Project Overview:

Shannon Still and Nick Jensen work on a project studying the impact of climate change on the distribution of rare plants in the western United States. The grant, funded through the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), examines the changes in projected species distributions between now and 2080. The goal of the research is to help BLM to make informed management decisions regarding rare plants. The research takes them to many exciting destinations as they search for rare plants in the west.

The silverleaf sunray (Enceliopsis argophylla), is a photogenic species in the Asteraceae, or sunflower, family. This rare plant grows in basal clumps of silver-colored, hairy leaves with flowers extended on long stalks, and the entire plant may reach 2 feet tall. The flowers nod with maturity.

The large yellow daisy flowers are 3 to 4 inches across when open. They are quite a sight and stand in stark contrast to the habitat. Due to the extreme habitat, silverleaf sunray offers one of the more striking photo opportunities as the plants grow from a barren landscape.

These gems are found in Clark County, Nevada, east of Las Vegas in the Lake Mead area. They are also found in Mohave County, Arizona, close to Lake Mead.

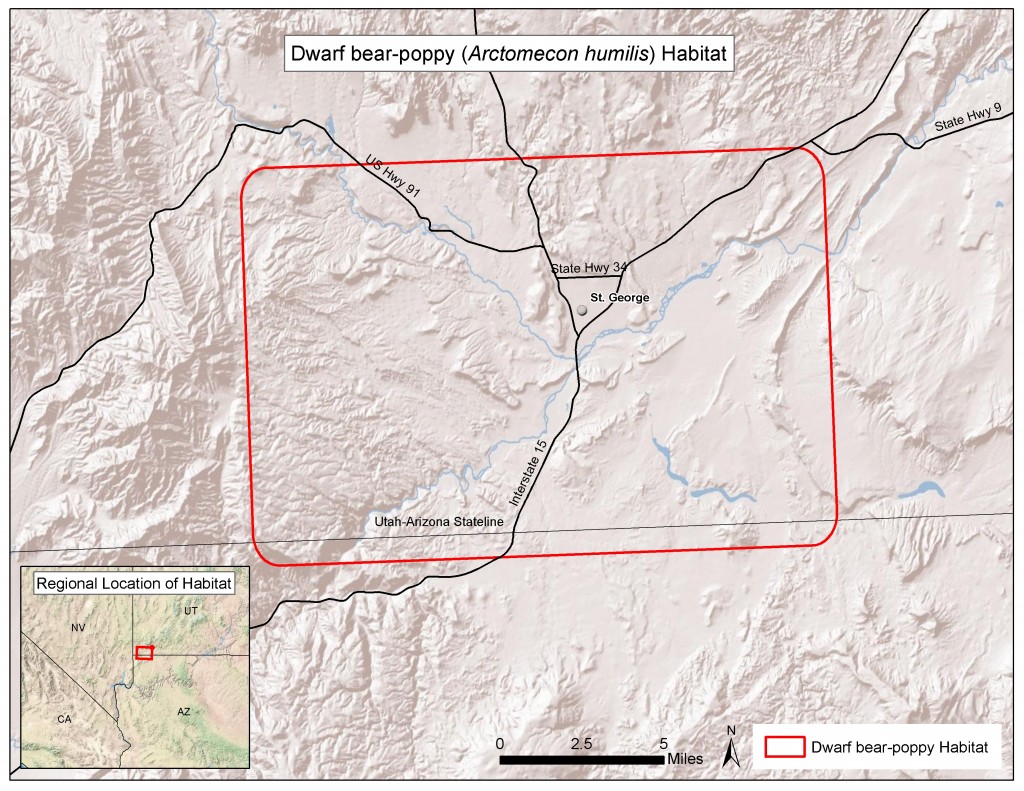

The habitat for the silverleaf sunray has been encroached by Lake Mead and is threatened by off-highway vehicle use to a minor extent. The habitat in which the sunray grows is easily damaged due to the fragile soil environment (see photos to left) in which the species lives. Much like the dwarf bear-poppy (Arctomecon humilis), the silverleaf sunray grows in a gypsum-rich soil that typically has a healthy soil crust. Damage to this crust can allow invasive plants to grow more easily.

The Bureau of Land Management lists the silverleaf sunray as a sensitive species in Nevada and the species was considered, but rejected, for protection under the Endangered Species Act. Around Lake Mead the silverleaf sunray grows with the golden bear-claw poppy or Las Vegas bear-poppy (Arctomecon californica), a federally listed species. So while the species is not federally listed, the habitat is often protected due to the proximity of other federally listed rare plants.

Silverleaf sunray is a striking plant that grows in close proximity to urban and recreation areas. If you are ever in the Las Vegas area, it is worth traveling the short distance to see these plants.

©2013 Chicago Botanic Garden and my.chicagobotanic.org