There’s less mystery in the natural history of aquatic green algae and its relationship to land plants, thanks to research co-led by Chicago Botanic Garden scientist Norm Wickett, Ph.D., published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and GigaScience.

The study examined how major forms of land plants are related to each other and to aquatic green algae, casting some uncertainty on prior theories while developing tools to make use of advanced DNA sequencing technologies in biodiversity research.

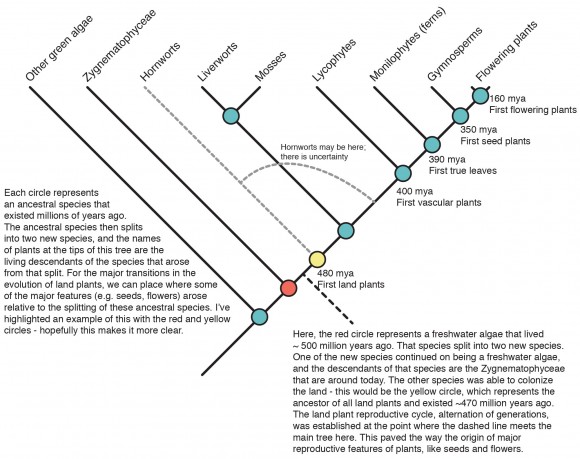

“We have known for quite some time that all plants on land share a common ancestor with green algae, but there has been some debate as to what form of algae is the closest relative, and how some of the major groups of land plants are related to each other,” explained Dr. Wickett, conservation scientist in genomics and bioinformatics.

Over the past four years, he has collaborated with an international team of researchers on the study that gathered an enormous amount of genetic data on 103 plants and developed the computer-based tools needed to process all of that information.

The study is the first piece of the One Thousand Plants (1KP) research partnership initiated by researchers at the University of Alberta and BGI-Shenzhen, with funding provided by many organizations including the iPlant Collaborative at the University of Arizona (through the National Science Foundation), the Texas Advanced Computing Center, Compute-Calcul Canada, and the China National GeneBank. The results released this week were based on an examination of a strategically selected group of the more than 1,000 plants in the initiative.

Researchers dove into the genetic data at a fine level of detail, looking deeply at each plant’s transcriptome (the type of data generated for this study), which represents those pieces of DNA that are responsible for essential biological functions at the cellular level. In all, they selected 852 genes to identify patterns that reflect how species are related.

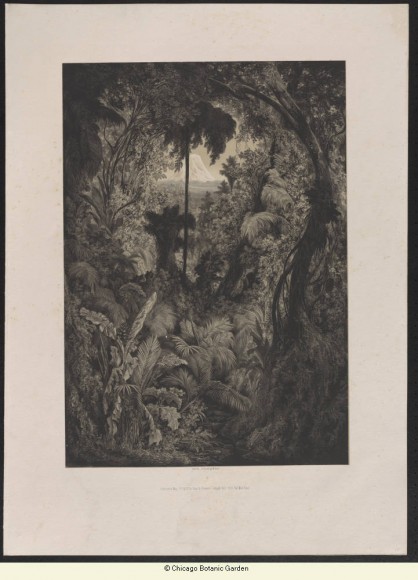

The study is consistent with ideas and motivations that parallel research Wickett is pursuing in work funded by the National Science Foundation program called “Assembling the Tree of Life.” Both studies seek to better understand how the earliest land plants that first appeared more than 460 million years ago evolved from green algae to yield the diversity of plants we know today.

Understanding those lineages, Wickett explained, allows scientists to make better-informed decisions in their research pursuits, and illuminates historical environmental conditions that may have impacted evolution. “Knowing that set of relationships offers a foundation for all evolutionary studies about land plants,” he said.

Using Bioinformatics to Better Understand Our World

Wickett’s expertise in a field of science called bioinformatics allowed him to serve as one of the leaders in the data analysis process, which relied on a set of tools developed by the research team. Using those tools, Wickett helped develop the workflow for a large part of the 1KP study. “The tools we have developed through this project are able to scale up to bigger data sets,” he said. This is significant because “the more data you have, the more power you have to correctly identify those close relatives or relationships.”

By working with a large amount of data, explained Wickett, the team was able to resolve patterns that were previously unsupported. Until recently, the scientific community has largely believed that land plants are more closely related one of two different lineages of algae—the order Charales or the order Coleochaetales, which share complex structures and life cycle characteristics with land plants. However, the study reinforced, with strong statistical support, recent work that has shown that land plants are actually more closely related to a much less complex group of freshwater algae classified as Zygnematophyceae.

A Simpler Ancestor

It may mean that the ancestor of all land plants was an alga with a relatively simple growth form, like the Zygnematophycean algae, according to Wickett. More than 500 million years ago, that ancestral species split into two new species; one became a more complex version that colonized the land, and the other continued on to become the Zygnematophyceae we know today. The unique direction of both species was likely influenced by environmental conditions at the time, and this study may suggest that evolution could have reduced complexity in the ancient group that formed what we now recognize as Zygnematophyceae.

“Our new paper suggests that the order of events of early land plant evolution may have been different than what we thought previously,” said Wickett. “That order of events informs how scientists interpret when and how certain characteristics or processes, like desiccation tolerance, came to be; our results may lead to subtle differences in how scientists group mosses, liverworts, and hornworts, the lineage of plants (bryophytes) that descended from the earliest land plants.”

Wickett can’t help but feel encouraged by the wave of enthusiasm around the release of the publication. “When you get involved in these kinds of projects, it never seems as big as it is—you just get used to the scale. It’s been really great to get the public reaction and to see that people are really excited about it,” he said.

Where We Go from Here

Wickett will convene with the research team in January in San Diego to discuss next steps for 1KP, which will lead to the analysis of some 1,300 species. The team will likely break into subgroups to focus on sets of plants that share characteristics such as whether they produce flowers or cones, or have a high level of drought tolerance.

With the publication of this research, a door to the past has been cast wide open, offering untold access to natural events spanning some 500 million years. After such significant discovery it’s hard to imagine that there could be more in the wings. But with the volume of data generated by the 1KP project, there are certainly exciting results yet to come.

©2014 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org