Plants of Concern volunteers come from many backgrounds, but all share a common denominator: not surprisingly, they are concerned about plants.

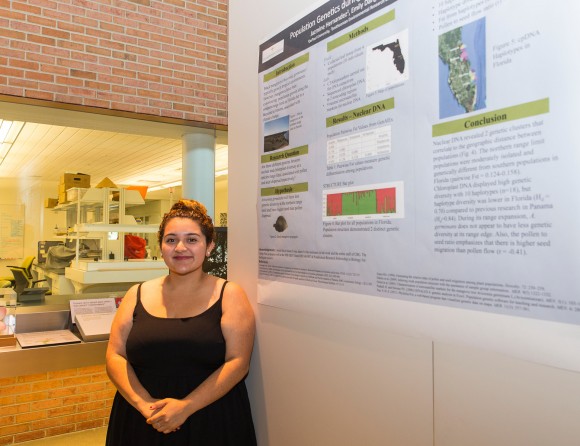

So concerned are these citizen scientists, in fact, that they are willing to traipse all over our region of northeast Illinois and northwest Indiana to monitor hundreds of rare, threatened, and endangered species in a variety of habitats. Their findings help plant scientists understand and work to mitigate the effects of climate change, as well as encroaching urbanization and invasive species.

Here are profiles of three Plants of Concern volunteers, in their own words. We hope these stories inspire you to consider joining their ranks. Another Plants of Concern volunteer recently blogged about her experience as a newbie with relatively little plant-related expertise, and you can find that post here.

Kathy Garness

Bachelor’s degree from DePaul University in visual arts; master’s degree in religious education from Loyola University. Worked for many years as a director of religious education in the Episcopal church, in the commercial art field for more than a decade, and now as administrator and a lead teacher in a nature-based preschool. Earned a botanical art certificate from the Morton Arboretum. Helped develop the Field Museum’s Common Plant Families of the of the Chicago Region field guide.

Bachelor’s degree from DePaul University in visual arts; master’s degree in religious education from Loyola University. Worked for many years as a director of religious education in the Episcopal church, in the commercial art field for more than a decade, and now as administrator and a lead teacher in a nature-based preschool. Earned a botanical art certificate from the Morton Arboretum. Helped develop the Field Museum’s Common Plant Families of the of the Chicago Region field guide.

I started volunteering with Plants of Concern in 2002. I learned about POC after a chance meeting at the REI store in Oakbrook with Audubon representative and Northeastern Illinois University professor Steve Frankel. Steve told me about POC, and that meeting changed my life in a huge way.

I monitor 25 species at nine different sites, including Grainger Woods in Lake County; Theodore Stone in Cook County; several high-quality prairies in Cook, DuPage, and McHenry Counties; and Illinois Beach State Park in Zion. POC assigned them to me because of my interest in and ability to ID many species of native orchids (there are more than 40 just in the Chicago region). But I monitor other plants besides orchids.

Volunteering for POC differs from most other volunteering positions I’ve held [at the Art Institute and the Field Museum] because there is a lot of independence, and also much more technical training. This citizen science is vital to the sites’ ecologists—most agencies don’t have enough funding to pay staff to collect the valuable, detailed information we do. Volunteers also are highly accountable, and you need to be really sure about your species. That knowledge comes over years of participation, but even if someone just participates once, and goes out with a more experienced monitor, the information collected helps fill gaps in our understanding of our natural areas. And it’s way more fun than playing Pokémon, once you get the hang of it!

My advice for prospective volunteers is to go out first with more experienced monitors. Learn from them—they are better than a digital (or even paper) field guide. Clean your boots off carefully beforehand; don’t track any weed seeds into a high-quality remnant. Observe more than just the monitored plants—look for butterflies, listen for birds, notice the dragonflies and frog calls. Tread lightly and watch your step. Bring extra water and a snack. Use bug spray. Learn what poison ivy is but don’t be afraid of it—just don’t get it on your skin! No matter how hot it is, I wear long trousers, long sleeves, a broad-brimmed hat, and thin leather gloves. Never, ever, go out in the woods alone. Let people know where you are going and when you plan to return. Watch the weather signs. Keep your cell phone charged and with you at all times.

Above all, enjoy this one-of-a-kind experience!

