowers are produced per new pseudobulb. The flowers can be from 1 to nearly 3 inches wide in the best forms, dwarfing the plant. Flowers are a brilliant red to orange-red with some yellow and/or orange in the small lip. Look for forms with flat flowers and broad overlapping petals. They are always a draw in bloom. Related species are less frequently encountered. Cattleya cernua (Sophronitis cernua) has much smaller flowers but produces more per growth, is very vigorous, and tolerates warmer summer temperatures. There are yellow-flowered versions of both C. coccinea and C. cernua, but these are very hard to find and are priced accordingly. Cattleya wittigiana is similar to C. coccinea but with attractive rosy-pink flowers instead. It has been put to good use in breeding. Confusingly, C. wittigiana is also known as C. rosea, Sophronitis wittigiana, and Sophrontis rosea. The other species are rarely seen.

Tips on cultivating Cattleya coccinea

Culture of Cattleya orchids can be demanding. In its relatively high-elevation native habitats in Brazil, C. coccinea is an epiphyte on trees and shrubs, receiving strong light to full sun, high humidity, strong air movement, and cool temperatures. Try to duplicate these conditions in cultivation. I grow mine mostly in New Zealand sphagnum moss in small clay pots, replacing the moss every winter. They can also be mounted on small pieces of cork bark with a bit of sphagnum moss to help retain moisture. Do not repot them in the summer. Cool temperatures are optimal, with nights as low as 45 degrees Fahrenheit (I aim for around 52-degree nights) and day temperatures no higher than 86 degrees in the summer. Constant high relative humidity and excellent air movement are essential. Never allow the roots to dry out for too many days. These are also sensitive to hard water. If you can, water with rainwater if your water quality is suspect. I fertilize mine weekly when in growth with a variety of fertilizers, alternating 15-5-15 Cal Mag with an occasional 30-10-10 acid feed. (Other growers rarely fertilize at all. It is a matter of personal preference and cultural conditions.)

The former Sophronitis species are not for beginning orchid growers. But with attention to their cultural preferences, they can thrive in the hands of experienced orchid growers. I adore them for their interesting foliage, dwarf habits, and their vibrant and glowing flowers that dwarf the plants. Look for their easier-to-grow hybrids as well.

The Chicago Botanic Garden does not have any of the former Sophronitis species in its collections (I’ll work on that), but there is a good chance that at least some of the species, or hybrids from them, will be on display at the Illinois Orchid Society Spring Show, held March 11 and 12 here at the Garden. The IOS show, which is layered on top of the Garden’s Orchid Show, will include numerous exhibits, judging of the best plants, multiple vendors with plants and growing supplies for sale, an information desk, and a repotting station. Also, look for Brazil in the Garden in our many gardens and events this summer.

Be sure to visit!

©2017 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org

First we learned that one-third of all the ice cream that Americans eat is vanilla.

First we learned that one-third of all the ice cream that Americans eat is vanilla.