Stacy Stoldt is never not working on an exhibition.

Even when the Lenhardt Library’s public services manager is staffing the desk, answering reference questions, and locating articles for staff, the “million and one” details involved in putting together the library’s four annual rare book exhibitions are percolating in her brain.

Stoldt has streamlined the process since she first began working at the Chicago Botanic Garden in 2007, but it remains a lot of work to curate an exhibition. “There’s the research, the writing, the editing, the design, the approvals,” she said last month. “Here we are in January, and we’re in the design phase of our next exhibition, which opens in February, but back in November I was already meeting with someone about books for an exhibition that opens this May. There’s always a deadline looming.”

Stoldt loves her work, and one of her chief pleasures is deciding which literary treasures will be selected. It is a process involving research, more research, and finally, she says, just a bit more research. The excitement of finding the perfect volume has prompted Stoldt to burst into song (just ask cataloger Ann Anderson, a neighbor in the basement office who sometimes joins in).

The public services manager and her colleagues have many volumes from which to choose: in 2002, the Lenhardt Library acquired a magnificent collection of 2,000 rare books and 2,000 historic journals from the Massachusetts Horticultural Society of Boston.

An Exhibition Takes Shape

Before Stoldt begins hunting down books, there are meetings to decide Lenhardt Library exhibition topics for the year. That process begins with a brainstorming session including Stoldt, Lenhardt Library Director Leora Siegel, and Rare Books Curator Ed Valauskas. Sometimes the trio bases their topics on themes within the collection, such as the upcoming succulent show that features the work of A.P. de Candolle and botanical-rock-star-illustrator Pierre-Joseph Redouté.

Alternatively, they might collaborate with another botanical library on a theme, as happened when the Lenhardt Library team worked with the New York Botanical Garden’s LuEsther T. Mertz Library on the recent exhibition Healing Plants: Illustrated Herbals. Other times, they select topics that complement events held at the Garden, such as Butterflies in Print: Lepidoptera Defined, which ran in conjunction with last summer’s Butterflies & Blooms.

Newest Exhibition Focuses on Orchids

The newest Lenhardt Library exhibition complements the Orchid Show and is titled Exotic Orchids: Orchestrated in Print. Running through Sunday, May 11, it features such rare books as Charles Darwin’s seminal On the Various Contrivances by which British and Foreign Orchids are Fertilised by Insects, and on the Good Effects of Intercrossing, published in 1862. Another item is Curtis’s Botanical Magazine, with a beautiful color illustration of Angraecum sesquipedale, also known as Darwin’s orchid. “One doesn’t come alive without the other,” said Stoldt. “I’m always trying to put the connections together for people.”

For some exhibitions, Stoldt does it all—A to Z. For others, she receives the researched text, citations, and selected illustrations from Valauskas or Siegel and develops the material into an exhibition. Once the topics are established, research is completed, and explanatory text is written and edited, graphic designers enter the picture. Stoldt selects images from the featured books to use with the accompanying text, and then the designers work their magic. Along the way, Stoldt and Siegel review the progress. The result is an exhibition compelling not only for its content but for its elegant layout, which extends throughout the display cases that greet visitors as they enter the library.

Accompanying library talks are on Tuesday, February 18, and Sunday, March 9, at 2 p.m.

“For our new Exotic Orchids exhibition, we really wanted to show some bling!” said Stoldt. Within the Rare Book Collection, there was so much to choose from on orchids that she found the selection process daunting. Visitors to the exhibition will find the beauty and science of orchids well-represented, and discover items about orchid conservation and preservation as well.

Art Conservation Key to Documenting Plants

Stoldt noted that conserving the books and the artwork that document a plant’s existence is almost as important as preserving the actual plant. In cases two and three of Exotic Orchids, there are select illustrations from two orchid collections, Les Orchidées (1890) and Les Orchidées et les Plantes de Serre (1900–10), which the Lenhardt Library recently had conserved by the Northeast Document Conservation Center (NEDCC) through grant funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH).

How did the conservation process work? Professionally trained book and paper conservators removed the illustrations from their original acidic bindings; then the inks were tested, the surfaces were cleaned, and the illustrations were digitally photographed. Then the illustrations were placed in chemically stable folders and housed in custom-made boxes made from lignin-free archival boards. Conservation completed!

