Like many children, I was fascinated with Beatrix Potter, the creator of The Tale of Peter Rabbit. I remember wanting to visit Hill Top Farm, Potter’s home, after finding a photo of children reading by the fireplace in a National Geographic my parents had.

Those feelings returned after I saw Beatrix Potter: Beloved Children’s Author and Naturalist, on display through February 7 at the Chicago Botanic Garden’s Lenhardt Library. The exhibition gives wonderful insight into Potter’s early life and career, along with her love of nature and preservation. Here are ten things from the exhibition and beyond that you might not know about the beloved children’s author:

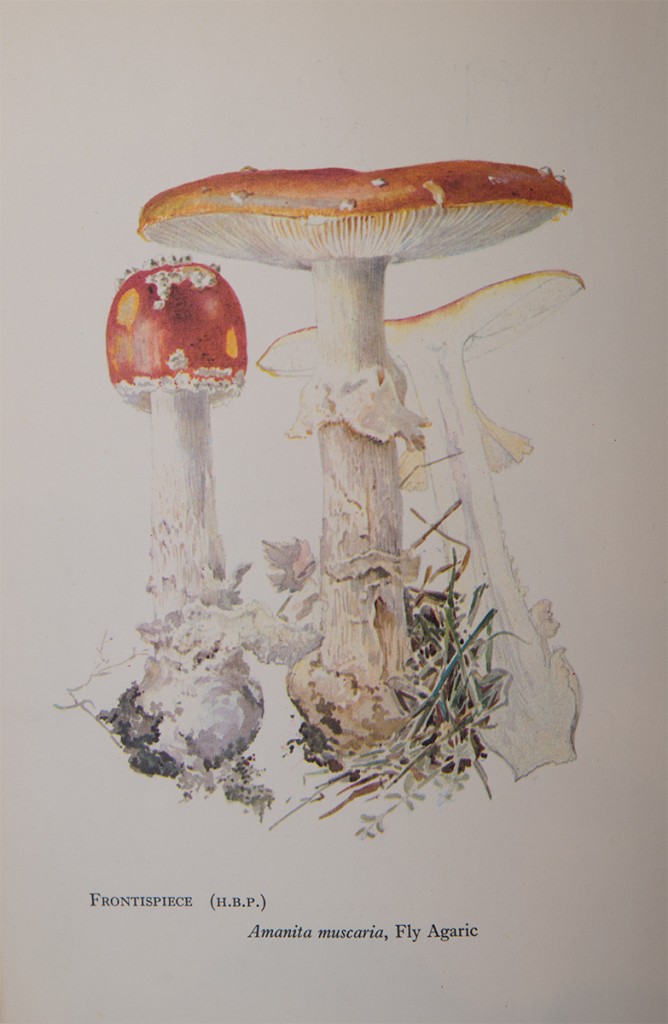

- Beatrix’s full name is Helen Beatrix Potter. She shares her first name with her mother, Helen Leech Potter, who was also interested in drawing and painting—common pastimes for upper-middle-class Victorian women. Beatrix used a paint box inscribed with her mother’s name, and she signed some of her drawings H.B.P.

- It was summer forays from the Potters’ London family home—first to Dalguise House in Perthshire, Scotland, and later England’s Lake District—that inspired Beatrix’s love of nature. Charles McIntosh, the postman Beatrix befriended in the Lake District, would collect mushroom specimens for her to draw. Some examples of her remarkable mycological illustrations are featured in the Lenhardt Library exhibition.

- She kept a secret journal between the ages of 15 and 30, and it was written in code. Though the journal was discovered in 1952, the code was not broken until 1958 by collector Leslie Linder, who then began a massive project to decipher the entire journal. The journal was published in 1966 and gives insights into her thoughts and daily life.

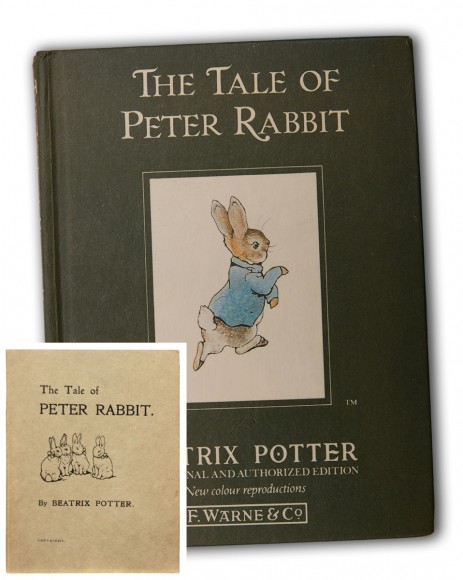

- Her most famous work, The Tale of Peter Rabbit, was first self-published with black-and-white illustrations on December 16, 1901. Peter Rabbit started as a letter to Noel, the ill son of her former governess/companion.

- She purchased Hill Top Farm with proceeds from book sales of The Tale of Peter Rabbit, published by Frederick Warne & Co. (Beatrix had been engaged for a short time to her publisher, Norman Warne, but he died of leukemia before they married.) She learned too late that she had overpaid for the property and was embarrassed about it. Beatrix vowed to be smarter if she purchased additional property and decided she would seek the assistance of a solicitor. As she began to acquire more property, she secured the services of William Heelis. They later married in 1913, when Beatrix was 47 years old.

- She raised sheep. As Beatrix spent more time at Hill Top Farm, she focused her time and energy on raising local heritage livestock—primarily Herdwick sheep—with Kep, her favorite collie. Beatrix dressed in Herdwick tweed skirts and jackets, served as a sheep judge, and was the first female elected president of the Herdwick Sheepbreeders’ Association in 1943. Unfortunately, she died before she could serve.

- The Fairy Caravan, a longer book for older children published in 1929, is autobiographical. Marta McDowell, author of Beatrix Potter’s Gardening Life, wrote of The Fairy Caravan: “A very personal book, she wove in the birds and blooms of memory, writing of old gardens and woodlands of her grandparents’ home in Camfield.” Once I read the exhibition label, I quickly went to my local library and am now reading The Fairy Caravan for the first time.

- She was an ardent preservationist. Beatrix realized that times would change the Lake District she loved so dearly, and she eventually bought 14 farms comprising over 4,000 acres that she donated to the National Trust. Many of her illustrations are directly drawn from the Lake District countryside. If you visit the Lake District, consider ordering Walking With Beatrix Potter: Fifteen Walks in Beatrix Potter Country by Norman and June Buckley.

- Peter Rabbit is extremely popular in Japan. The exhibition shows this through a Japanese catalog of all things Peter Rabbit for purchase. There is even a life-sized recreation of Hill Top Farm you can visit near Tokyo that was built in 2006.

- Her Hill Top Farm still includes many small details of Beatrix’s life. Several years ago when I visited the farm, her clogs were still by the fireplace and, upstairs, the plaster ham Hunca Munca tried to carve in The Tale of Two Bad Mice was in the dollhouse. I almost expected Miss Potter/Mrs. Heelis to pop around the corner.

Beatrix Potter: Beloved Children’s Author and Naturalist closes on February 7, but the Lenhardt Library has a terrific selection of books about and by Beatrix Potter. Check out one of the books to learn more about Beatrix and her many contributions.

©2016 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org