Fay Liu

Bachelor’s degree in agriculture technology/animal sciences from Utah State University; master’s degree in food science from the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. Trained as a food-science researcher focusing on meat quality. Researched pork quality for a commercial pig farm/processing plant and a pig genetic company.

I have been volunteering with Plants of Concern since 2012. I am interested in nature and enjoying the outdoors, and this is a fantastic program for me. My family always spent time hiking and fishing on weekends. I grew up in Taipei, Taiwan, where we had easy access to mountains and the ocean—unlike in the Midwest. We also had a container garden on top of our four-story building, and I helped to take care of the plants.

For POC I primarily volunteer at Openlands, which is about 20 minutes from my house. However, I have also volunteered farther away, south to Will County, east to the city of Chicago, and north to Zion.

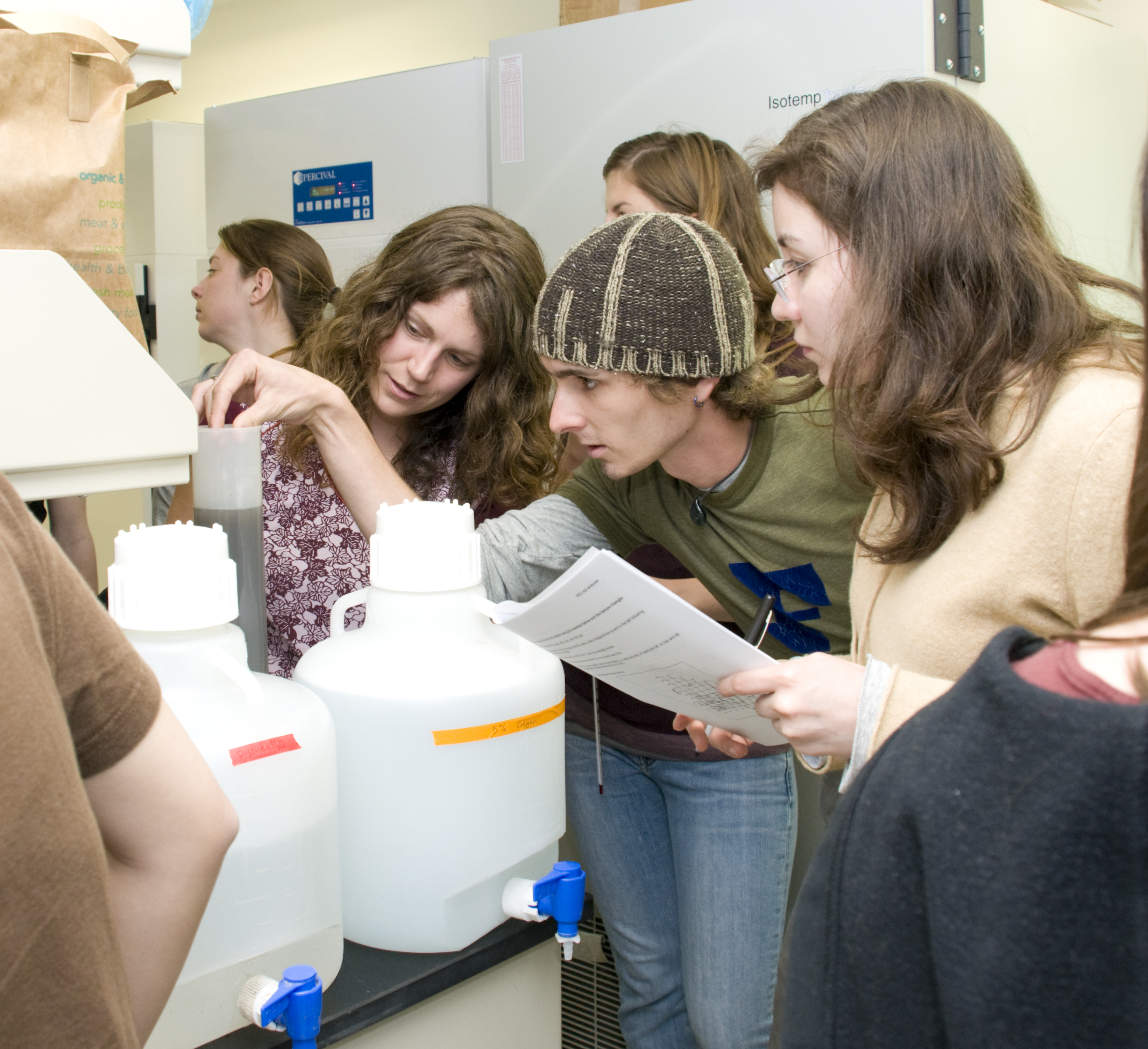

Plants of Concern involves many aspects of science: identifying target plants and knowing the plants surrounding them, locating target populations, and using statistical methods to measure populations. For me, the most fun thing is learning new things each time I come out to the field. Maybe it’s a new plant that I have never seen before, or a new hiking route. The most frustrating times are when it’s hard to find the target plant because the population is low.

The advice I have for prospective volunteers is to keep your curiosity alive!

Karen Lustig

Bachelor’s degree in botany from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign; master’s degree in botany from the University of Minnesota. Has taught botany at Harper College since 1987.

I have been interested in plants since I can remember. My father loved to hike, and my mother was a gardener. Instead of moving furniture around, my mother moved plants. We spent a lot of time outside.

I have volunteered with Plants of Concern since its beginning. I monitored white-fringed prairie orchids with the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and many other plants with the Nature Conservancy even before then. I knew people (still do) at the Chicago Botanic Garden, and I heard about the program from them, so it was sort of a transfer. I remember that when POC started, we worked in forest preserves. I understood why there was a desire to work in protected lands, but I said we needed to include other properties. And the program expanded beyond the preserves!

