I am often asked, “What can kids do to help the Earth?”

There is a standard litany of “Reduce, Reuse, Recycle” suggestions that almost everyone can tell you: recycle your garbage, turn the lights off when you leave a room, turn the water off while brushing your teeth, and so forth.

We’ve been saying these same things for decades. And while they’re great ideas, they’re things we should all be doing. It’s time to give kids a chance to do something bigger. During Climate Week this year, I am offering a different suggestion: Watch dandelions grow and participate in Project BudBurst.

We’ve been saying these same things for decades. And while they’re great ideas, they’re things we should all be doing. It’s time to give kids a chance to do something bigger. During Climate Week this year, I am offering a different suggestion: Watch dandelions grow and participate in Project BudBurst.

Project BudBurst is a citizen science program in which ordinary people (including kids 10 years old and up) contribute information about plant bloom times to a national database online. The extensive list of plants that kids can watch includes the common dandelion, which any 10-year-old can find and watch over time.

Why is this an important action project?

Scientists are monitoring plants as a way to detect and measure changes in the climate. Recording bloom times of dandelions and other plants over time across the country enables them to compare how plants are growing in different places at different times and in different years. These scientists can’t be everywhere watching every plant all the time, so your observations may be critical in helping them understand the effects of climate change on plants.

What to Do:

1. Open the Project Budburst website at budburst.org and register as a member. It’s free and easy. Click around the website and read the information that interests you.

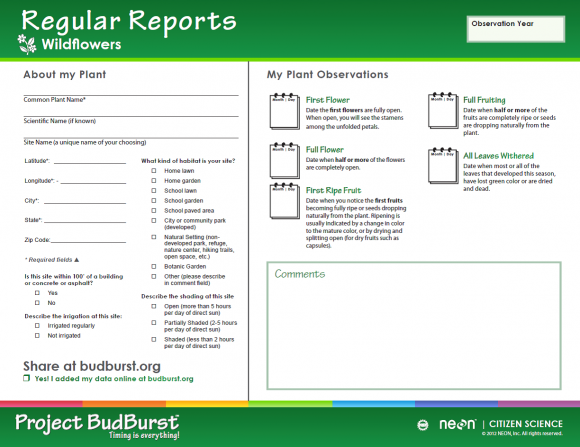

2. Go to the “Observing Plants” tab and print a Wildflower Regular Report form. Use this form to gather and record information about your dandelion.

3. Find a dandelion in your neighborhood, preferably one growing in a protected area, not likely to be mowed down or treated with weed killers, because you will want to watch this plant all year. It’s also best if you can learn to recognize it without any flowers, and that you start with a plant that has not bloomed yet.

4. Fill in the Wildflower Regular Report with information about the dandelion and its habitat.

Common Plant Name: Common dandelion

Scientific Name: Taraxacum officinale

Site Name: Give the area a name like “Green Family Backyard” or “Smart Elementary School Playground”

Latitude and Longitude: Use a GPS device to find the exact location of your dandelion. (Smartphones have free apps that can do this. Ask an adult for help if you need it.) Record the letters, numbers, and symbols exactly as shown on the GPS device. This is important because it will enable the website database to put your plant on a national map.

Answer the questions about the area around your plant. If you don’t understand a question, ask an adult to help you.

5. Now you’re ready to watch your dandelion. Visit it every day that you can. On the right side of the form, record information as you observe it.

- In the “First Flower” box, write the date you see the very first, fully open yellow flower on your dandelion.

- As the plant grows more flowers, record the date when it has three or more fully open flowers.

- Where it says “First Ripe Fruit,” it means the first time a fluffy, white ball of seeds is open. Resist the temptation to pick it and blow it. Remember, you are doing science for the planet now!

- For “Full Fruiting” record the date when there are three seedheads on this plant. It’s all right if the seeds have blown away. It may have new flowers at the same time.

- In the space at the bottom, you can write comments about things you notice. For example, you may see an insect on the flower, or notice how many days the puffball of seeds lasts. This is optional.

- Keep watching, and record the date that the plant looks like it is all finished for the year—no more flowers or puffballs, and the leaves look dead.

- When your plant has completed its life cycle, or it is covered in snow, log onto the BudBurst website and follow directions to add your information to the database.

Other Plants to Watch

You don’t have to watch dandelions. You can watch any of the other plants on the list, such as sunflower (Helianthus annuus) or Virginia bluebell (Mertensia virginica). You can also watch a tree or grass—but you will need to use a different form to record the information. Apple (Malus pumila), red maple (Acer rubrum), and eastern white pine (Pinus strobus) trees are easy to identify and interesting to watch. If you are an over-achiever, you can observe the butterfly milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa) bloom times and do citizen science research for monarchs at the same time! (The USDA Forest Service website provides information about that; click here for more information.)

For the past two springs, educators at the Chicago Botanic Garden have taught the fifth graders at Highcrest Middle School in nearby Wilmette how to do Project BudBurst in their school’s Prairie Garden. The students are now watching spiderwort, red columbine, yellow coneflower, and other native plants grow at their school. Some of these prairie plants may be more difficult to identify, but they provide even more valuable information about climate.

So while you are spending less time in the shower and you’re riding your bike instead of asking mom for a ride to your friend’s house, go watch some plants and help save the planet even more!

©2015 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org