The Rare Book Collection

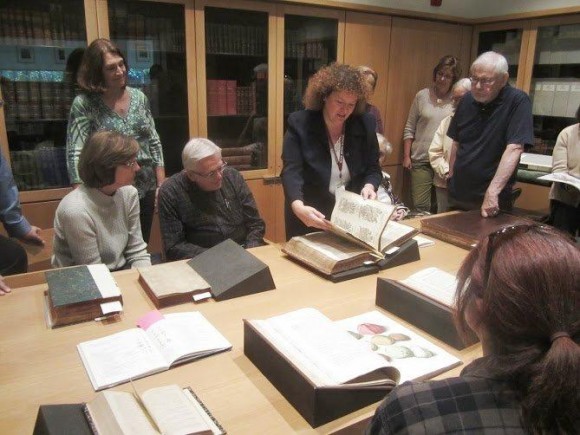

Stoldt recently brought out some rare volumes to demonstrate the variety within the Rare Book Collection. As noted on its web page, the collection reflects a relationship between people and the plant kingdom that has been documented since the earliest days of print, when botanists were not simply plant describers, but explorers.

Out came volume after volume, with Stoldt pointing out noteworthy details about each. Among them was the oldest book in the collection, Historia Plantarum, written by Theophrastus (d. 287 B.C.E.) and published in 1483 (it has some unusual marginalia). There was also an exquisite Japanese book on flower arranging, Nageire Kadensho: Saishokuzu Iri, published in 1684 and donated by longtime library volunteer Adele Klein. Stoldt continued her informal presentation with seemingly boundless enthusiasm, finishing with lush life-size images from The Orchid Album, published between 1882 and 1897.

More than once, Stoldt returned a book to the vault at the end of the show-and-tell only to call, “but wait! There’s more!” as she glimpsed another book she absolutely had to show. This librarian really, really loves her books. And she feels very protective of them.

Stoldt recalled the horror she felt once when she was installing an exhibition, with a rare book exposed nearby on a book “cradle”: “There was a sign that said ‘Exhibit installation in progress: please do not touch the rare books,’ but this person came in from the rain and loomed over it, dripping wet. I got her out of the way, but that was a close one.”

Cultivating Relationships

More often, visitors are sensitive to the delicate state of the Garden’s rare books. Some Garden members make a point of coming to each new exhibition and attending the free gallery talk. “One patron always calls from Wisconsin to find out about the next talk,” said Stoldt. “And once, a library regular who came to a talk told me how much she loved the book Brother Gardeners [about eighteenth-century gardeners who brought American plants to England]. I was able to show her some books by the book’s featured plantsmen, including Joseph Banks, John Bartram, and Phillip Miller, among others. It’s what I call an ‘on-demand rare-book viewing.’ She was thrilled. These are the kinds of things that lead to relationships with people.”

Devoted patrons feel that the library and its exhibitions enhance their lives; in turn, some are moved to enhance the Rare Book Collection. “We have our patrons, and then we have our patron saints,” said Stoldt. One patron who came to the 2009 exhibit on Kew Garden’s 250th anniversary enjoyed the accompanying talk by Ed Valauskas so much that she donated the 1777 edition of Cook’s Voyage, or A Voyage Towards the South Pole, by Captain James Cook, which had been in her family for family for decades. And longtime members John and Mary Helen Slater made it possible for the library to acquire 11 volumes of Warner’s Orchid Album.

Inspiring the Next Generation

Stoldt loves to see the excitement she feels about the Garden’s Rare Book Collection spreading to a new generation. She recalled a day when a grandfather brought his grandson to the library, and the child asked to see a rare book. “I asked him what he was interested in, and he said, ‘poisonous plants.’ First, I showed him Histoire des Plantes Vénéneuses et Suspectes de la France by Bulliard, a book on poisonous plants written in French from the eighteenth century, but what really spoke to him was a book with the ‘coolest illustrations!’ entitled Poisonous Plants, Deadly, Dangerous and Suspect, Engraved on Wood, 1927, by John Nash. This kid was just amazed. I love seeing young readers light up when they’ve found something intriguing for them in print. It’s heart-warming.”

Although that particular drop-in visit and viewing request occurred on a busy weekend day, another library staff member was available to manage the circulation desk while Stoldt showed the books. “I can’t stress enough the importance of making an appointment for a viewing,” she said. “Besides kids, grandparents, and garden clubs, people from all over the world come to Lenhardt Library to see primary resources they can’t find elsewhere. We’ve had writers and scholars from England and the Netherlands, and even a Thai princess, come to see the Rare Book Collection. Everyone is welcome.”

Don’t be surprised if you come to see one specific book in the collection and end up seeing many more. It will be a visit you won’t forget!

Rare book viewings are by appointment only during the hours of 10:30 a.m. until 3 p.m. Monday through Friday, subject to availability. For an appointment, call (847) 835-8201.

Click here to purchase tickets to the Orchid Show online.

©2014 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org