I actively monitor for POC at Illinois Beach State Park (IBSP) and also help out at Openlands when I have time. The forays are great fun. That’s my favorite thing: getting out there and being with other people and learning about new plants. At IBSP, visitors are expected to stay on the trail. Of course, most plants don’t grow right on it, but you can usually spot them. Once I was looking around for plants and saw this guy sort of thrashing around in the cattails. I reported him since he looked so bizarre out there, and it turns out he was a skipper [butterfly] expert taking samples for the Karner blue butterfly project. I met him later…a really nice guy, it turns out!

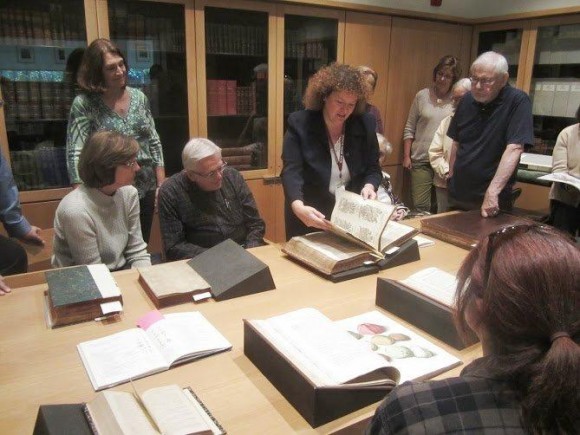

What makes Plants of Concern special is that it is so well run. The staff is quick on feedback and offers lots of help. The training programs are excellent. I’ve heard some terrific speakers, too. Other organizations sometimes don’t seem to have quite the staff or funding for their programs, which can make volunteering challenging. If I had to identify the biggest challenge as a POC volunteer, it would be the paperwork. With POC you can do the entry online, which helps. But filling out forms remains my least favorite thing to do…I just filled out a form [in August] for data collecting I did in May.

My advice to new Plants of Concern volunteers is to go to the workshops—even if you think you know the stuff. It’s amazing what you can learn. And when you first go out, it can be hard just to find the plants, even using a GPS, much less to know what to do when you find them. So go with experienced people!

Students at Harper College have volunteer workdays, and when mine return to the classroom after volunteering with POC groups, they always talk about how knowledgeable and interesting the volunteers are—and these are college environmental science students. It’s great that people can get together and share not just their knowledge but their enthusiasm through Plants of Concern.

Join the ranks of the dedicated people of Plants of Concern: volunteer today.

Plants of Concern is made possible with support from the U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service at Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie, Forest Preserves of Cook County, Openlands, Nature Conservancy Volunteer Stewardship Network, National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, and Chicago Park District.

©2016 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org