What if the next plant conservation project wasn’t down the street, or in the neighboring county, or far away in the wilderness? What if it was right above your head, on your roof? In our increasingly urban world, making use of rooftop space might help conserve some of our precious biodiversity in and around cities.

Unfortunately, native prairie plants have lost most of their natural habitat. In fact, less than one-tenth of one percent of prairies remains in Illinois—pretty sad for a state whose motto is the “Prairie State.” As a Chicago native, I found this very alarming. I thought, “Is it possible to use spaces other than our local nature preserves to help prevent the extinction of some of these beautiful prairie plants?” With new legislation at the turn of the century that encouraged the construction of many green roofs in Chicago, it seemed like the perfect place to test a growing hypothesis I had: maybe some of the native prairie plants that were losing habitat elsewhere could thrive on green roofs.

This idea brought me to the graduate program in Plant Biology and Conservation, a joint degree program through Northwestern University and the Chicago Botanic Garden. Here, I am investigating the possibility that the engineered habitats of green roofs can be used to conserve native prairie plants and the pollinators that they support.

Since I began the program as a master’s degree student in 2009, I’ve learned a lot about how native plants and pollinators can be supported on green roofs. For my master’s thesis, I wanted to see if native wildflowers were visited by pollinators and if they were receiving enough high-quality pollen to makes seeds and reproduce. Good news! The nine native wildflower species I tested produced just as many seeds on roofs as they normally do on the ground, and these seeds are able to germinate, or grow into new plants.

Once I knew that pollinator-dependent plants should be able to reproduce on green roofs, I set out to learn how to intentionally design green roofs to mimic prairies for my doctoral research. I started by visiting about 20 short-grass prairies in the Chicago region to see which species lived together in habitats that are similar to green roofs. These short-grass prairies all had very shallow soil that drained quickly and next to no shade; the same conditions you’d find on a green roof.

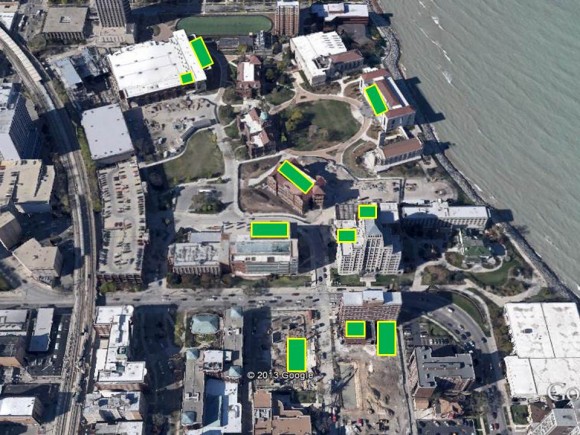

I’m now setting up experiments that test the ability of the short-grass prairie species to live together on green roofs. Some of these experiments involved using seeds as a cheap and fast way of getting native plants on the roof. Other experiments involved using small plant seedlings that may have a better chance of survival, although, as any gardener could tell you, are more expensive and labor intensive than planting seeds. I will continue to collect data on the survival and health of all these native plants at several locations, including the green roof on the Daniel F. and Ada L. Rice Plant Conservation Science Center at the Garden.

Ideally, I would continue to collect data on these experimental prairies to see how they develop over the next 50 years and learn how the plants were able to support native insects, such as pollinating bees and butterflies. But I didn’t want my Ph.D. to last 50 years so instead, I decided to collect the same type of data on green roofs that have already been around for a few decades. Because the technology is still relatively new in America, I had to go to Germany to collect this data, where the history of green roofs is much older. Last year, through a Fulbright and Germanistic Society of America Fellowship, I collected insects and data about the plant communities on several green roofs in and around Berlin and learned that green roofs can support very diverse plant and insect communities over time. We scientists are just starting to learn more about how green roofs are different from other urban gardens and parks, but it’s looking like they might be able to contribute to urban biodiversity conservation and support.

Now that I’m back in Chicago and have been awarded research grants from several institutions, I’m setting up a new experiment to learn about how pollinators move pollen from one green roof to another. I’ll be using a couple different prairie plants to measure “gene flow,” which basically describes how pollen moves between maternal and paternal plants. If I find that pollinators bring pollen from one roof to anther, this means that green roofs might be connected to the large urban habitat, rather than merely being isolated “islands in the sky,” as some people have suggested. If this is true, then green roofs could also help other plants in their surroundings—more pollinating green roof bees could mean more fruit yield for your nearby garden.

There are still many questions to be answered in this new field of plant science research. I’m very excited to be learning so much through the graduate program at the Garden and to be collaborating with innovative researchers both in Chicago and abroad. If you’re interested in keeping up with my monthly progress, please visit my research blog at the Phipps Conservatory Botany in Action Fellows’ page.

And if you haven’t already done so, I hope you’ll get a chance to visit the green roof at the Plant Science Center and see how beautiful plant conservation happening right over your head can be!

©2014 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org

A city with the motto “Urbs in Horto” (Latin for “City in a Garden”) deserves a signature fragrance: Tru Blooms Chicago debuts this fall as our fair city’s first-ever fine perfume. Today, the Chicago Botanic Garden held a preview of the fragrance and we personally enjoyed the lovely floral scent. Here’s why it’s a standout: it’s made with flowers grown in urban gardens throughout the Chicago area.

A city with the motto “Urbs in Horto” (Latin for “City in a Garden”) deserves a signature fragrance: Tru Blooms Chicago debuts this fall as our fair city’s first-ever fine perfume. Today, the Chicago Botanic Garden held a preview of the fragrance and we personally enjoyed the lovely floral scent. Here’s why it’s a standout: it’s made with flowers grown in urban gardens throughout the Chicago area.