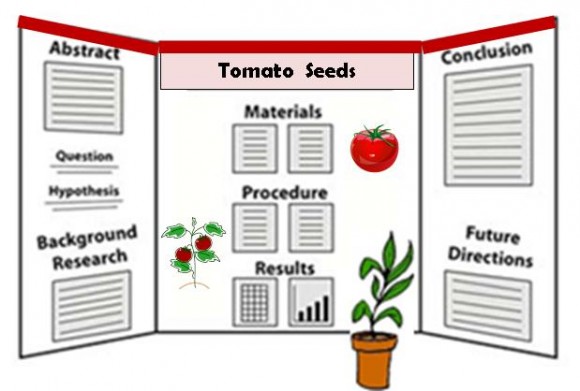

Here’s a science project students can do at home! Try tomato seeds.

As I’ve stated before, we in the education department of the Chicago Botanic Garden are committed to helping parents and teachers find great projects that teach students how plants sustain and enrich life. Last year we talked about using radish seeds; this year, it’s tomato seeds. And like last year, this project can be done by an individual student, a small group or ecology club, or an entire class.

Let’s begin by thinking about tomato seeds. Cut open a tomato and try to pick out a single seed. Go ahead and try it, I’ll wait.

As you will discover (if you didn’t already know) the seeds are coated in a gelatinous substance that makes them slippery and difficult to handle. So the first question is, what purpose does the slimy coating serve?

This is not the kind of blog post where I give you all the answers. That would not be good science teaching. I will tell you that tomato seeds can pass through the digestive tract of an animal and still germinate. Not all seeds can do that. It is possible that in nature, the coating protects the seeds on their journey from the mother plant through the hostile environment of a hungry animal’s gut and on to wherever that animal relieves itself.

Another theory is that the coating prevents premature germination of the seeds while they are inside the warm, moist, ripening fruit. Whatever the true reason—and there may be several—seed savers find it’s better to remove that coating after the seeds are harvested, because they become easier to handle and store.

The natural way to remove the coating is to ferment the seeds in a jar or bowl. It’s a simple procedure.

1. Scoop or squeeze the seedy pulp out of the tomatoes and put it into a bowl. (I prefer glass, but some people use plastic.) Add water equal to the volume of tomato pulp. Cover the bowl with plastic wrap and poke a few holes in the top.

2. Place the bowl in a warm location such as a sunny window. It is going to smell bad, so don’t put it in your dining room, unless you’re trying to reduce your appetite. You will also want to avoid fermenting your seeds next to bananas and other fruit ripening in your kitchen, because it can attract fruit flies. Leave it there for three to five days, depending on the conditions. Natural “beasties” in the air (yeast) will settle on the sugary goodness of the tomato. They will gorge themselves and reproduce, resulting in a yucky mess floating on top of the mixture. This is exactly what you want.

3. After you have grown a nice head of gunk on your seeds, remove that film and throw it away. (Unless you’d like to keep it for some reason.) If you can’t skim all of it, no worries, the remaining goo will rinse off in the next step. Remove any floating seeds, too—they are not viable.

4. Pour the mixture into a sieve or wire strainer with fine mesh and rinse well, shaking the seeds gently to remove any remaining pulp and seed coatings.

5. Dump the seeds onto wax paper. Poke at the seeds with a toothpick or other clean utensil to separate them. Remove any dark seeds that don’t look right. They are not viable. Let the seeds air dry on the wax paper in a protected place for about a week.

6. Store the completely dried seeds in an envelope until you are ready to use them.

Now comes the science question: Do tomato seeds really need this kind of abuse to germinate?

The only way to find out is to experiment. Collect seeds from some ripe tomatoes—two or three tomatoes will do. Ferment half of the batch using the directions above. Rinse the remaining half with water in a sieve (to remove any attached tomato pulp), and then dry them on wax paper without any other treatment. When you have dried all the seeds, use the same procedure from Eleven Experiments with Radish Seeds to measure and compare germination rates.

Since you’re curious and kind of into this now, see if you can figure out if there are other ways to remove the seed coating that result in equal or better germination success. Some seed savers skip the fermentation and instead clean their tomato seeds with a solution of Oxi Clean. You can add this treatment to your experiment by dividing your batch of tomato seeds into three parts for: untreated, fermented, and Oxi Clean treatments.

The Oxi Clean method goes like this:

- Put the tomato seeds in a measuring cup and add water to make 1 cup of liquid.

- Add 1 tablespoon Oxi Clean power to the mixture and stir to dissolve.

- Let the seeds soak for 30 minutes.

- Rinse thoroughly in a sieve and dry on wax paper, just as you would with the other treatments.

As you will see, the Oxi Clean method is faster and there is no offensive odor, but is it better for germination?

Note: if you Google information about this, you will find articles that discuss Oxiclean (one word) vs. Oxi Clean (two words). The two commercial products are made of different chemicals. The former is a liquid that contains sodium hypochlorite (chlorine bleach), the latter, promoted by Billy Mays, does not. For the purposes of this experiment, the less caustic, powdered Oxi Clean pictured in this blog post works perfectly well. Students should report the actual chemical names in the materials list, not just the product name. It’s just like using the scientific name of a plant instead of the common name—it’s more accurate and less confusing for someone who wants to replicate the experiment.

If you are ambitious, try a treatment of your own. After all, three tomatoes are going to give you a lot of seeds to test. My daughter tried soaking some of her seeds in vinegar. Perhaps regular dish soap or ordinary laundry detergent will remove the seed coating. Or you could try a cleaner that contains chlorine bleach. It’s up to you. Please remember to wear goggles and plastic or latex gloves while handling any chemicals because, like the tomato seeds, your eyes and hands may need a protective coating to escape harm.

I’d like to tell you what is going to happen, but then I would totally lose street cred and face ridicule from my science teacher peeps. One hint, though: be sure to measure the timing of germination as well as the number of seeds that germinate in each condition. If you want to know what happens, you’ll just have to cut open some tomatoes and try it yourself.

©2014 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org