As winter winds disperse prairie seeds and fragrant pinecones tumble down, Bianca Rosenbaum is busy collecting. As much as she would love to forage through the seasonal natural materials outside of her office at the Chicago Botanic Garden, that’s not what she is after these days. Rather, she is gathering data.

Seated at her desk in the Daniel F. and Ada L. Rice Plant Conservation Science Center, Rosenbaum taps away at her computer’s purple keyboard. The Garden’s conservation science information manager is busy finishing her masterpiece—a searchable collection of visual and numeric plant data. The new product is a one-stop-shop for information previously housed in three separate databases and accessible by few.

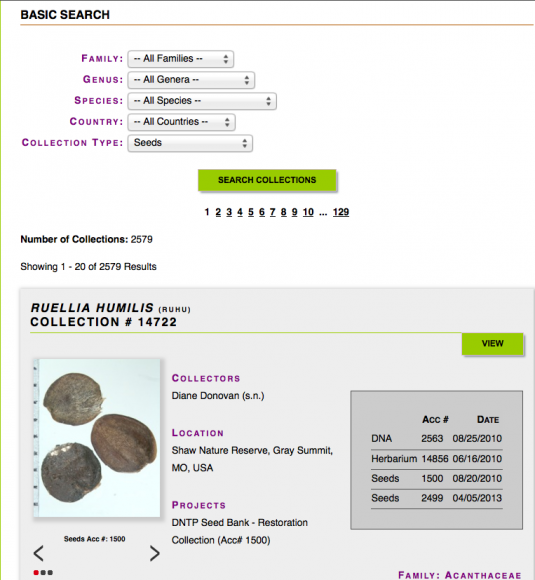

Named the Science Collections database, the project centralizes the Garden’s data on seed collections, herbaria, and plant DNA. For the first time, the information is accessible online by anyone from international scientists to curious children.

“We saw this great opportunity to combine our databases and be able to cross reference collections,” she said. “It’s been very exciting. It’s one of my biggest, most challenging projects. It feels extremely rewarding.”

Since she began working at the Garden in 2002 as an expert in Microsoft Access, Rosenbaum has overseen the safekeeping of the data in all three of these areas as well as other Garden research collections. In just a few years, the way the information was stored and managed became outdated as technology progressed. She was thrilled with the opportunity to advance its management system.

When the Science Collections project began four years ago, one of her first tasks was to identify data used by all three databases and merge them into common tables to eliminate repetition and guarantee standardization. The result was a complicated set of linked tables that comprise the structure for the final product—called a relational database.

She then merged all of the data on each species. Now, rather than going to different databases to find all of the herbarium, seed, and DNA information recorded about a plant, it can be found in one place.

Rosenbaum then worked with the Garden conservation GIS lab manager, Emily Yates, to add a spatial component to the data by mapping plant locations, which are linked to each collection record. Lastly, she built a web page to serve as a portal from the database to the internet.

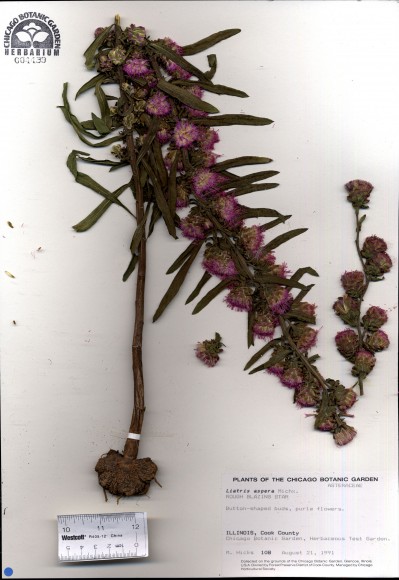

Data from the Garden’s Nancy Poole Rich Herbarium are mainly visual, with 17,000 images of pressed plants alongside notes about location and related details. Information from the Dixon National Tallgrass Prairie Seed Bank includes high-resolution images of seeds from 2,600 species. The program also includes notes about whether the Garden houses material that may be accessed for DNA sampling for a given plant. The records include information on all classifications of regional plants, and some international. Only those labeled as threatened or endangered are not shown on a map.

“This job has totally changed my outlook,” said Rosenbaum, who had no real interest in botany before coming to work at the Garden. “I feel very fortunate that I’ve been here and I’ve been able to combine both the tech world and the environment.”

As a child, she grew her love of technology with encouragement from her parents—an engineer and electronic assembler. She went on to study computer engineering in college, and gained work experience with coding and data management. As a Garden employee, she has coupled those computer skills with a new set of plant-related skills. She is now comfortable with plant names, discussing scientific processes, and even growing her own vegetable garden at home.

Although she spends much of her work day glued to her computer screen, Rosenbaum does find time to look out her window, or step outside to connect with her subject matter. “I think it’s very easy to not notice this world when you are in the tech world, or the business world,” she said. “Now I can connect the two and know what it is I am working on and see what I am working to protect and conserve.”

Rosenbaum often strolls the Waterfall Garden in warm months, but she especially looks forward to spending time in the peaceful Dixon Prairie.

The recently launched database is now open to exploration at www.sciencecollections.org. Check back in coming months for Rosenbaum’s forthcoming addition of advanced search options.

©2014 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org